Corky Lee's brother recalls the famous photographer's activism

By BELINDA ROBINSON in New York | chinadaily.com.cn | Updated: 2024-09-20 11:13

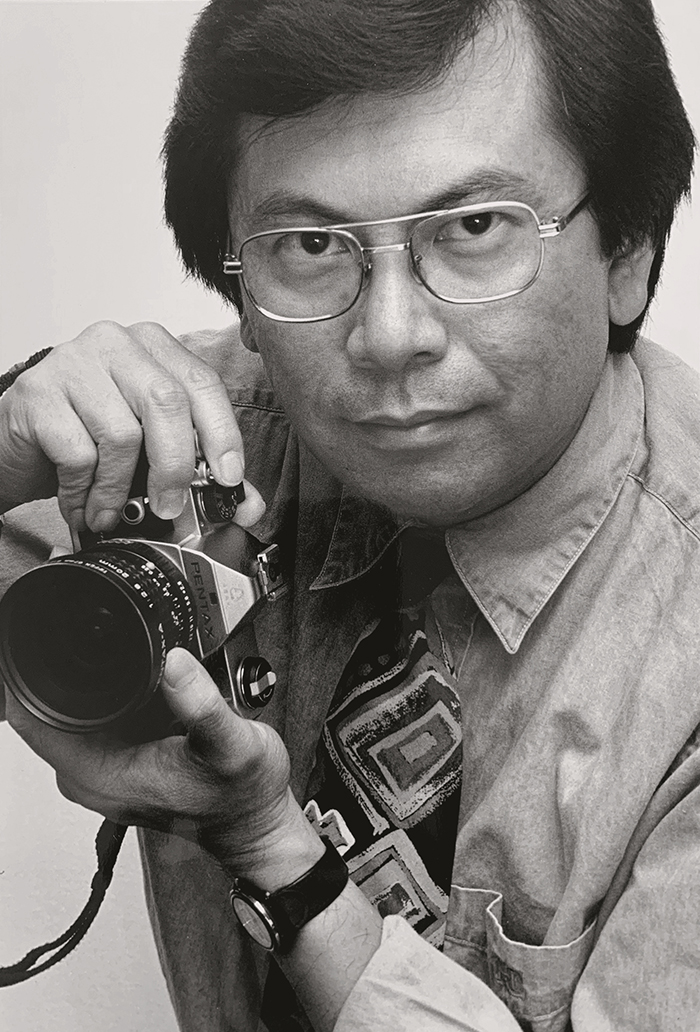

Through his camera lens, Corky Lee provided a window on the struggles and triumphs of Asian Americans for more than five decades.

But three years after the death of the preeminent Chinese American photojournalist, who died in January 2021 at age 73 of COVID-19 complications, he is sorely missed by his community, friends and family.

John Lee, Corky's younger brother, who lives in Southern California, reminisced fondly on all that his sibling achieved while remaining "humble" and "generous".

"Despite the accolades [Corky] received in the later years of his life and posthumously, his popularity and leadership grew from a unique combination of humility and generosity," John told China Daily. "One writer astutely observed [that he] helped generations of Asian Americans see themselves."

As the administrator and executor of Corky's estate, John, a lawyer and retired public defender, takes comfort in advancing his brother's legacy so that new generations can appreciate his incredible body of work.

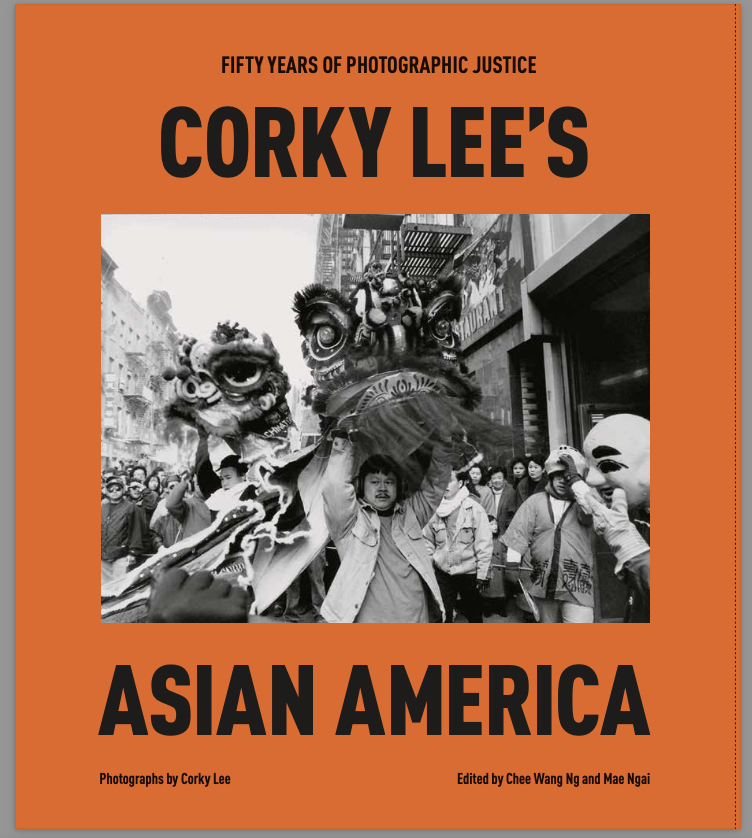

In the new posthumous book, Corky Lee's Asian America: 50 Years of Photographic Justice, more than 200 photos reflect the art and life story of the man dubbed the "undisputed, unofficial Asian American photographer laureate".

