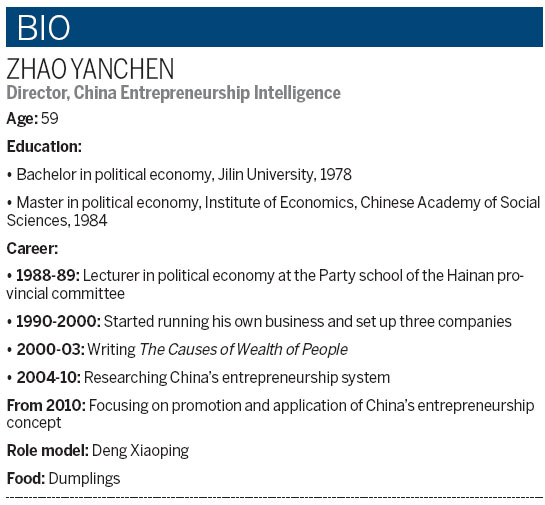

Zhao Yanchen, 59, a native of Jilin province, is widely recognized as the founder of the entrepreneurship discipline system in China. He chairs China Entrepreneurship Intelligence, a national organization that promotes entrepreneurship.

He was once an economic scholar, publishing many influential articles and became a provincial departmental-level official of Hainan province. But in 1989 he gave up his position and went into business.

"When I was a scholar, I wrote and lectured about economics theories to entrepreneurs and students, mainly based on collected materials and cases from China and overseas," he says. "But I knew that one's horizon and depth of knowledge is limited by one's experience.

"When I realized that all my theories and writings were of little interest to anyone, I decided to go into business and experience the market economy after reform and opening-up began in the 1980s."

He set up four companies over the next 10 years through thick and thin, managing not only to survive but to turn a profit. He did that through methods such as adjusting the scale of operations, reducing costs and innovating. With one company he was able to make about 3 million yuan ($495,000) in the first two years.

In 2000 he made another big career change, abandoning business and taking up writing.

"I think there are some inner rules about how to make a company and a project grow out of nothing, then survive," he says. "I wanted to write down my thoughts so people could learn from my failures and success."

It took him three years and 14 days to finish writing The Causes of Wealth of People in the remote Yuanyang Valley of the Huangshan Mountain in Anhui province. The only book he took with him was Tao Te Ching (or Daodejing) by Lao Tze, the founder of Daoism, which he thought would have great impact on Chinese culture and people's behavior.

After the book was published in 2004 he received more than 10,000 letters from readers, he says. He has since written 18 more books to illustrate ideas he expressed in the book and explain how to put his ideas into practice.

He came up with the idea of translating the book in 2006 when an entrepreneurship wave swept across China. That year at Tsinghua University he attended a dialogue with US scholars about entrepreneurship.

"There was an enthusiastic audience in the hall, and they treated him like a rock star," says Zhao Jing, who met the author for the first time at that event.

Zhao Yanchen commissioned a well-known Chinese translator to translate the book, but the translator found it too difficult. He then asked Zhao Jing, who grew up in China, but has lived in the US for more than 15 years and had started a business. For the past 10 years she has been teaching Westerners and Chinese how to deal with each other and their respective countries.

Zhao Jing says that she used to think she clearly understood both Chinese and Western cultures and that translating the book would be easy, but she was in for a surprise.

"It's relatively easy for someone who understands both cultures to read the book. But for pure Westerners it is very difficult because the book is particular to China and its culture, so how to translate it properly left me perplexed," she said.

She got literary experts to look at her translation, but found many cross-culture problems, which they thought too difficult to solve. So she turned to her husband Joseph Cesarone, who had helped in revising her translation projects before.

"When she took this book on, it sounded intriguing, given both my long-standing interests in economics and in China, as well as my new and growing interest in entrepreneurship," he says. "Upon first reading the book I knew that it would not be an easy project, but I knew it would be a very interesting, worthwhile and rewarding endeavor."

Cesarone says they have worked on it periodically over two years, and he contributed about four months on it full-time.

One thing that made the translation difficult is that it is written in a rather poetic and free-form style, which they wanted to preserve as much as possible without losing the meaning or confusing the reader. That was a delicate balance to achieve, he says.

There are also many Chinese cultural references that were used to make a point or to add humor, which by themselves would be lost in translation to most Western readers. They had to add explanatory text here and there without it becoming a distraction.

Finally, there are various novel concepts in the book, such as "soul capital" and "root capital". They were keen to ensure these terms were translated as accurately and consistently as possible, Cesarone says. "To me, the most interesting parts were Mr Zhao's personal anecdotes of his own entrepreneurial efforts and those of other entrepreneurs whom he assisted, as well as the Eastern philosophical underpinnings to his theories, such as the Tao of entrepreneurship and the relevance of Sun Tzu's Art of War to entrepreneurial efforts."