Tanka communities face wave of uncertainty, Shi Yingying reports in Hainan.

Wen Changgao, 45, fishes in the same way his Tanka grandpa did half a century ago - at night with lights ablaze. "The fish follow our boat's light, giving us a better chance of catching them."

| ||||

Many things changed with that move. And more profound changes are likely, if plans to expand Sanya, on Hainan island, as a luxury resort proceed. New resort hotels, inns and tourist attractions require land, land where many Tanka now live.

"The older generation never wore socks or shoes because there was no need to; they spent their whole lives at sea," Wen said. "My grandfather used to tell me he never actually stepped on land in his entire life. That's why they ('onshore people') call us 'gypsies on the water'."

These "Gypsies" are widely believed to be descendants of participants in a failed uprising in the latter stages of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (AD 317-420). As part of a peace pact with the authorities, these early Tanka people were forbidden to live on land or marry people from the land, or to become public servants.

Over the dynasties, these restrictions became customs, forming the core of the Tanka identity: People were not only born on the fishing smacks, but also grew up, worked and died there. The boys could only become fishermen and the girls married from one fishing boat to another.

Their traditions and dialects evolved drastically different from those who lived on land, yet the Tanka people still see themselves as Han Chinese. In the 1950s, they went as far as refusing to be acknowledged as an independent ethnic minority group.

They began to move to land in the late 1960s. Today, more than 10,000 Tanka people live in Sanya, about half of them in the Yugang and Nanhai communities, which consist of a couple of small lanes packed with a hodgepodge of houses fishermen built next to their workplace, Sanya Bay.

|

Apartment buildings and hotels rise in Nanbianhai in Sanya, a former community acquired by the local government from the Tankas. [Photo/for China Daily] |

Different dreams now

Nobody lives on boats anymore. And fewer Tanka youngsters want to work on them. When they see luxury yachts where their forebears docked fishing boats, they dream of doing business, real estate, aquaculture, opening a grocery - anything but fishing.

"The last thing I would like my son to do is to become a fisherman," said He Jinyi, who is 51 and quit fishing 20 years ago. "I worked on the junk for seven years until I turned 30 and got pregnant. I asked myself: Do I want this kind of fishing life for the rest of my life, for my kid? No!

"I never liked the sea," He said, or the seasickness that came with it. "Plus it's dangerous and tiring." He remembers the day she told the family she was done with fishing. "My husband was convinced, but my father-in-law was shocked and my mother-in-law even cried and begged us to stay."

But He held firm and turned to aquaculture, and was relieved to earn enough to send her son and daughter to college. "I had a salary of about 7,000 to 8,000 yuan ($1,064-$1,216) a year when I stayed on the sea and it increased to 10,000 yuan after I decided to do aquaculture."

She said she encouraged her children to do anything but fish. "Over 90 percent of Tanka's 60-year-olds and above haven't finished their primary school. That's why we were poor and that's why we were fishermen," He said. "With college academic certificates, they can find better jobs."

Belonging to that 90 percent, Wen Changgao looked puzzled when asked whether he ever considered a job other than fishing.

"Of course I did, but what else can I do?" Wen said. "I was forced to quit school because my father wanted me to help him at the age of 15, and it's my 30th year on the sea. I know nothing but fishing."

Zheng Yin, 29, said it was interesting to learn how much his Tanka grandfather's generation wanted his father to become a fisherman, and how his father wished him to do something else.

"I just got married but neither my wife nor I are fishermen," said Zheng, who works on the administrative staff of the Yugang Community Committee in Sanya, where most residents are Tankas. "My dad also sold his fishing boat about 10 years ago, and now he's doing aquaculture."

|

As it becomes harder to make a living by fishing, many Tanka people switch to other businesses or point their children that way. Aquaculture is popular. This man still works on the water, but as a ferryman now. [Photo/for China Daily] |

The culture is fading

As more Tanka kids put on shoes, cover their fishy smell and choose other occupations, many local customs, costumes and living habits fade away.