Born on Sept 5, 1947, in Hollis, Queens, New York, to mother Jung Ping Hung and father Lee Yin Chuck, Corky had three brothers, John, James and Richard, and an older sister, Fee. Their parents immigrated to the US from Taishan, in South China's Guangdong province.

Corky's given name at birth was "Lee Young Kok'', which foretold his destiny, as it means "praiseworthy of the nation" in Chinese. His US birth certificate recorded his name as "Lee Young Quoork'', because his father used the name Quoork when he arrived in the US in 1925, saying he was born in China to a person with US citizenship, as a way to avoid the restrictions of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

By 1960, the family and grandmother settled in Jamaica, Queens, New York, where they ran a laundry business and lived above it. All the boys were expected to pitch in and help. Their mother was a seamstress.

John recalled that while growing up, Corky's responsibilities were "much the same as those of other Chinese American baby boomers with immigrant parents''.

Corky came of age during the civil rights era in the 1960s when all minorities — African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian American and Pacific Islanders — fought for equal rights.

The family would often sit around the dinner table and discuss current events.

"It was a time of social and political ferment outside the family laundry. Our father, despite his lack of formal education, was a very astute observer and had a lifelong intellectual curiosity, which he successfully passed on to Corky," John said.

The soon-to-be photographer attended a New York City public school. He got his nickname Corky from a "white kid'' in the neighborhood while a student. He later attended Queens College, where he majored in history.

As he emerged from college, Corky was inspired by leaders like John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr, which ignited his own activism.

Lee Yin Chuck was a World War II military veteran. The family feared the boys would be drafted to fight in the Vietnam War. Corky later applied for reclassification as a conscientious objector to the war.

In 1969, Corky was accepted as a VISTA volunteer for a two-year period to serve poor communities of the Lower East Side of Manhattan through the Two Bridges Neighborhood Council, a social service agency with an office in Chinatown.

While working as a housing advocate, he saw the social and political injustices that the Chinese immigrant community faced and quickly realized he wanted to document them. He couldn't afford a camera at first, so he borrowed one.

"Prior to Corky's choice of photography as his tool for social change, there was minimal coverage of Asian communities in the US," John Lee said. "They were the product of white Americans looking at their neighbors of Asian descent as curiosities, exotic at best, dangerous at worst and all too often acted upon their ignorance to tragic consequences."

John believes that mainstream America looked at his community from the outside. Corky was uniquely positioned to show that "we were not the 'eternal foreigner' but Americans in every sense of such title".

From the 1970s on, Corky covered the protests, celebrations, activism and struggles of Asian Americans.

"Every time I take my camera out of my bag, it is like drawing a sword to combat indifference, injustice and discrimination and trying to get rid of stereotypes," the photojournalist once said.

His work didn't just focus on the Chinese community, but also on the Korean, Southeast Asian, Japanese and Filipino communities.

One of his proudest projects was a reenactment through photos of the 1869 completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. The reenactment took place on the 145th anniversary of the railroad's completion, with 250 Asian Americans participating, including direct descendants of the railroad workers, at Promontory Point, Golden Spike National Historical Park, Utah.

Corky was motivated by the fact that Chinese laborers were excluded from the celebratory photos when the railroad was completed. So, he gathered their descendants for the photos as a thank you.

While Corky was in college and John was still finishing high school, they shared an apartment together.

For John, one of his fondest memories of that time was the evenings when they would arrive home from their respective part-time jobs and go down to the public parking lot near their apartment and throw a Frisbee."Eventually our respective modes of activism took us down divergent paths and those sessions ended," John said. "We would still from time to time fondly reminisce about those simpler times."

Corky worked tirelessly for the betterment of his community. He created a Chinese-language ballot that increased voting in New York City. It later led to more Asian American candidates being elected in local, state and federal offices.

He lobbied for congressional gold medals for more than 25,000 Chinese American World War II military veterans. Corky's father was posthumously awarded one in 2021, and the award was accepted by his surviving son.

Toward the end of his life, Corky was documenting how the Guardian Angels — a crime-fighting group — was trying to stop the tide of anti-Asian hate crimes that had flared up in New York City and nationwide during the pandemic. But he contracted COVID-19 and later died.

Looking over his brother's storied body of work, John said that "Corky created a history that truly, accurately and compassionately depicted us as we were, as active a component of America as any other immigrant group that came to these shores".

"He staked the claim for Americans of Asian descent their rights to full participation and recognition in their adopted land, in growing numbers the land of their birth."