Top Biz News

Pressure builds on employees

By Wang Zhuoqiong (China Daily)

Updated: 2009-11-24 08:00

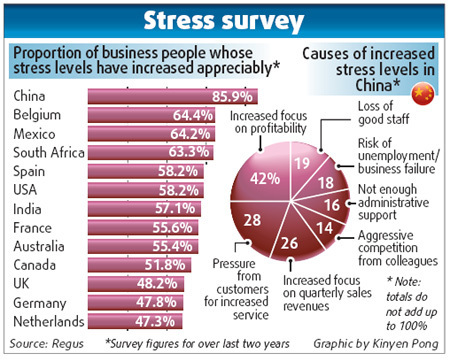

Nearly nine out of 10 Chinese workers are under growing pressure at work as China leads the world toward economic recovery, a global survey has found.

The survey by Regus, a US-based provider of workplace solutions, polled 11,000 companies in 13 countries during August and September. It found 58 percent of companies worldwide had seen a rise in workplace stress during the preceding two years.

"Nearly 86 percent of Chinese people report that their levels of stress had become 'higher' or 'much higher' during the past two years," the survey noted.

The smallest increase in stress worldwide was felt in Germany and the Netherlands, with a respective 48 percent and 47 percent of workers saying they had experienced more stress.

With the World Bank forecasting China's GDP will grow by 8.4 percent this year, indicating the country is well on the way to recovery, Chinese workers are at the sharp end of the world's efforts to rebound.

"While their international counterparts feel stressed as a result of the global economic downturn, the stress faced by Chinese workers is twofold," said Hans Leijten, regional vice-president of East Asia for the Regus Group. "On the one hand, they must react fast to the new opportunities provided by a country that maintains a higher-than-8-percent GDP growth. On the other hand, they have to deal with the retraction challenges presented by the global economic downturn."

Among the stressed workers, 28 percent said maintaining excellent levels of customer service was the main reason for their sleepless nights.

Another survey, from the Horizon Research Group, said respondents quizzed in June complained that the global financial crisis had contributed to rising pressure among Chinese workers.

About 34.2 percent of people interviewed for that survey said the crisis had increased workplace pressure.

Those most affected by the added stress were in the 24-30 age group and the majority worked for foreign-invested enterprises, the report said.

Most of the pressure at work came from career development, performance appraisal and salary issues.

In the midst of the downturn, employees were involved in fewer malpractices, were more likely to volunteer to do overtime and more inclined to postpone planned leave.

Both surveys reflect Chinese society, where many employees are inclined to put in long hours.

"Karoshi", or death from chronic overworking, is no longer a phenomenon reserved for the Japanese. In China, there have been reports of employees dying on the job. Early this month, a young software engineer at a video website died at his desk after putting in a series of 13-hour days.

"The pressure does not necessarily ease with different economic situations," said Sam Liu, a 31-year-old marketing strategy manager with a global company. "You have one kind of pressure in good times and another kind in bad times.

"I have time to sleep. But I have to sacrifice my hobbies and the time I would like to spend with my friends."

Among the reasons why some Chinese people work so hard is the massive competition within the vast workforce.

"There is always another guy who is willing to do 12 things when your boss has asked you to do 10 things.

"You deal with the pressure or you quit," Liu said. "It is up to you."