Legal battle over Wang estate ends

By Ai Heping in New York | China Daily USA | Updated: 2018-02-27 16:05

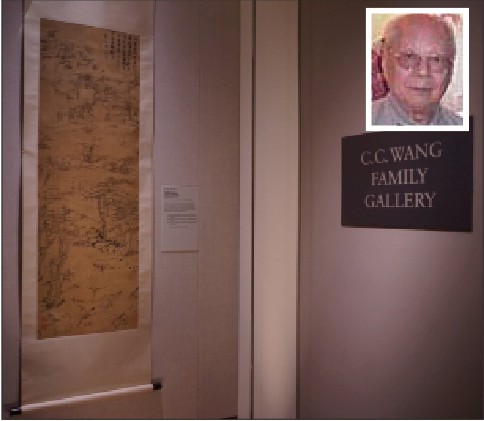

ZHANG RUINAN/ CHINA DAILY

The legal battle centered on a collection of classical Chinese paintings and scrolls that has been described as among the finest in the world. After 15 years, it ended in a New York City courtroom.

On Feb 15, New York County Surrogate Court Judge Rita Mella named Yien-Koo Wang King, executor of the estate of her father, C.C. Wang, the Chinese art collector who died at age 96 in 2003, and whose family roots go back to the Ming Dynasty.

Wang's paintings were once called the greatest collection of Chinese masters outside China and valued at more than $60 million. He sold centuries-old pieces for millions, including 60 that went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and are displayed on the museum's second floor in the C. C. Wang Family Gallery.

Before his death, Wang left some works to two of his children, his daughter Yien-Koo Wang King and his son Shou-Kung Wang. But following his death they filed lawsuits in state and federal courts accusing each other of looting Wang's collection and of deceit.

Last month's ruling dealt with the validity of a 2000 will that listed King as executor and a competing will drawn up shortly before Wang's death that named his son and his grandson, Andrew Wang, as executor and disinherited King. The grandson had acted as executor of the estate during those 15 years.

Last April, a jury found that because Wang suffered from dementia, he didn't have the capacity to execute the second will. Shou-Kung and Andrew were found to have used fraud and coercion to manipulate the art collector to remove King as his executor. Andrew was removed as executor.

According to the New York Law Journal, King claimed in court filings that her nephew had pilfered the family's collection for personal profit, selling nearly 100 works to himself at low prices and then selling them in China, which made him a fortune. She also claimed that he and his wife bought multimillion-dollar homes in the New York City area.

Shou-Kung and his son argued that it was King and her husband who diverted assets by hiding works in a warehouse in New York, transferring ownership of them to foreign corporations and selling them, according to the Law Journal.

King also claimed that the estate's value had plummeted to $2 million. The IRS has claimed the estate owes it $20 million.

Attorney Timothy Savitsky of the New York-based law firm Sam P. Israel, who is representing the 82-year-old King, told China Daily that being granted control over the estate was "the turn of the tide" because it allows King to pursue claims against Shou-Kung and Andrew Wang in state and federal court that they allegedly drained millions of dollars from her father's estate.

China Daily sought a comment from Carolyn Shields, the attorney for Shou-Kung and his son, but she could not be reached.

Among the missing works from Wang's collection that King is seeking to regain control of is an 11th century ink-on-scroll, Procession of Taoist Immortals. It is viewed in China as a national treasure, and some art experts have said it is worth tens of millions of dollars.

Wang was born near Suzhou in East China in 1907. After getting married at 21, he went to Shanghai, where he studied law because he said that his mother wanted him to follow a family tradition that began with Wang Ao, a Ming Dynasty prime minister 14 generations ago.

The prime minister was a prominent calligrapher, and his works sparked Wang's interest in art. He used his law degree for only two years. "I hated it," Wang told The Wall Street Journal in an article published in 1997. "I like everything beautiful and peaceful. I don't want to fight with people."

Wang came to the US in 1949 with his wife and his two youngest daughters, Hsien-chen Wang Chang and Yien-koo Wang King. He left behind his son so that he could take care of Wang's aging mother. The son made it to New York in 1979 with his family.

In Manhattan, Wang took courses at the Art Students League, taught art, consulted at Sotheby's auction house and dealt in art and real estate. By the end of the 1990s, Wang was an accomplished artist, producing art that ranged from classical Chinese landscapes to abstracts based on calligraphy.

In an interview with eChinaArt.com in August 2000, Wang was asked his views on reform in traditional Chinese painting:

"In any genre, most artists would 'sing the same old tune' (referring to Chinese opera), the more the old tune played, the less the people who are willing to hear it.

"The general public has a high tolerance for accepting something new," he said. "Many artists in China refuse to release the grasp on tradition that is a constraint on them developing. As for me, I like to 'sing new tune'. I have to create a style of my own, where I can say 'that's me.'"