70 Mulberry Street: more than a building

By ZHAO XU in New York | China Daily Global | Updated: 2020-02-08 03:03

The Museum of Chinese in America in New York is optimistic about archives kept at a storied building hit by fire in Chinatown

One night in 1980, at around 9 o'clock, Charlie Lai, together with his friend Jack Tchen, was sweating to "physically build" the office space for what's known today as the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA).

Suddenly the phone rang, and the person on the other side of the line alerted Lai that a store in Chinatown was renovating and they were "throwing things out".

"Ten minutes later, we were there, standing on top of a big dumpster and picking voraciously, gradually reducing it to a much smaller mound," recalled Lai during a recent interview with China Daily. "It was two men's Gold Rush, the only difference being that those things are more precious than gold – they are our community's history."

They then walked all their new finds back to their place on East Broadway – a former clothing store the two had torn apart with their own hands in the hope of converting it to a permanent home for what they had been accumulating and hoarding.

For the past two weeks, the organization that Lai and Tchen co-founded has been making headlines, for the most feared reason. A fire that started on the fourth floor of a five-story Chinatown building around 8:45 pm on Jan 23 was at one time thought to have completely undone four decades of effort by the founders and their followers.

But it was not the fire but the gallons upon gallons of water pumped into the building in the initial 24 hours after the incident that posed the biggest threat to the 85,000 items housed in MOCA's Collections and Research Center on the second floor of the building, at 70 Mulberry Street in Manhattan.

On the morning of Jan 29, after an agonizing weeklong wait, 200 boxes were taken out of the ravaged site, with the overwhelming majority of them "in pretty good shape", said the museum president, Nancy Yao Maasbach.

While at least 25 boxes have been sent to Allentown, Pennsylvania, where they will be stabilized and freeze-dried (a process that involves freezing materials and then vacuum drying them so that the delicate fibers of the documents won't be broken up), the rest of the boxes are at the museum's gallery-cum-office on Centre Street, where they are being taken care of.

The latest development: MOCA has recovered one-third of its total collection and is awaiting word from city officials as to when retrieval of the remaining two-thirds of the collection from 70 Mulberry can begin.

For everyone who has gone from "we've lost everything" to "we are optimistic", the past two weeks represent an emotional roller coaster. This is truer for Lai than it could have been for most other people, not only because of the many nights spent prowling the streets in Chinatown and elsewhere in New York, for things rendered "worthless" by the closure of a Chinese laundry business or the passing of a senior, whom the land of America once beckoned with hope.

"Why is this so important? Because it took us a lot of effort to gain the trust from our community members so that they would go back home, rummage through their own stuff to add to this collective story of Chinese Americans in New York," he said.

In the early days, very often people being approached found the idea of preserving their memories strange. "We are lonely workers and we don't have any money. You should be talking to those famous people, not us!" – they would say.

"I told them that their stories were more important than those of the rich and the famous, that they were pioneers to whom I feel deeply indebted," said the Princeton-educated 65-year-old. "They needed to hear that before they could make very conscious decisions to share things – the only picture of someone's baby son for example – with the museum whose door they never thought about entering."

