Hot on the Web

On the road to Tragedy

By Xin Dingding (China Daily)

Updated: 2009-10-28 09:14

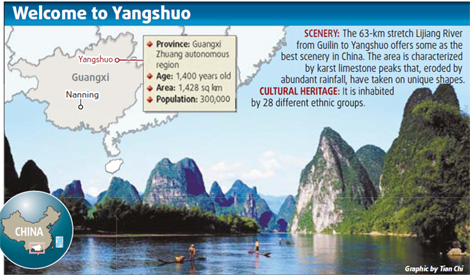

The blue skies above Yangshuo are usually dotted with hot-air balloons, each loaded with Chinese and foreign tourists eager to get a bird's eye view of the county's famous karst peaks.

Today, there are none. Local authorities grounded all flights after the tragic death of four travelers on Oct 14.

The victims were among five Dutch passengers on a hot-air balloon that burst into flames as it landed on a small hill just outside Yangshuo county, which sits astride the Lijiang River in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region.

"The basket fell over, which is not unusual, but somehow the burner (which heats the air in the balloon) didn't go out and something caught fire," Ronald van der Weerd, a local hotel owner who had talked to the surviving tourist, told Radio Netherlands Worldwide.

"The pilot caught fire and fell out of the balloon, along with his assistant and one of the passengers."

What happened then remains unclear, but eyewitnesses said the balloon rose into the air before the basket caught fire and the four passengers jumped to escape. None survived the fall.

"I can't remember any accidents like this since companies started running hot-air balloon rides here five or six years ago," said Huang Hao, a 26-year-old salesman for a local tour agency.

The incident sent a shockwave through the town and some have welcomed the decision to ban the hot-air balloons while local officials investigate the incident.

But the tragedy has led many to ask the question: Exactly how safe it is to travel in China?

Judging by official figures, the answer is very. Of the 1.7 billion domestic and overseas tourists last year, there were just 147 deaths, with four missing and 401 injured, according to the China National Tourism Administration (CNTA).

The statistic is impressive, considering studies by the Japan Travel Bureau have shown one fatality occurs in every 60,000 who travel abroad, said Li Xinjian, associate professor at the Beijing International Studies University.

Traffic collisions are the chief cause of fatalities among tourists in China, with 80 people killed last year in 30 road accidents, usually involving overloaded buses, said CNTA officials. The other major killer was the May 12 Sichuan earthquake, which claimed the lives of 54 travelers.

Some experts warn the death rate could be higher than that recorded by the CNTA, however, as these figures only cover tourists in groups organized by travel agencies.

"Those killed in a car accident or flood while traveling independently are not included in these statistics," said Wang Jianmin, a professor in travel law at the China University of Political Science and Law in Beijing.

But as car ownership continues to grow, so too does the number of independent travelers. And in August, they accounted for 65 percent of all tourists, said Dai Bin, deputy director of the China Tourism Academy.

The media in recent years has carried a handful of stories about deaths during self-organized expeditions, the latest being in July when 19 tourists drowned in floods in Tanzhangxia Valley, Chongqing municipality.

The deceased were part of a 35-strong group that planned the trip via an online forum and, according to locals, ignored flood warnings after days of heavy rain.

Although accidents are happening more to independent tourists, there is no reflection of the trend in the official figures, said Wang.

Loopholes also exist in the supervision of Chinese travel companies, and many experts insist that a tightening of the regulations could save hundreds of lives.

"The Yangshuo incident highlights a typical problem in China: several government departments often share the responsibility of supervising one sector. It usually results in none of them doing the job," said Wang.

Cheng Peng, general manager of a Beijing-based hot-air balloon club, agreed and said to start his business he needed a green light from several authorities.

"An owner needs pilots with licenses issued by the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) and facilities made by qualified producers. They must also register the relevant documents at the local commercial bureau, report to the local aero-sports association and apply to the air force to use the local airspace," he said.

The firm at the center of the Yangshuo tragedy, Myflying Club, was fully registered in Dongguan, Guangdong province, and even had approval from the regional CAAC to carry out general aviation tasks, "which not many balloon clubs get", said Cheng, who has been in business for a decade.

Myflying Club's license, which was issued in July, restricted the firm's hot-air balloons to a height of 200 m and radius of 6 km around Lianfeng village. However, preliminary investigations into the Oct 14 accident showed the pilot broke both of these limits.

"The problem is that, after approval is given by the various government departments, a company which uses its balloons for commercial flights is basically not overseen by any of these departments. Safe or not, it all depends on an enterprise's social responsibilities," said Cheng.

Only balloons used in sporting events are given regular checks, which are conducted by the General Administration of Sports, he said.

Officials from bureaus covering safety supervision, tourism, civil aviation and sport have all been sent to Yangshuo to probe the incident, but it is still unclear which department should be in charge, Xinhua News Agency reported on Oct 19.

Wu Gongyu, director of the balloon committee under the China National Aero-Sports Association, also admitted the supervision mechanism for commercial hot-air balloon flights was "incomplete" during an interview with Beijing News.

Experts and tourist associations have called for renewed efforts to streamline the supervision of travel agencies, particularly firms that run potentially dangerous tours.

It would be hard to argue China does not have laws to protect tourists. Commercial hot-air balloon companies alone must adhere to the Law of Civil Aviation, Basic Regulations of Aviation and Management Measures on Hot-air Balloon Sports.

However, it is the implementation of the rules that is the focus of criticism.

"There is no one government department making sure the law is being strictly followed. Violations only come to light after accidents happen, such as the one in Yangshuo," said Cheng.

An official with the CNTA's department of public service said the country has regulations and management measures to ensure travel firms protect tourists groups from danger. But Dun Jidong, a spokesman for the State-owned China Travel Service, the first to be set up in China after 1949, said some smaller agencies are potentially putting customers at risk by lowering their standards to cut costs amid fierce competition.

The companies breaking the rules, though, are only exposed if an authority receives complaints from unhappy clients. In serious cases, a firm's license can be revoked.

Travel law expert Wang also said the government control on scenic spots has also hindered the implementation of safety orders issued by CNTA. Thousands of China's historical tourist attractions fall under several government departments, he said.

According to official statistics from 2005, more than 2,800 State-level cultural relics, such as the Palace Museum and the Summer Palace in Beijing, come under the Ministry of Culture; almost 200 national-level scenic areas like Mount Emei and Jiuzhai Valley, both in Sichuan, under the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, and some 565 national forest parks under the State Forestry Administration.

The ministries of agriculture, environmental protection, and land and resources also cover a number of scenic spots, while others, such as Mount Huangshan in Anhui province, are listed companies.

"As the CNTA does not have any authority over scenic spots, its orders to ensure the safety of visitors could be ignored," said Wang. "China may be growing in tourism but there are many more things to be done and learned.

"The Yangshuo accident may turn out to be the force that pushes the government to improve its supervision of travel firms."