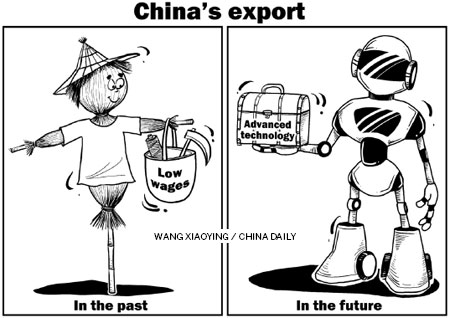

For years, the abiding view of China has been of a workshop powered by waves of young migrants able to out-compete workers elsewhere in the world because of their low wages. This image is becoming increasingly wide of the mark.

The wage of an average migrant worker in China has quadrupled in US dollar terms since China joined the World Trade Organization at the end of 2001. The average Chinese factory worker now earns more than twice as much as his or her counterpart in Indonesia or Vietnam.

Average wages are increasing at a double-digit pace even today, though the Chinese economy is on course to record the lowest annual GDP growth rate this century. If rapid wage growth continues - and former Communist Party of China general secretary Hu Jintao's recent pledge that people's income will double this decade suggests the Chinese government thinks it will - wages in China will soon surpass those in Mexico and start getting close to wages in Brazil.

Many people are worried about the strains the wage increases are putting on exporters, who are already struggling owing to sluggish global demand. There are signs that China's dominance in certain sectors is starting to slip. For example, its share of the world's textile market started declining recently.

But a closer look at the shifting patterns of trade suggests this is the result of a welcome move by enterprises into sectors where margins are higher rather than a failure to compete. In fact, China's share of overall global exports has continued to edge up, with Chinese companies becoming increasingly important players in more technically advanced industries.

There are three secrets to China's export success. First, by engaging in regional production chains, Chinese enterprises have been able step by step to absorb advanced technology and upgrade their skills. According to the World Bank, more than a quarter of China's manufactured exports are hi-tech, one of the highest proportions in the world. As a result, workers these days are far more productive than they were a few years ago, with their increased output helping make up for the higher wages they are paid.

Second, the sheer size of China's manufacturing workforce plus a focus on investment in factories and the infrastructure that surrounds them allows Chinese enterprises to respond quickly to shifts in demand and ship their goods to market faster and at lower cost than their overseas rivals.

Third, many enterprises benefit from generous government support in the form of cheap loans and a supportive currency policy. Opinion is now divided on whether the renminbi is close to "fair value". But exporters in China have the luxury of knowing that the People's Bank of China will intervene if needed to prevent a sharp appreciation in the Chinese currency.

The clearest evidence of the competitiveness of China's exporters is their continued ability to undercut companies' elsewhere in the world. The prices of the goods that China exports to the United States, still its most important market, have barely increased since the start of 2009 (they are up just about 2 percent). This is all the more remarkable because the renminbi has appreciated substantially against the dollar over the same period.

Most significantly, the prices of manufactured goods imported by the US from elsewhere in the emerging world have risen four times as fast. This ability to raise productivity enough to keep prices low explains why China's exporters have continued to expand their share of the global market, even though they no longer have the advantage of cheap labor.

Of course, today's success provides no guarantee for the future. If exporters are to succeed against a backdrop of continued rapid wage increases, they will have to continue grinding out improvements in productivity.

There may also be a limit to how high China's share of global exports can rise before it triggers a protectionist push back from trading partners. For most of the period since the launch of economic reforms, China's emergence as a global export powerhouse followed a similar path to that traced by Japan 30 years before. But whereas Japan's share of global exports peaked at one-tenth in the 1980s, China's share passed that level two years ago and has continued to rise. If this continues, the pledge of Mitt Romney, who contested the recent US presidential election against President Barack Obama, to designate China a "currency manipulator" is unlikely to be the last such threat that China faces.

But the major implication of China's transition from being the world's low-end producer is that it will create new challenges and new opportunities elsewhere. This shift is bringing Chinese enterprises into competition with more established companies in the middle-income economies of Asia and Latin America and forcing them to innovate to stay ahead.

As China leaves unskilled, low-end manufacturing behind, others have a chance to occupy that space. Vietnam, the Philippines and Indonesia are particularly well placed to benefit.

The author is chief Asia economist at Capital Economics, a London-based independent macroeconomic research consultancy.

Top 10 overseas M&As of Chinese auto companies

Top 10 overseas M&As of Chinese auto companies

Chinese factories score a goal with Euro 2016

Chinese factories score a goal with Euro 2016

Young car racer pursues dream, speed

Young car racer pursues dream, speed

Flying forward, once again

Flying forward, once again

Outbound travelers shrug off declines in yuan value

Outbound travelers shrug off declines in yuan value

China's top 10 counties most active in e-commerce startup

China's top 10 counties most active in e-commerce startup

Iconic pagodas turn into a dreamland in infrared photos

Iconic pagodas turn into a dreamland in infrared photos

Top 10 most valuable car brands in the world

Top 10 most valuable car brands in the world