Take this job and...

|

|

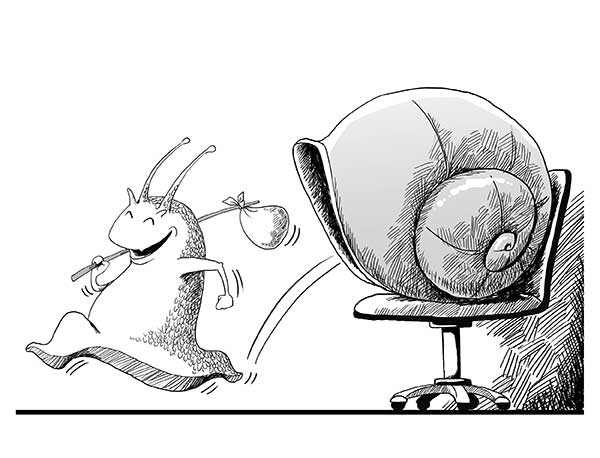

[Photo by Zhang Jianhui/China Daily] |

Young Chinese have very different views on career security, but their impulsive decisions to terminate employment point to growing affluence and the unwillingness to acclimate.

What's a better strategy? To follow your heart and quit a job that's not giving you satisfaction or to stick to it until you find the next, hopefully better, job?

There is a noticeable chasm between China's generations when it comes to such choices. Conventional wisdom has it that those born in the 1970s tend to value job security and would not voluntarily leave their current employers unless they have secured their next position. Those born in the 1990s, on the other hand, would simply get up and do it in a dramatic way, just like in movies-"I can't take it any more!"

This has become so commonplace that some employers are refusing to take "I quit" as an acceptable letter of resignation. They demand something at least 500 words so they'll know why people are leaving.

That is according to a recent post online that presumably recounts a young woman's decision to "fire" her boss and a funny dialogue that ensued between the two parties. As usual, I want to qualify it by saying that this particular story has not been vetted for veracity, but similar stories abound. True or not, it was not an isolated incident, but a general phenomenon worthy of analysis.

We Chinese like to assign numerical names to generations, among others. What is known as millennials in English-speaking countries is divided into "post-1980" and "post-1990" in China.

The terms are nearly impossible to translate because they refer to those born in the 1980s and '90s respectively. Of course, it's simplistic to lump such a big chunk of populace together. For one thing, people have repeatedly pointed out that "post-1985" have more in common with "post-1990" than with their slightly older peers.

That makes the subject of this article the 20-somethings in Western parlance. The use of age group in such discussions has not vanished in the Chinese context; it is just being nudged to the sideline by the years of birth, which can be a permanent label and need not change over the years.

China's 20-somethings are prominent for (a) being single children, (b) being college educated and (c) having grown up with Internet and mobile gadgets. They have just entered the workforce en masse.

And surprising to some, they have displayed a penchant for job hopping. The young woman in the latest story is said to have changed three jobs in a year.

She cited some of the reasons for quitting.

Highest on the list is her employer's policy not to take deliveries of employees' personal orders.

That means she has to go down 21 floors-three times a day on average-to meet the couriers. Her supervisor countered that, if the time she used in online ordering is factored in, that would add up to at least one hour a day for this personal affair alone. Stricter employers would ban such activities wholesale, he said.

Another reason she gave was the pep-talk meetings, during which she had to peep at her cellphone for distraction. She could not bear the lengthy platitudes about corporate values and culture. Her supervisor argued that this form of boredom comes with every job.

I may not have a vantage point for observation, but the young men and women I have known or worked with do not seem to share too much with the above stories.