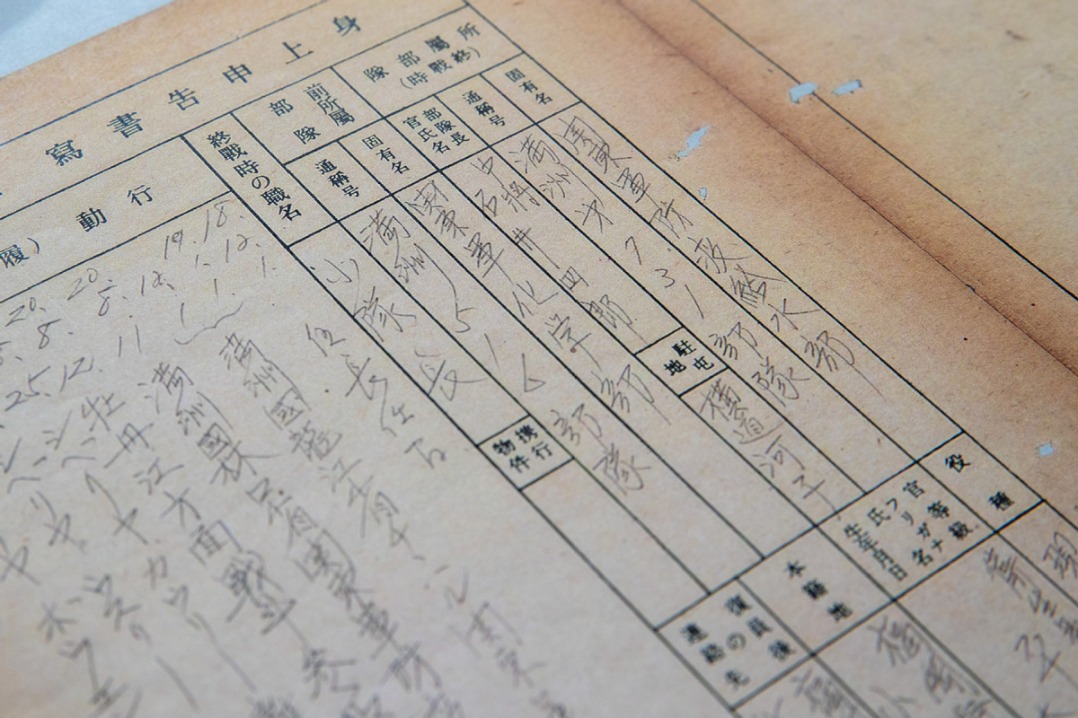

The resulting archive, amassed tirelessly by two generations of MOCA people, consists of numerous documents, photos and memorabilia, along with traditional Chinese festival and opera costumes as well as countless hours of oral history recordings.

Some items are evocative: a collection of about 100 pieces of paper sculpture made by Chinese immigrants while they were being held up in a prison facility in Pennsylvania in the 1990s; mind-revealing letters written home by "lonely workers" who had endured some of the most blatant forms of racism this country has ever seen.

The first immigration law that excluded an entire ethnic group — the Chinese Exclusion Act — barred almost all Chinese from entering the US except for scholars, merchants and diplomats. It was enacted in 1882 and was only symbolically repealed in 1943, when the quota was increased from zero to 105.

"Men who had come hoping to bring their families someday later found themselves stranded in a foreign land, members of a bachelor society that, despite their hard labor, barely earned a footnote in the annals of American history," said Lai. "MOCA is our belated tribute to these men without whom I wouldn't even have the luxury of building a museum."

In 1892, the Chinese Exclusion Act was renewed 10 years after it was first signed into law by a US president. Also in that year, a five-story red-brick and brownstone building was erected on 70 Mulberry Street to house Public School 23, in what is now the center of Manhattan's Chinatown.

"But that place wasn't exactly a Chinatown back then," said Corky Lee, a photographer who has spent the past half century documenting the lives of Chinese Americans, their pain and pathos, struggle and survival.

"At first there were the Italians and the Irish, and few Chinese given the impact of the Exclusion Act," said Lee, who had his solo exhibition at MOCA in the early 1980s. "In those days, every Chinese in America had to carry personal identification – failing to do so may mean a deportation. And the only other individuals who were required to do that were convicted criminals and prostitutes."

In 1905, the New-York Tribune called PS 23 "the school of 29 nationalities". In 1906, it was so successful that it became the first school visited by a cohort of 500 teachers, sent by Britain's head of education, to study the American school system.

But if you listen to Lai, up until the 1960s, attending this elementary school could be hard for Chinese children because "you are really the minority, and there was a lot of racism".

Born in 1954, New York City Councilwoman Margaret Chin was among those who went to the school, after she moved to New York with her family from Hong Kong.

The family hailed from South China's Guangdong province, source for the overwhelming majority of Chinese immigrants who came to the US over the past 200 years.

"I was just devastated (upon hearing the news of the fire)," said Chin, a strong supporter of all five organizations housed inside the building, including the Chen Dance Center, which moved in 1980. Five years earlier in 1975, PS 23 was decommissioned due to a local population decline and the construction of a new school nearby.

Calling the building "graceful", Dian Dong, together with his Shanghai-born, Julliard-educated husband H.T. Chen, founded the center in 1979.

A fifth-generation Chinese, Dong had an uncle who fought in World War II as a US Air Force bomber pilot and died heroically while on duty, and a grandfather who came in 1864, at the height of the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, built primarily by Chinese and Irish laborers between 1862 and 1869 to link the United States from east to west.

in pink to her right is Margaret Chin, the New York City Councilwoman. PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY

"The location of the building, in the center of Chinatown, is symbolic for us. As the only Chinese modern dance company in Manhattan Chinatown, we allow us to be inspired again and again by the unique and irreplaceable Chinese-American experiences," she said.

Inspirations came equally from small Chinese communities in Mississippi, caught between the opposing white and black societies, and from the Chinese workers in the sewing factories in New York, some of whom came from California, where gold was discovered in 1848.

The California Gold Rush saw the first big wave of Chinese immigrants, many who came across the ocean on boats with no sails. Later, the majority of them worked on the Transcontinental Railroad, joined by others recruited from South China, mainly Guangdong province. (To learn more, MOCA has an ongoing exhibition at its galleries on Center Street titled The Chinese Helped Build the Railroad – The Railroad Helped Build America.)

At the completion of the railroad, the Chinese laborers had to look elsewhere for work and were forced to move eastward by rampant racism in California and other places.

