Worlds apart and in a different class

By Zhang Zhouxiang and Zhang Chunyan (China Daily Europe) Updated: 2015-08-16 11:56A TV documentary that followed a group of teachers from China as they imposed Chinese methods on a class of teenagers in a state school in England has reignited a longstanding debate

In the past few decades, China's rise to international prominence has prompted questions about the merits of the national education system, compared with those used in the West, and its contribution to the country's rapid development.

Critics claim that Chinese teachers are too strict and fail to engage the students, preferring instead to force-feed knowledge that will help the children pass exams but has little application in the real world. By contrast, supporters say, the system produces diligent, respectful children who will grow into resourceful, dedicated members of adult society.

|

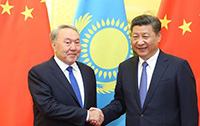

Elizabeth Truss, a member of the United Kingdom Parliament, talks with a student at a middle school in Shanghai in February. Truss led a British education delegation on visits to three schools to gain insights into the city's successful math education program. Xu Wanglin / For China Daily |

The debate has been reignited by a three-part BBC documentary Are Our Kids Tough Enough? Chinese School, which followed the travails of five Chinese teachers who spent a month working with 50 teenagers, ages 13 and 14, at Bohunt School in the southern English county of Hampshire.

The first episode, broadcast on Aug 4, showed the students performing synchronized morning exercises, participating in a long-distance running race, and learning how to exercise their eyes during breaks.

It was tough on the teachers, too, because they had to expend a great deal of energy and time to simply keep the noisy children quiet, leading one to complain that the classroom was always "chaotic". For their part, many of the students complained that the teachers were too strict, the lessons were boring, and they found it difficult to adapt to the new methods.

The difficulties were the result of cultural differences, according to Sun Jin, vice-professor of international and comparative education studies at Beijing Normal University. "Education serves social needs, and the system in each country simply produces graduates that fit that society. In one sense, both the Chinese and UK education systems are trying to cultivate things among students that their societies hold as virtues. While China has long pursued 'creativity' and 'critical thinking' in education, parents, teachers, and even company bosses still favor obedient students and employees," he says.

"People with innovative minds who are ready to defend their own opinions are more favored in Britain and Western countries as a whole; therefore their schools need to produce graduates with debating skills and rigorous minds," adds Sun, who also conducts educational research in Germany.

One of the teachers, Li Aiyun, who has taught at the Nanjing Foreign Language School for 25 years, says she insisted on strict discipline because talking during class is disrespectful. "British students favor thinking and self-expression instead of simply obeying authority, while Chinese students are more disciplined," Li says.

Zou Hailian, who taught math and headed the teachers group, attributed the lack of discipline to the large class sizes in the UK. "They (British students) are more used to group discussions. When it becomes a 50-person class like the ones we handled, talking is rather destructive," says Zou, who attempted to organize a "responsibility council" in which students took turns to be on duty "so that they know they are a group".

Richard Spencer, a Daily Telegraph journalist whose children have attended schools in China, wrote: "It (the program) is, perhaps, the first to expose so clearly the differences in our schools to those in China, whose well-disciplined pupils are now in some cases two to three years ahead of our own in measurable subjects like maths and science."

Social network users in both countries criticized the students for their "lack of discipline and respect for other people".

Writing on Weibo, a Chinese Twitter-like platform, user "Chu-hsi" commented: "Chinese classroom discipline is too strict to some degree. A free-style classroom means that students discuss academic issues in a better atmosphere, but also means eating, putting on makeup or doing whatever you like. The British students lack the most basic politeness, which is an issue of upbringing." The comment quickly attracted more than 2,000 "likes".

Many British netizens felt the same. One comment on Twitter that read "British education has gone soft. Teachers are abused and students have no discipline" gained 5,693 "likes" in next to no time.

Sarah Robertson, who identified herself as a BBC journalist writing in a personal capacity, tweeted that the documentary was "an insight into the sheer lack of respect some British teenagers have for teachers".

On a BBC debate, John Lester, 80, commented, "When I was at school during and after the war, we had discipline in schools."

Conversely, some commentators, such as columnist Simon Jenkins, were less impressed. "China's schools are testing factories. Why is Britain so keen to copy them?" Jenkins asked in his Guardian column.

"Chinese parents crave the British private schools being set up across China. Chinese students cram into US and British universities. They can see that a dragooned, mechanically competitive schooling is no path to creativity, challenge or happiness in the long run in a dynamic economy and a critical open society," he adds.

Neil Strowger, Bohunt School's head teacher, told China Daily the children had found the experience tough for a number of reasons. "Some of the students did find the Chinese way of teaching a challenge, and much of that was because the Chinese school day is longer than ours and the teaching approach is very different. We typically have seven or eight hour days, which meant that being taught for 12 hours came as a bit of a shock to some of the children," he says.

In an e-mail exchange with China Daily, the BBC commented: "This series was made to examine the significant differences between the Chinese and the British approaches to education. ... For several years some of the East Asian countries have beaten the UK on core subjects in international league tables, and we wanted to explore if their approach could be transferred to the UK classroom."

Cameras were set up to capture the experiment and to "give a true representation of how the students reacted to the Chinese teaching style". Bohunt School was chosen because it has "a good record of immersing their students in Mandarin teaching, which made it an ideal school for this series", the program maker says.

Despite the access given to the TV crew, some viewers, such as Sun Yunxiao, a researcher at the China Youth and Children Research Center in Beijing, felt some scenes were not consistent with the realities in China or the UK.

"The essence of Chinese-style education is to teach every student to discover his or her own strengths," Sun says. "We share that with the UK, but we didn't see that in the documentary."

"Tiangongzi", who has experience in both systems, echoed those sentiments. "They did the documentary in a British state school where lack of discipline is a common problem. Having attended a private school in the UK, I had to face three roll calls every day and faced suspension for any disciplinary violation; three times and the violator would have to quit," he wrote on Zhihu, a discussion forum, earning 946 "likes".

Wang Chengjun, a math teacher from Shanghai who attended a three-week teacher exchange and taught in a primary school in England in March, says British students are active in class, but are far from uncontrollable.

Strowger, who was quoted by The Times as saying the Chinese teaching style is about "delivering a monologue" and not about working with students, says, "The students who took part in the program did enjoy the experience and took a lot from it."

One major talking point occurred when disruptive students were punished by being made to stand in front of the class, a practice that was discontinued in UK schools decades ago.

"In China, we consider that as something to be disposed of, too. It's only used in schools with low standards. Those that have adopted modern values have long abandoned it," says Chu Zhaohui, a researcher at the National Institute of Education Sciences in Beijing.

According to the Chinese media, only two of the teachers - Zou and Li - were recruited directly from China, while the others are long-term UK residents who may not be familiar with current conditions in their home country.

"We are improving, but it may take a while for the idea of equality to become rooted in the minds of both teachers and students," Chu says.

Despite the various opinions and perceptions, one common point emerged: Cultural and country differences really matter, and the two countries can learn from each other's strong points to offset their own weaknesses.

"No one has a monopoly on what is right and wrong with teaching and learning", Anna Brunskill, who has taught in the UK but now works in Jerusalem, wrote in the Daily Telegraph. "Each country has its own unique educational culture that is a product of years, decades, if not centuries of experiment and practice, and which reflects the inherent values of its society."

Contact the writers through zhangchunyan@chinadaily.com.cn