The vote that shook up the world

By ZHAO XU in New York | China Daily | Updated: 2021-11-20 08:07

For John Lee, Sept 22, 1971, was a day to remember. "It was all about the optimism of youth-young people pursuing what we believed to be right," Lee, now 72, says.

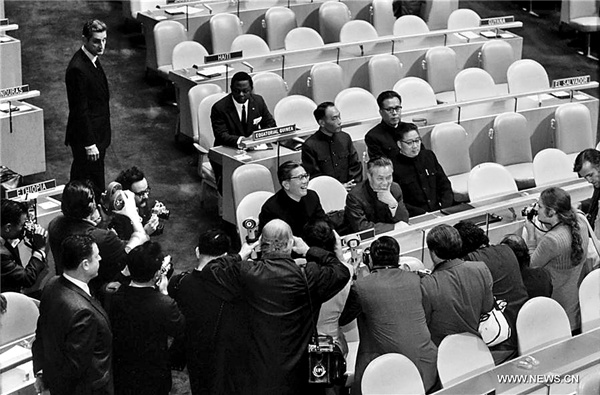

That day the 22-year-old and his elder brother Corky were among 900 people who marched in Manhattan, New York, near where United Nations headquarters is located, as-to quote a report carried by The New York Times dated Sept 19, 1971-"127 UN delegations are busily lobbying and being lobbied on the issues of whether Peking should be seated, whether Taipei should be expelled and whether such an expulsion would be an 'important question' and thus require a two-thirds vote instead of the usual majority".

A month later, on Oct 25, the 26th UN General Assembly rejected the "important question" resolution, a procedural maneuver successfully used by the United States in the 1960s to block Beijing's effort to seek representation in the UN. The assembly then proceeded to pass Resolution No. 2758 with an overwhelming majority: 76 votes for, 35 against and 17 abstentions.

"The General Assembly... decides to restore all its rights to the People's Republic of China and to recognize the representatives of its Government as the only legitimate representatives of China to the United Nations, to expel forthwith the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek from the place which they unlawfully occupy at the United Nations and in all the organizations related to it," the text of the resolution said.

Francis Plimpton, a US diplomat who was part of the US delegation to the UN in the 1960s, wrote: "The presence of Peking will strengthen the status of the UN as a ready made forum for multilateral diplomacy, a place where representatives can quietly negotiate among themselves without the disadvantages of trying to handle multifaceted problems by disparate bilateral contacts or by multiparty ad hoc conferences."

Lee, calling the UN adoption of the resolution a "breaking point", sees the demonstration as the harbinger of that historic moment.

"It was enlightening to see significant numbers of Chinese coming out in public in support of the PRC. It had been largely a private endeavor up to that point. I dare say that many who had been brought in by the KMT(Kuomintang) to march on their side were quite surprised to see us."

Between 1946 and 1949 the Chinese Communists, led by the Communist Party of China, were at war with the Nationalists, led by the Chinese Nationalist Party, or KMT. Despite strong backing from the US, the Nationalists, with Chiang Kaishek as the paramount leader, suffered a humiliating defeat before fleeing to Taiwan for a foothold there. On Oct 1, 1949, the People's Republic of China was born.

For the next 22 years, with what the Chinese government calls "the manipulation of the United States",Chiang Kai-shek continued to send his people to New York to represent China at the UN. This despite Beijing's ceaseless "struggle to restore China's lawful seat" and despite what Lee calls "the apparent absurdity of the arrangement", against which the brothers and their fellow pro-Beijing protesters had demonstrated.

"I remember seeing the KMT buses rounding the corner of 42nd Street and coming into our view from across the street," Lee says.

"What followed was a massive shouting match."

Fearing a physical clash, police, massing on side streets, asked Lee's group to stop where it was, a couple of blocks from its planned destination, the UN Plaza. Hugely disappointed, Lee, who had been acting as the group's liaison person with the police, found himself arguing fervently with an officer, watched on by the legion of camera-hauling international reporters.

"All the time I was thinking to myself: 'Dad's going to see this on TV tonight'," Lee says, referring to his late father, who watched the evening news religiously, and who had dropped by Lee's apartment that morning casually asking about his son's plans for the day.

The father came again a week after the demonstration. "'You know, there's a great deal of danger those supporters of the (Chinese) mainland undertook ... But what's right must be expressed.' That's what my father said, and he just left it at that," says Lee, who later studied law and went into practice on the West Coast.

"Everyone was watching," was how Charlie Lai, one of the founders of the Museum of Chinese in America in Manhattan, describes the mood of Manhattan Chinatown in the months before the UN resolution. "It's all about if you are not strong enough, they could ignore you."

Lai was also thinking about the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first immigration law in the US to exclude an entire ethnic group. Enacted in 1882, it barred almost all Chinese from entering the country except for scholars, merchants and diplomats. Although the law was revoked in 1943, it was not until 1965 that Chinese were finally allowed to come in relatively large numbers.

That was the year when Lai, 9, with his parents and five siblings, arrived in New York from Hong Kong, where the couple from southern China had previously sought refuge during Japan's invasion of China in the 1930s and 40s.