What explains US antagonism toward China?

By Zhang Jun | China Daily | Updated: 2021-06-07 08:20

The US Senate Foreign Relations Committee has officially backed the Strategic Competition Act of 2021, which labels China a strategic competitor in a number of areas, including trade, technology and security. Given the bipartisan support the bill enjoys-exceedingly rare in the United States nowadays-the Congress will most likely pass it, and President Joe Biden will sign it. With that, the US' antagonism toward China would effectively become enshrined in US law.

The Strategic Competition Act purports to highlight supposed "malign behaviors" in which China engages to attain an "unfair economic advantage" and the "deference" of other countries to "its political and strategic objectives". In truth, the bill says a lot more about the US itself-little of it flattering-than it does about China.

The US used to have a sanguine view of China's economic development, recognizing the lucrative opportunities that it represented. Even after China's emergence as a political and economic powerhouse, successive US administrations generally regarded China as a strategic partner, rather than a competitor. But, in the last few years, the view that China is a strategic rival has taken over the US political mainstream, with leaders largely choosing confrontation over cooperation. Two features of this shift stand out: the fast pace at which it happened, and the extent to which Americans, and their leaders, have united behind it.

Ironically, the problem is partly rooted in extreme ideological polarization, which has impeded US political leaders' ability to govern effectively and minimize the social costs of structural transformation in the age of economic globalization and digitalization. These failures fueled popular frustration and social tensions, creating fertile ground for previous president Donald Trump's populist "America first" campaign.

Vilification of China-which, unlike the US, prudently managed the risks of globalization to minimize the costs of structural change-was central to Trump's electoral appeal. Perhaps it is also the starkest feature of the Trump doctrine surviving the transition to Biden's administration.

The anti-China narrative has thus restored some common ground to US politics. Unfortunately, Americans are agreeing on an idea that will do them far more harm than good. What the US should be focusing on is how to benefit from globalization and technological progress, and manage the risks arising from associated structural disruptions. To that end, effective cooperation with China, together with a broader embrace of free trade and economic openness, would be hugely helpful.

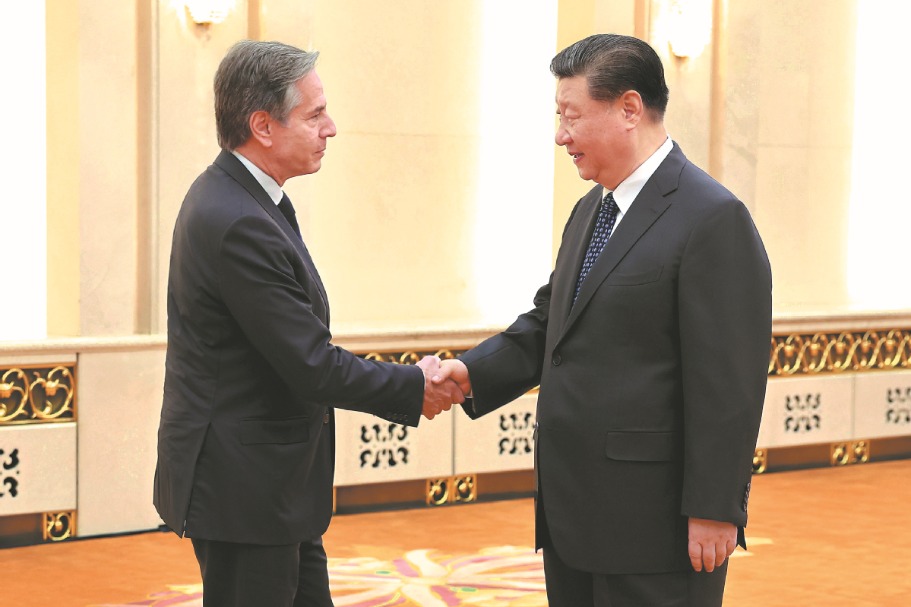

In fact, according to former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger, who spoke at a special session of the China Development Forum in Beijing in March, a positive, cooperative bilateral relationship is essential to global peace and prosperity. And no American alive today is better qualified to assess Sino-US relations than Kissinger, whose secret mission to Beijing 50 years ago led to the restoration of diplomatic ties. In his remarks, Kissinger acknowledged how difficult it will be to build the Sino-US relationship the world needs, noting that the different cultures and histories of these two "great societies" naturally lead to differences of opinion. Modern technology, global communication, and economic globalization further complicate the ability to reach a consensus.

Kissinger is right to highlight modern technology as a key challenge. In the past, when dominant media organizations largely shaped the popular narrative, remaining relatively neutral was the most effective way to compete. With voters all sharing roughly the same facts, politicians' best bet was to appeal to the "median voter", rather than those on the extremes. (As Anthony Downs explained with his "median voter theorem"-inspired by the Hotelling model in economics-the outcome of majority voting is the median voter's preferred option.)

But modern technology has fragmented the media landscape and eroded the "gatekeeper" role of traditional news organizations. Inaccurate, misleading, or otherwise unreliable information can be disseminated among a huge audience instantly. Moreover, it can be targeted at those who are most likely to agree with it, and kept away from those who would disagree.

This has fueled a growing preference for "personalized" information-and transformed media's competitive strategies. In this environment, neutral reporting doesn't attract as much attention as inflammatory or ideologically driven reporting, especially if the latter is algorithmically targeted at those who are primed to embrace it. The media's role in establishing a common factual basis has thus increasingly gone by the wayside and, with it, the strategy of appealing to the median voter.

As US media embraced increasingly biased, targeted strategies, deep polarization became all but inevitable. This, together with US politicians' new incentives to appeal to the ideological extremes, has torn the fabric of American society, fueling instability and conflict, hampering leaders' ability to address urgent challenges, and undermining the US' global leadership position.

China has largely avoided this pitfall of modern technology, though not without cost and criticism, by controlling extreme online speech and limiting populist attacks on mainstream values. But it has not avoided the US' media-fueled ire. In a matter of just a few years, US-China relations have regressed significantly, and the global free trade system has been pushed to the brink of collapse.

As Kissinger made clear, the difficulty of restoring Sino-US relations should not deter leaders from trying. On the contrary, it demands that both sides make "ever more intensive efforts" to work together. For the US, however, that work must begin at home. The real threat to the US is not from a rising China, but from its inability to meet the challenges of modern technology.

Project Syndicate

The author is the dean of the School of Economics at Fudan University, and director of the China Center for Economic Studies, a Shanghai-based think tank.

The views don't necessarily reflect those of China Daily.