A tale of Chang'e 5 probe: Fly me high through the starry skies

By Fu Tianlin | chinadaily.com.cn | Updated: 2020-12-21 11:11

With lunar samples collected by China's Chang'e 5 probe now kept at a top laboratory in Beijing and expected to be unsealed, my thoughts have settled on the meaning of China's latest space expedition.

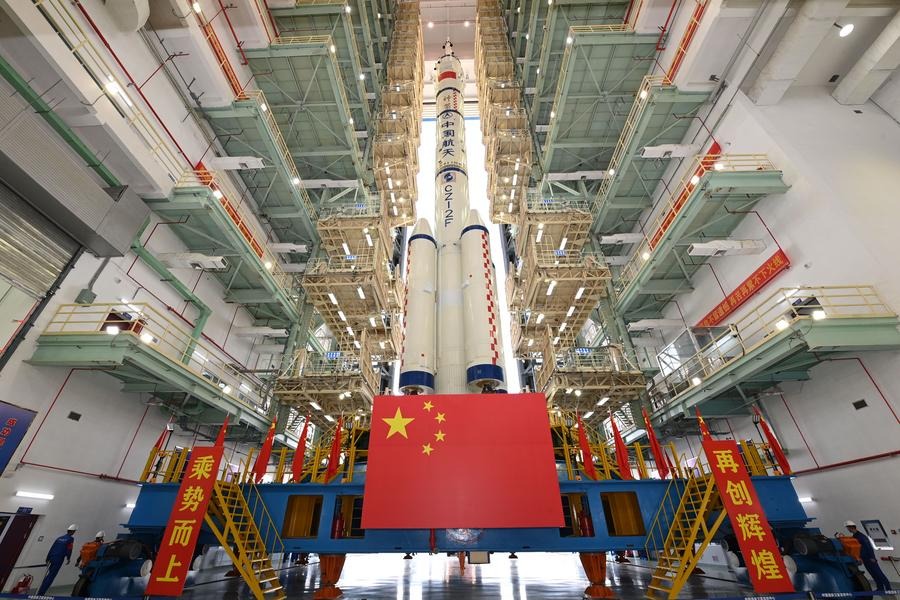

As the Long March-5 rocket carrying Chang'e 5 blasted off on November 24 and pierced through the night sky, it not only lit it up, but also rekindled my passion for astronomy.

Seventeen years ago, I sat on the couch with my family members, watching live TV broadcast of the launch of Shenzhou 5 space module. Time has not eroded my passion for this centuries-old subject.

It was the first time that China had tried to send an astronaut into outer space. Nobody knew what would happen. When the countdown began, nervousness pervaded our family home and I remember falling into silence.

The launch was a huge success and sent a clear message of peace and love when Yang Liwei, the Chinese taikonaut behind the historic manned space mission, held flags of the United Nations and China, expressing hope that we can make use of outer space peacefully, for the benefit of the mankind.

Human curiosity about astronomy has lasted centuries. Through our exploration of the vast universe, we gradually escape from anthropocentrism, the ancient Greek belief that man is at the heart of the cosmos.

Our path to outer space, however, is littered with struggles and sacrifices of those who went before.

In the Middle Ages, the Roman Catholic Church stood in the way of science and labeled heliocentrism as a heresy. Galilei, the Italian physicist, was incarcerated for the last few years of his life due to his support for heliocentrism.

In China, the imperial court also forbade people from studying astronomy. In the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), a Chinese stargazer named Wan Hu was so obsessed by the celestial bodies that he hatched a scheme to get himself closer to them.

Around a time believed to be in the 1500s, he made a "spacecraft" out of a sturdy chair, two kites and 47 of the largest gunpowder-filled rockets he could buy.

Despite his servants' best efforts to talk him out of this foolhardy adventure, he chose to take the risk nonetheless. Wan even apocryphally said that flying had been China's dream for thousands of years and he was willing to shed his blood over this cause.

Wan did sacrifice himself. After an explosion, both the "spacecraft" and he were blown to pieces.

Four centuries later, people finally realized Wan Hu's dream. Yuri Gagarin from the Soviet Union was the first human to travel in space in 1961 and circle the Earth for a little more than one orbit.

He was followed by Neil Armstrong, an American, who walked on the Moon in 1969 and famously said "that's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind”.

Past successes of space missions shouldn't lull mankind into complacency. Tragedies such as the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986 and the Columbia disaster in 2003 serve to remind us of how much more we have yet to know about the dangers of the universe.

Danger hides in its darkness and catches us by surprise. Behind the facade of serenity, the universe is alluringly dangerous with its black holes, mythical hostile aliens and radiation. In front of the multi-billion-year-old universe, man isn't even remotely comparable to a newborn.

In recent years, a string of science fictions and movies of this genre highlighted humans' limited knowledge about the universe. In the movie Gravity, astronauts are gobbled up by the universe all of a sudden. In the novel The Dark Forest, author Liu Cixin describes the universe as a dark forest, in which every civilization is left with only two cruel options: keep silent or make sounds and be eliminated.

Despite these apocalyptic views, man's exploration of outer space continues, driven not just by the quest to exploit their discoveries, or as some sensational newspaper headlines put it, to weaponize and colonize outer space, but by a belief that space missions are about better finding out who we are and who we should become.

I believe that when future humans soar out of the Earth, whether on a spaceship or aboard Elon Musk's Space X rocket, and look back on our current issues, they might sneer at their predecessors for agonizing over a series of trivial matters.

Problems like national conflicts, trade disputes and terrorism that we believe are intractable might pale in comparison to the many great unknowns about universe several years from now.

It's true that political rivalries and conflicting interests are likely to divide humans for the time being, but who knows if the future generations will live together in a global village as envisioned by Canadian philosopher Herbert Marshall McLuhan, as they stand united in a bid to unravel the mysteries of the universe?

The universe, a four-dimensional space, never fails to attract three-dimensional creatures with its beauty and infiniteness.

Back in the summer of 2003, my mother brought me to her hometown, a village near northern China's city of Baoding. Born and raised in a city, it was my first time to be in the countryside.

In the family courtyard, I sat on a portable stool, waved the fan, and gazed skyward at the starry night. The sublime beauty of the Milky Way sparked a five-year-old's passion for astronomy. I believe in ancient times, even Socrates, a man known for being eloquent, would also be in awe and speechless when he first saw the starry night. Likewise, his posterity continued to fall under its spell.

Welcome home, Chang'e 5.

The author is a master's student studying at Fudan University's School of Journalism.

The opinions expressed here are those of the writer and do not necessarily represent the views of China Daily and China Daily website.

If you have a specific expertise and would like to contribute to China Daily, please contact us at opinion@chinadaily.com.cn, and comment@chinadaily.com.cn.