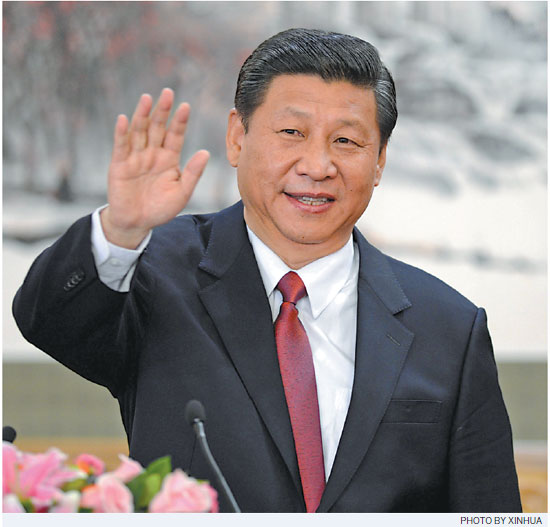

President Xi and his team have done a great job in areas where China's people had hoped to see progress

It's almost human nature that, when trying to understand a different political system, people either generalize or overcomplicate it, or sometimes both.

So it is with the many questions circulating in the overseas media about Xi Jinping - general secretary of the Communist Party of China since 2012, and the country's president since 2013.

Is he a "Mao-type" leader, with wayward political goals that must be attained at whatever cost, including steady development of the world's second-largest economy?

Externally, is he ready, again at whatever cost, to assert the kind of supremacy comparable only to imperialist powers in the past?

And internally, is he, with his soaring ambition, beginning to distance himself from the rest of China's leadership, and perhaps more dangerous, leading to a replay of the kind of "power struggle" that plagued Chinese politics from the 1950s through to the '70s?

These are not just personality questions; they are China questions. Because they derive from suspicion over the country's future: If it shows no sign of following the apparently benign, if not docile, pattern of change seen elsewhere in East Asia, how can it set a different course for a peaceful rise?

Yet the Xi phenomenon is by no means a puzzle. His arrival was China's answer to the most pressing question it faced three years ago.

When Western nations, led by the US, were on a spending spree driven by unbridled credit, the country kept its annual GDP growth at around 10 percent, based on massive exports of cheap manufactured goods. Statistically, China then was doing much better than China now, as today GDP growth has fallen to barely 7 percent and its exports have been in negative growth for some months.

But if overseas China watchers can recall the conversations they had with Chinese friends back then, they would be able to tell you what their friends were most concerned about: corruption, or more specifically, official corruption and the massive business interests that had been built by bureaucrats and bureaucracies at various levels.

Problems remained

Despite the exciting economic figures three years ago, many social problems remained to be tackled. Some problems were spreading, compounded by anachronistic rules and bureaucratic callousness: A migrant worker would have to make dozens of trips back to his hometown just to get a passport; an investor would need to spend a lot of money and time collecting many official approvals to start a small business; some officials were buying and trading their positions in secret.

It was a time when people with any sense of political responsibility were aspiring for change. They wanted something to be done to prevent bad officials from stealing the fruits of China's 30-odd years of market-oriented reforms.

For political scientists, it amounted to a question of how to prevent a leadership from losing its legitimacy and alienating the people who initially built it. And it was high time to find an answer.

President Xi Jinping was the answer, and a straightforward one at that. He and his team have so far done a great job in the areas citizens had hoped to see progress three years ago.

In an unprecedented twist in modern China's history, many high-ranking officials and army generals, with their extensive networks of political allies and business partners, have recently come under criminal investigation for the misuse of public funds. And many have pleaded guilty to criminal offenses when confronted with a massive collection of evidence.

So there is no reason to brand the ongoing anti-graft campaign as a power struggle or disagreement in policy orientation.

Attention to decency

Rounding up corrupt officials is not the key, however. The key is that the anti-graft campaign is making officials and all public service employees pay more attention to decency in their conduct and public image.

Rules and practices are being established to keep corruption at bay from the top down to the lowest local level thanks to the work of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, the Party's disciplinary body headed by financial specialist Wang Qishan.

Admittedly, problems still exist. No one - citizens or government policy - is looking at a paradise-on-Earth scenario. Corruption is a stubborn virus. But power, as its host, needs to be "shut in a cage of system checks", as Xi put it.

Citizens have been closely following the progress of the anti-graft campaign, and in online communities debates are lively and intense after each case is exposed.

Yes, there is cynicism, but few ordinary men and women would argue that the campaign has gone too far, or shouldn't have been so widespread. In contrast to the pessimism and nonchalance typical among those who take part in online debates, what is more commonly heard today is encouragement for leaders to do more.

The opinions shared on WeChat, the instant messaging app, go some way to reflecting the mass support that Xi's team has received. And it is support of a vitally important kind. First, it is based on a sentiment, and behind it a political awareness, that is widely shared by citizens, namely, the discontent with corruption and an aspiration for quick efforts to halt its spread. This is where Xi can most effectively build a national consensus and, through it, earn his team's credibility.

Observers may argue that the anti-graft campaign still has a long way to go in finding solid, lasting institutional solutions, but this end game is what Xi has promised to his comrades and the Chinese people.

Second, political unity will help China's economic transition in many ways. By its very nature, a major economic change can't make everyone or every company happy. Some industries that were flourishing several years ago will have to stop production and lay off workers. Saying a business model is no longer working is much easier than dispensing with it and building a replacement. It requires time. Economic officials have already warned that China's transition may take one to two decades to complete. During that process, political unity can guarantee social stability.

In addition, in a country with a large, centralized government, any economic transition inevitably involves many government initiatives, such as investment projects and social programs. Rooting out corruption can help the economy save a lot of resources and conquer the bureaucratic resistance to change.

How to manage political cost is an issue that can never be underestimated. There are ample instances in world history where politics, or a lack of institutional capabilities, ruined a country's chance to enjoy continued economic prosperity. Indeed, if not led by a decisive anti-graft campaign, one can hardly think of any practical starting point for China's economic transition.

Viewing China from this perspective, the country is by no means the mystery that some observers claim. It's simple: As citizens are alarmed about official corruption, and as the economy needs to do away with bureaucratic resistance to go forward, Xi and his leadership team have called themselves for duty. Three years after being sworn into office, this is the biggest issue they have been working on.

So much about Xi Jinping, president of China.

So much about the politics of China today.