|

|

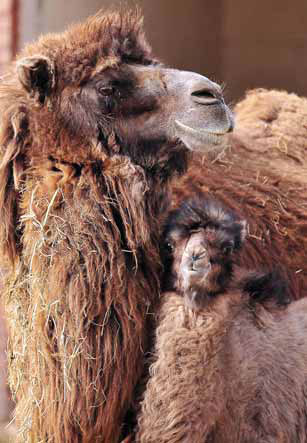

A Bactrian camel calf rests against its mother at a research center in Gansu province, which has achieved success in artificially breeding the endangered animal. Liang Qiang / Xinhua |

Scientists have attached GPS trackers to five wild Bactrian camels living in the deserts of northwest China's Gansu province and the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region to track and better protect the endangered animal - which is rarer than the giant panda. Bactrian camels are the last remaining wild camels. Experts estimate that fewer than 1,000 wild

Bactrian camels currently live in the harsh deserts of China and Mongolia. The animal is listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Liu Shaochuang, a researcher with the Institute of Remote Sensing Applications (IRSA), under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, says the animal's population, migration routes and habits are not clearly known.

"One way to find out where wild camels go, where they drink and what kinds of threats they face is to utilize global positioning satellite technology, which will help experts draw up plans to better protect the wild camels' water sources and define their protection zone," Liu says.

The scientist, who works with two wild camel national nature reserves in Gansu and Xinjiang, entered the Kumtag Desert that borders Gansu and Xinjiang in May and found dozens of wild camels. The largest herd had 36 animals.

Scientists attached GPS trackers to five wild camels that belong to different groups.

Experts say the wild Bactrian camel is the only land animal that can survive by drinking salt water, which they drink not because they like it but, rather, to avoid humans, who cannot survive in deserts without freshwater.

How wild Bactrian camels get rid of the salt and maintain the water balance in their bodies is an interesting subject for scientists.

That wild camels can adapt to harsh deserts where temperatures fluctuate wildly is a miracle. Another remarkable trait of wild camels is that they can cry and do so to wash sand from their eyes.

Compared with domestic camels, wild Bactrian camels, which usually live in herds, have slenderer bodies, thinner legs and lower pyramidal humps. Their powerful noses can smell humans several kilometers away, helping them make fast escapes.

Yuan Lei, a senior engineer with the Lop Nor Wild Camel National Nature Reserve in Xinjiang, says wild camels are not given enough attention in China, partly because they look similar to their commonly seen domestic cousins.

In fact, wild Bactrian camels are a distant relative of their domestic, two-humped counterparts. The ancestors of the domestic and wild camels diverged as early as 800,000 years ago, Yuan says.

Scientists have found that the DNA of the wild Bactrian camel is 3 percent different from that of the domestic camel, which means the two groups are genetically unique and are separate species. The DNA difference between humans and chimpanzees is just 1 percent, and the DNA difference between humans and gorillas is 2 percent.

The positioning data sent back in May showed the five wild camels traveled several hundred kilometers around the Kumtag Desert. Some even traversed the entire desert from north to south.

"During the investigation, we found that humans are often very close to wild camels and are their main threat. If no effective protective measures are taken immediately, wild camels might become extinct within 50 years," Liu says.

A large iron mine is currently being constructed near the northern part of Aerhchin Mountain in southeastern Xinjiang. In order to take a shortcut to transport the minerals, a road crossing the core habitat area of the wild camels was illegally built in Lop Nor, cutting off the animals' drinking route, Liu says.

Illegal hunting, human encroachment and wolves are also threatening the wild camels, Liu adds.

Tao Liaohan, deputy director of the Annanba Wild Camel National Nature Reserve in Gansu, says water is the biggest problem in the nature reserve.

The region has suffered from drought in recent years, and much surface water has dried up. Mining - both legal and illegal - requires a large amount of water, further exacerbating the water shortage. Yuan Lei, of the Lop Nor nature reserve, is not optimistic about the future of the about 500 wild camels in the reserve.

"Since the establishment of the national-level nature reserve in Lop Nor in 2003, people's awareness of protecting wild camels has improved. However, human activities, especially mining, cause great damage to wild animals," Yuan says.

He says protecting wild camels in their native desert habitat is still the major thrust of the project undertaken by China to preserve the population, and artificial breeding is regarded as a last resort.