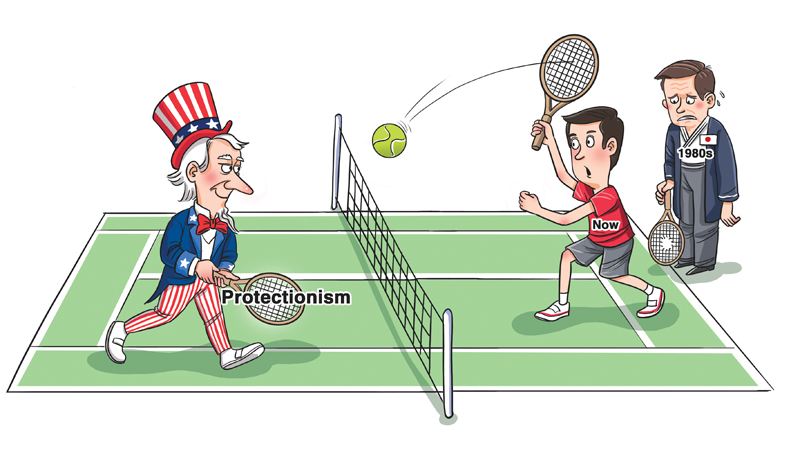

Sino-US trade war won't go the Japan way

By Alicia Garcia Herrero/Kohei Iwahara | China Daily | Updated: 2019-06-13 06:57

The United States has been criticizing China for its "unfair" trade practices and currency "manipulation", allegations that are strikingly similar to the ones the US labeled against Japan in the 1980s and 1990s, leading to the US-Japan trade dispute. The US criticized Japan for its large current account surplus, which resulted in long, intense trade negotiations between the two countries, and a broad range of economic policies to reduce what the US considered was Japan's excessive savings.

In hindsight, the US managed to contain Japan's rising growth momentum. Which gives rise to an important question: Will China meet a fate similar to the one that befell Japan in the last century because of the US-China trade war? Our answer is a definite "no".

Japan and China have challenged US hegemony at very different stages of their economic development. Japan faced US pressure when it was close to its economic peak with a rising aging population and stagnant labor productivity. But China's per capita GDP is still small compared with the US' and its population is much younger.

Furthermore, China's labor productivity has been improving rapidly on the back of larger investments in manufacturing and infrastructure. While still at an early stage of economic development, China's economic size is considerably larger than Japan's at its peak, and accounts for a significantly larger share of exports worldwide. Therefore, as China continues to climb up the technology ladder, its influence in the global economy is expected to increase, further challenging the US.

In light of the above facts, the outcome of the US-China trade war could be quite different from that of the US-Japan trade war, not to mention that China is less dependent on the US than Japan was, both politically and economically.

Arguably, Japan was an easy target for the US. Since the end of World War II, Japan has been both politically and economically dependent on the US, and therefore has limited bargaining power to counteract the US. But by being less dependent on the US, China is in a better position to resist US pressure to adjust its economic policies.

The massive appreciation of the yen and Japan's lax monetary policy helped increase the demand for more imports from the US. But we don't expect China to follow Japan's "forced" exchange rate and monetary policy, as a strong yuan could be the nail in the coffin for China's structurally weaker exports and rising wages. Moreover, while strong domestic demand could increase imports from the US, excessive policy measures to stimulate growth could lead to an overly lax monetary policy, potentially feeding an asset price bubble (as experienced by Japan), easily aggravated by China's aging population in major cities.

Another factor that harmed the Japanese economy was Japan downplaying its strong industrial policy, and accepting an increase in US semiconductor imports, which effectively reduced the competitiveness of Japan's own semiconductor industry. Similar lessons can be learned from Japan's auto industry. Since the Chinese government has more control over its economy than the Japanese government, the US administration could become more demanding of China.

Government intervention in the economy is a double-edged sword, as the US-Japan trade war showed. Although government intervention can support the development of strategic sectors, such as semiconductors, numerical import targets could reduce a county's competitiveness, as proven by the dismal fate of Japan's semiconductor sector after the US-Japan Semiconductor Agreement in 1986. While the private sector could respond to the crisis more effectively, as the Japanese auto companies did by increasing their investments in the US, state ownership could make adapting to a changing economic environment very difficult for many companies.

All in all, since China is relatively less dependent on the US, it is in a better position than Japan to resist changing its economic policies to meet the US' demand, thereby avoiding Japan's dismal economic fate. But while the government can support strategically important sectors to win a bigger global market share, it should avoid accepting numerical import targets, because they effectively reduced the competitiveness of Japanese semiconductor companies.

Since China is at an earlier stage of economic development than Japan, it is expected to challenge the US hegemony for an extended period of time. But that also means the US-China trade war could last longer than the US-Japan trade war.

With China's growth prospects still relatively solid-it could soon overtake the US economy in size and, unlike Japan, it does not depend on the US militarily-China will likely resist the US pressure to settle the trade disputes on its own terms. Which also means that any deal will only be temporary, as the US will not be able to contain China as easily as it contained Japan.

source:chinausfocus.com

Alicia Garcia Herrero is a senior fellow at Brussels-based Bruegel, and Kohei Iwahara is an economist based in Tokyo.

The views don't necessarily represent that of China Daily.