|

CHINA> Regional

|

|

2010: a performance-space odyssey

By Wang Zhenghua (China Daily)

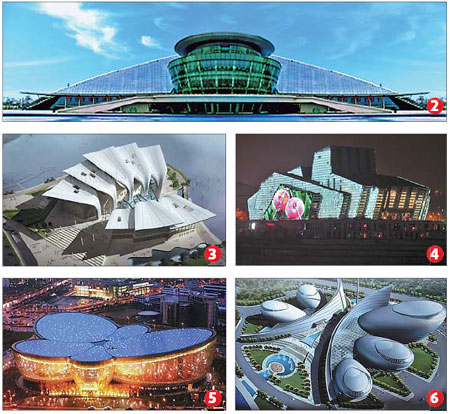

Updated: 2009-07-24 10:15 One of just four expo buildings to become a permanent fixture of Shanghai's landscape after the six-month event comes to a close next year, the futuristic Expo Performance Center will serve as a grand structure set to symbolize the city's forward-thinking as it pushes ahead in the world of art culture.

Dubbed the Flying Saucer because of its sci-fi look, one of the 2010 Expo's most significant buildings will mark the first indoor venue of its kind in China, featuring modern technologies like convertible seats and accommodating crowds of up to 18,000. With a staggering cost of 1.1 billion yuan, the Expo Performance Center will host high-profile shows and performances during the 184-day mega-event.

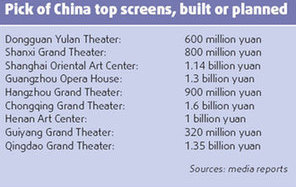

Ushering in a steady following from those eager to match the recent prosperity and achievements of Shanghai, local governments have taken it upon themselves to create their own versions of the Expo Performance Center. But these moves have stirred a buzz of questions surrounding the kind of nationwide influence the Expo Performance Center is having on its Chinese neighbors ahead of its completion at the end of this year. While cities like Ningbo and Guangzhou race to build their own theater empires, which come at a high cost of billions of yuan plus tens of millions of yuan more in annual maintenance, critics are shaking their heads. According to Yu Jian, the former head of the Zhejiang Research Institute of Stage Design, such decisions are made recklessly, without giving thought to long-term urban planning realities. He described competition among local governments in showing their strength as the cause of such ill-informed agendas. "Many of these projects are started because of the government leaders' intentions to show they are capable of such achievements," he said. "But these theaters are created in such frenzy and only end up being a huge waste of money." In Zhejiang province, Ningbo has proposed to build an 18,000-seat multi-functional performance center in partnership with AEG, a world provider of sports and entertainment. Both parties inked a 1 billion yuan deal at the end of last year, which was to see construction start on the 362,000-sq-m project this year in the city's east end, but those plans are now in limbo. One government official said the project is still "under negotiation" while local media reports said the initial demolition of houses to make way for the center had already begun. "It will be disastrous," said Yu. "I don't see how there can be a need for such a grand facility to house high-profile cultural events in a coastal city of 5.7 million people." Besides the coastal city already has a grand theater that opened in 2004 at a cost of 619 million yuan. In similar moves, Guangzhou has promised 1.6 billion yuan to build an 18,000-seat complex. The Guangzhou International Sports and Entertainment Center, is on track to being completed next September. Covering an area of 65,000 sq m, it is set to become the nation's third-largest comprehensive sports and entertainment facility following the Beijing Wukesong Gymnasium project and Shanghai's Expo Performance Center. Likewise, the coastal city of Wuxi in Jiangsu province is rumoured to spend hundreds of millions of yuan to build a similar project near Taihu Lake, giving rise to environmental concerns. Critics charge that more cities will only continue to step in line to build these luxurious performance centers, which cannot be adequately sustained. They point to Beijing's National Center for the Performing Arts as a case example. Adjacent to the city's landmark structures like the Great Hall of the People and Tian'anmen Square on Chang'an Avenue, the 3-billion-yuan building completed in 2007 was designed to mark a new era for the capital, but two years later it has been running on the support of government subsidies. Despite its failure an estimated 1,000-plus theaters imitating its design have since sprouted up across the country. Supporters such as Shen Di, vice president of Shanghai Xiandai Architectural Design Group, have described the rush as answering the call of residents' increasing demands for artistic culture. Yet critics argue the aesthetic value is often trumped over functional use. Architects are often hired to design the building's exterior prior to planning performance stage logistics. "They build it like a sculpture, not a theater," said Yan Xianliang, a researcher at the China Art Science Technology Research Institute, adding such costs outweigh the actual advantages. Yan described one such case in which a southwestern Chinese city which squandered 1 billion yuan to build such a center. The city generated 22 billion yuan in government revenue last year. Focused on acquiring international connections, these projects also fail to give Chinese companies the chance to grow their skills in architectural design, as they are usually only given to foreign companies. Yan pointed to another case that saw the city's party chief scrap plans after it was discovered the original bidding came from a domestic firm. Yet, it is ironic the international features of so many of these structures cannot manage to generate enough profits. Many remain empty for much of the year, forcing governments to spend tens of millions of yuan more on building maintenance. "About 300 performances a year is the norm for a modern theater, but less than a third of them meet this goal," said Yan, adding that the government needs to enforce stricter standards on the erection of such buildings. As Shanghai looks to its Expo Performance Center to impress 70 million expo visitors, many of its Chinese counterparts look at the expo city, confused about how to achieve such pride and glory, added Yan. |