Villagers battle to maintain their proud tradition of learning, Gao Qihui reports from Fujian.

The Peitian village primary school in western Fujian province opened for its spring semester with 29 children enrolled in classes from first to fourth grade. In the 1970s, 375 pupils attended classes up to sixth grade.

Two villagers visit a calligraphy exhibition, works by their neighbors, in a classroom at Peitian's primary school. Xiang Huazong / for China Daily |

The shrinking numbers are typical of many areas in rural China, but it has added poignancy for Peitian residents. Their village has a storied history of scholarship dating back more than 500 years.

But times change, and with it priorities that reach well beyond villages:

In 1982, the State introduced a family planning policy to the Constitution that curtailed family size. The number of primary school-age children declined 20.3 percent from 1980 to 1990.

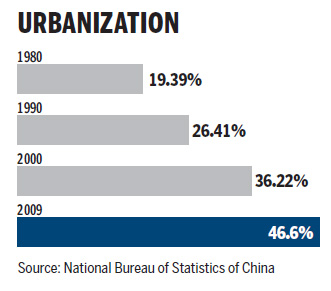

Urbanization increased, from 19.4 percent in 1980 to 36.2 percent in 2000. Rural residents moved to towns and cities seeking work, often taking their children with them.

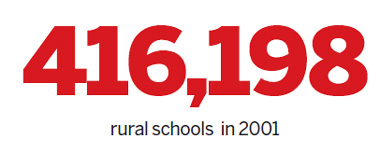

Enrollment in rural schools dwindled, and the State determined it could find a better way to distribute resources for education. It began a wave of centralizing primary schools in the countryside in 2001.

Which brings us back to Peitian, where the school's very existence is under threat. The villagers are fighting to maintain their tradition of educational achievement and have gained - and broken - some ground.

The two-story school, built in 1994, sits across a playground from a tree-shaded academy that was built at least 300 years ago. The old building provides temporary offices for the village committee now, and it symbolizes the scholarship the village has fostered.

During the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, 238 villagers passed the county-level or higher imperial examination. Since the People's Republic of China was founded in 1949, more than 270 students have entered universities and professional schools.

Peitian Hakka Community College was established in 2010 with the support of six NGOs. Xiang Huazong / for China Daily |

A tradition of stressing education has been passed from generation to generation in Peitian, which was settled centuries ago by Hakka people from Zhejiang province. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, wealthy residents supported local education by providing scholarships for poor people and by employing scholars as teachers.

Even women were encouraged to study during the Qing Dynasty, despite the prevailing wisdom that ignorance in women was a virtue. Millionaire villager Wu Changtong built Rongxi Ju, an academy for women, during the reign of Emperor Xianfeng (1850-1861).

In modern times, too, Peitian's renown attracted outsiders. "When I was a student, the Peitian school had a good reputation for education and many non-native students came to our school to study," said Wu Zhixi, a 70-year-old villager.

There are fewer native students now. More than 60 babies were born in the village in 1972, said Wu Laixing, who was director of the village committee 1972-1982. Now about 10 babies are born each year.

Even those born there may not stay for long. Nearly 500 of Peitian's 1,467 residents have gone away to work elsewhere, said Wu Qingxi, the current village committee director. And migrant parents are more willing to take their children with them, said Cao Changyuan, principal of the primary school.

Going away to school

As rural schools were centralized for better economy and to improve quality, parts of all grades were merged into township central schools, where resources were focused.

The number of rural schools nationwide fell 43.7 percent from 2001 to 2009, and the number of classes in rural areas dropped 35.7 percent, according to statistics from the Ministry of Education.

Peitian's primary school has survived, though not without losses. Grades 3-6 were moved to the central school in Xuanhe township in 2008 because teachers for them were no longer provided. But grade 3 was restored in 2009 and grade 4 in August 2010.

Still, 29 students are not enough.

Not everyone thinks the central schools are a better option, especially for children as young as 8 or 9. Students can board there, but the schools can't provide a totally safe and comfortable living environment, said Wu Meixi, a former principal of Peitian primary school.