For example, saltwater song is traditional music sung on occasions ranging from fishing expeditions to wedding ceremonies to gatherings of friends. Tanka people usually write their own lyrics to fit the rhythm and melody of the folk song.

"We're known for being too shy to express our feelings, but we can sing - we have the words at our mouths and melodies in our minds," Lu Gaofa, 68, said.

Lu said he joined the Nanhai Community's saltwater song club, which organizes activities every Monday, Wednesday and Friday nights to keep the tradition and promote it to the younger generation. "But it's a pity to see only those above 50 years old are fond of our own songs. Not a single young man or woman would like to join us."

The Tanka dialect is fading, too, as three students learned last year while researching a project for a course on Cultural Dimensions of Language and Communication in the University of Hong Kong's School of English.

"The Tankas used to live close to each other in the past and the community was also very small and condensed. Hence, the language and culture would be more likely to be maintained," students Ho Wing-lun, Lam Ka-yee and Ng Tik-lun wrote on their blog, Tanka Community. "However, for today, the younger generation gradually moved away from these houses (the fishing boats) and went onshore, lived in a more urbanized area for better job opportunities. The language is less likely to be kept."

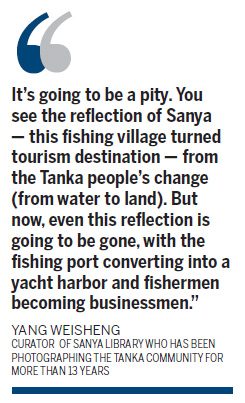

The survival of the people took priority, according to Yang Weisheng, who has been photographing the Tanka community for more than 13 years and is curator of Sanya Library. "The overwhelming liabilities of lost lives caused by drowning during the monsoon seasons explained why they moved."

Yang said many fishing boats took shelter in Sanya harbors from typhoons, and many of them stayed, saturating the harbors. "On top of it, the shabby boat-houses weren't that pretty to look at in the eyes of local government.

"The government enclosed the land of Yugang Community and Nanhai Community" for the Tanka people in the 1970s and '80s but didn't provide housing there, Yang said. "Most fishermen earned enough money to build homes themselves," he said. Fishing paid better in those days.

And now? "I heard they (local government) are thinking about kicking us out of Sanya Bay and changing our residence to the nearby town," said a fisherman who is about 30 and gave only his surname, Chen. He was spending the day making fishing nets in Nanhai before going out to sea at night. "Sanya Bay is the best bay for us and I can't imagine the days living far away from here."

|

Tanka women are skilled at knitting fishing nets. [Photo/for China Daily] |

Luxury moves in

Few people know what exactly lies ahead. The Sanya government has made no announcements. And, despite a visit to Hexi District Committee and 12 phone calls to the Sanya government's publicity department over four weeks, the government has not directly responded to questions about any land development plans that would affect the Tanka residents and where the Tanka would then live.

However, luxury hotels and expensive private houses have found homes along the city's lush, coconut-lined beaches, and the city's 10-year plan says more are on the way. Chen Minjian, deputy director of the Sanya Tourism Industry Development Bureau, told China Daily that 27 top-grade hotels are expected to be built in Sanya within 10 years, more than doubling the current inventory.

Some of that depends on the economy, of course. Sanya's vice-mayor, Li Baiqing, expressed his personal concerns about a potential real estate bubble.

"Sanya seems to represent a bigger problem that is emerging on the mainland. Personally I'm very worried about the property speculation that is going on, but it seems like the rest of the city isn't," Li told China Daily.

Wang Huya, director of the Department of Fisheries for the Hexi District, which includes Sanya's Yugang and Nanhai communities, had this to say:

"Tanka people and the local government haven't reached agreement on the migrating; that's why the plan has been laid aside at the current stage. The major disputes focus on complaints of low compensation and the new residency location too far from Sanya Bay."