Consumer rights need further work

By Li Yang (China Daily) Updated: 2014-03-15 08:04

Other media outlets have reported that many companies increase their ad spending on CCTV ahead of the annual program "to avoid trouble," as some put it.

That allegation has been supported by some production staff involved in 3.15 Evening. Moreover, as the Internet expanded in China, a host of websites emerged offering to help companies delete negative posts about their operations or products.

Some of those posts are actual consumer complaints. Others are fabricated criticisms planted by competitors. The media actually can play a positive role in addressing consumer issues in some new areas, such as e-commerce and online finance services, which aren't fully covered by current laws.

Consumer culture

China's former planned economy, based on a strict rationing system, meant that Chinese people had no idea of consumerism, much less consumer rights.

There was nothing much to buy-indeed, buying and selling were mostly illegal. It was only when reform and opening-up began in the late 1970s that the concept of consumption emerged.

Material shortages in the 1980s exacerbated Chinese citizens' longing for "stuff", under any conditions.

Many people now in their 60s and 70s recall the 1980s as an era where "no rights existed in our awareness, except that of possessing," as one retiree put it.

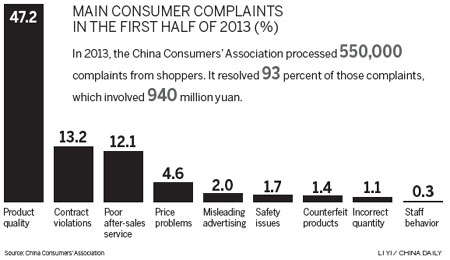

A Chinese consumers' association was established in 1983, and the global consumer rights day began to be observed in 1985.

Yet, Chinese didn't form a deep sense of consumer rights until the early 1990s, when there was a wave of faulty and defective products, some of which caused injuries and deaths, and deceptive and misleading ads.

That was the era in which CCTV's annual muckraking program was born.

The first consumer rights law only came into being in 1994, and even then, it still wasn't easy for citizens to seek redress against companies providing shoddy or dangerous goods.

The plight of consumers provided great fodder for the media to frame itself as a defender of the public interest.

China revised the law in late 2013, making it easier for consumers to defend their rights and more expensive for businesses to break the law.

But even now, Chinese consumers don't see the law as their first choice in disputes with companies.

According to a survey by Beijing Youth Daily, only 5.2 percent of respondents said they would sue companies directly. The rest said they'd negotiate with dealers and producers, because the legal process is too lengthy and expensive.

|

|

- NHTSA says finds no 'defect trend' in Tesla Model S sedans

- WTO rare earth ruling is unfair

- Amway says 2014 China sales may grow 8%

- President Xi in Europe: Forging deals, boosting business

- CNOOC releases 2013 sustainability report

- Local production by Chery Jaguar Land Rover this year

- Car lovers test their need for speed in BMW Mission 3

- China stocks close mixed Monday