There's extra expense for boarding services, or for the daily commute to the school in Xuanhe. Some children ride their bicycles nearly 3 kilometers each way, and parents worry how safe they are sharing a concrete road with cars and trucks.

And a recent study by the China Development Research Foundation found nutritional deficiencies among children, many of whom lived in boarding schools, that resulted in stunted growth and could harm their intellectual growth.

There's a potential emotional toll, too, said Qiu Jiansheng, an expert on rural development at Beijing-based Renmin University. Qiu said that ties to home and family can weaken when children are home only on weekends.

And there's a threat to this village's centuries-old culture, tied so strongly to education, Qiu said. The village committee and advocates from outside are working to salvage that culture.

Internal, external help

After the school was reduced in 2008 from six grades to two, the committee sought support from the government on the teacher supply by negotiation. Members went door to door, trying to persuade parents to let their children stay in the village school, to justify their appeal for restoring grades. Grade 3 was restored the next year.

The village couldn't afford to hire its own teachers to replace those the State no longer provided, but it does sponsor a kindergarten class. With annual revenue of less than 50,000 yuan ($7,600), the village spends at least 7,000 yuan a year for the teacher's salary and about 13,000 yuan more on education overall, village committee director Wu Qingxi said. That makes it hard to squeeze out more to employ enough teachers.

The committee also has found angels in enthusiastic scholars from elsewhere. One is Wang Li, a researcher at Beijing-based 21st Century Education Research Institute who became involved after visiting Peitian as a tourist in January 2010.

Wang was impressed by Peitian's history of education. "I cannot bear its death and I want to save it."

She chose the primary school as the basis of her efforts and drew support from the village committee. In about seven months, she won over the government, which agreed to restore grade 4 to the village school in August 2010.

Villagers are encouraged by this rebound. "We intend to add the fifth grade this year and restore a complete six-grade primary school next year," Wu Qingxi said.

Additional support arrived in July 2010 when six non-governmental organizations and the local government jointly established Peitian Hakka Community College. The college has employed an English teacher for the primary school.

Adding classes is the only way the school can attract students, Wu said. "As long as we try hard, our Hakka education can be revived. This is our aim and a cultural inheritance."

However, reality is undermining the base of Wu's blueprint.

Wu Zhixi, a senior villager with abundant enthusiasm for Peitian's tradition, persuaded his son to call his fourth-grade grandson back to Peitian after grade 4 was restored. "My grandson is too young (for boarding school) and it is more reassuring if we bring the child back so that we can take care of him at home."

But the grandfather now regrets his decision. He learned that the man hired to teach Chinese to his grandson is 62 and was a school entrance guard for 12 years.

"If the teacher is not eligible to teach, it will harm the children's studies," Wu said. He has decided the little boy should attend township central school again next semester.

Nontraditional approach

The fundamental education for pupils in Peitian may face an uncertain future, but the village is pinning its hope of saving the educational tradition on the community college

The first of its kind in Fujian province, the college commits itself to educating masses of people without limitation and to village development, said Shen Jiasong, the school's only permanent executive staff member.

It offers free training classes to villagers to enhance their educational level. Most are taught by volunteers.

"We provide computer training to adult villagers and teach students calligraphy and English," Shen told China Daily. More than 100 villagers have been trained in the computer classes.

As part of the village development program, the college also helps villagers form craftwork cooperatives to teach them Chinese paper-cut and weaving arts.

Programs aren't limited to the teaching of skills. The college has started classes on Hakka history and cultural tradition, which Qiu Jiansheng believes are necessary. Qiu is the expert at Renmin University who also is key administrator of this community college.

The classes can help people understand and inherit their traditional culture, he said. They'll also promote a sense of self-identification in the village, which may finally lead young people back home.

Qiu thinks the outflow of youth from the village is eroding the traditional culture. "We cannot marginalize the villages during urbanization and modernization," he said.

Sponsors plan to develop the community college as an international base for Hakka culture.

"I think the community college is the best platform to revive Peitian's tradition of education," said Wu Laixing, who also helped establish the community college.

"Now more and more people have started to pay attention to the countryside education and I believe the prospect is bright," Qiu said.