Many of those who ended up in New York worked in restaurant kitchens. And it was typical for a Chinese immigrant family to open a hand laundry business in the city – it required no English and the family could live within the laundry; its coal-burning stove used for heating the iron also provided much needed warmth during winter times.

One of those stoves is in MOCA's ongoing exhibition Gathering: Collecting & Documenting Chinese American History at Centre Street, which brings together 29 organizations in the field, including one from Canada.

Another much earlier tribute came in 1984, when the museum put on an exhibition titled Eight Pound Livelihood, "eight pound" referring to the weight of an iron. The exhibition was held inside the Chinatown Senior Center, which since 1979 has occupied the ground floor at 70 Mulberry.

"We wanted to bring the show to those seniors, because it was about their lives, and it was they who contributed to our oral history project," said Lai.

MOCA moved into 70 Mulberry one year later, in 1985, sharing the second floor with the Chen Dance Center and the United East Athletics Association (UEAA). Established in 1976, UEAA offers constructive sports programs to mostly immigrant youths from the Chinatown area, trying to reduce the "growing pains" that could have been acerbated as they plunged headlong into a whole new environment, often as ill-prepared as the adults, especially in early days.

The rest of the building – the entire third, fourth and fifth floors, belongs to the Chinatown Manpower (CMP), a nonprofit that moved in toward the end of the 1970s and has been dedicated to promoting "self-sufficiency and career advancement", mainly among Chinese immigrants whose skills were not easily transferrable in their newly adopted home.

By the mid-1980s, the former school building at 70 Mulberry had become a vibrant hub, "a pillar to the Chinatown community", to quote New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio in a recent tweet.

Lai, who left MOCA in 1989, served as the director of CMP in 1995 and 1996, sitting a couple of floors above his former office. (He returned to the museum in 2003 and didn't leave until 2009, after MOCA moved to its current location on Centre Street. The new space was designed for MOCA by Maya Lin, a Yale graduate who also designed the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington and whose famous aunt Lin Huiyin was thought to be modern China's first female architect. )

"I came to the US with my parents and five siblings in 1965, the year when the quota of Chinese immigrants allowed to legally enter the country was raised from 105 to 10,000. That was really the beginning of a bustling Manhattan Chinatown, one that hasn't stopped changing," Lai said.

He said the decision to join CMP was influenced by his mother, whom Lai described as "the last person on the production line at a local garment factory, putting tags on the clothes, because she didn't have any other skills".

"In her life, she never walked alone out of the few blocks of Chinatown. That was her world and her boundary. Why? Because she didn't understand English," said Lai. "In that, she was not alone."

Committed to coming back to Chinatown ever since entering university, Lai was dedicated to letting his fellow Chinese Americans go outside "the invisible four walls of Chinatown", so that they could have "a deeper access to a broader American economy".

Training courses provided by CMP included English, accounting and computer skills. Over the years, tens of thousands of people have been trained, including the mother of Yao Maasbach, former executive director of the Yale-China Association who became MOCA president in 2015.

According to Yao Maasbach, the Chen Dance Center is where her daughter took her hip-hop classes last summer. It's also where three generations of a family would go for a modern dance rendition of their own and their ancestors' happiness and sadness.

All of this happened inside 70 Mulberry, an address that Herb Tam, the MOCA curator and director of exhibitions, first visited when he came to New York from San Francisco to study art in the early 2000s.

"At the time, it was a museum, an office space and a storage and a research center, with boxes of archives stacked on people's desks," recalled Tam, who came to the US with his parents in 1974, when he was 2 months old.

"Over the past decade, so much has been done in conserving, cataloging and digitalizing all the materials we have. Of the 85,000 items, 35,000 have been digitized and are accessible online for researchers worldwide.

But for a history buff who has paid his pilgrimage to 70 Mulberry, nothing beats the experience of following an archivist into one of the rooms and watching with silent glee as the staff pulls out a box and opens it.

"Even before we moved to Centre Street in 2009, I knew that the museum would soon outgrow its new location and that we would move to other places in due time, but this place on 70 Mulberry will always be there – we'll always keep our roots in the Chinatown," said Tam.

The fire that ripped through the building burned the roof off but didn't do much damage to its structure. At a news conference last Wednesday, Lisette Camilo, commissioner of the Department of Citywide Administrative Services, said, "The mayor's office is very committed to ensuring that this building is brought back, and services that are provided to this community will continue in this building."

In 1975, after PS 23 was decommissioned, the building was vacant for nearly two years. It started to look deserted before being given by the city for use by the various organizations, each with its own link to the local Chinese community.

"Back then, it took all these organizations to bring the building back," said Lai. "Now, the fire, devastating as it is, may in its aftermath prompt a complete overhaul and upgrade of the building, which is long overdue. In my mind's eye, I've already started to see how it will look, with a restored façade that appears the same it was, and an inside that's more modern and holds more potential for its tenants.

"It's time for a rebirth," he said.

Belinda Robinson in New York contributed to this story.