Society

Tragedy reignites debate on forced demolitions

By Huang Zhiling and Liu Weitao (China Daily)

Updated: 2009-12-08 07:56

On Nov 13, 47-year-old Tang Fuzhen shocked the nation by setting herself ablaze in an act of protest against the demolition of her former husband's garment processing unit in Chengdu, capital of southwestern Sichuan province.

Days later, the severely burned Tang succumbed to her injuries at a city hospital.

The act, while not an isolated instance of such an extreme form of protest against "forced demolitions", nevertheless left the nation in a daze.

Relatives and residents of Jinhua village in Chengdu's Jinniu district, where her ex-husband Hu Changming's 2,000-sq m building was located, have poured scorn on the local government for its inept handling of the issue.

Angry netizens too joined in, criticizing the local authorities for the violent way in which the law was enforced, even as the local government insisted it was only doing its job.

The uproar has yet to die down, and the incident has triggered a debate of sorts on the "forced demolitions" that are rampant across the nation.

Xiao Rong, a middle-aged government employee in Jinniu, is one such concerned citizen who has been following the tragic development ever since it happened.

"It is not just because it happened in my district, but because similar incidents have taken place across the country in recent years," Xiao told China Daily. "Any public-minded citizen has to follow the case."

The tragic tale has its genesis in 1996 when local authorities tried wooing investors to develop its economy. It was then that Hu signed an agreement to rent land, after paying 40,000 yuan ($5,880), for his planned three-story garment processing plant in the village.

Hu's troubles started in August 2007 when the district government decided to link two roads in order to lay underground pipelines for a sewage treatment plant in the city. Hu's building, unfortunately, stood in the way of the road project.

When the district's urban management and law enforcement bureau started negotiating with him (19 times, according to the bureau) to compensate for the demolition, Hu asked for at least 8 million yuan ($1.17 million), the bureau officials said.

The department, however, believed that the construction cost of each sq m of the building had not crossed 1,000 yuan when it was built, said Zhong Changlin, the bureau's chief.

After repeated negotiations failed, the bureau decided to forcibly dismantle the building, labeling it illegal on the grounds that Hu did not possess a construction permit and that he had failed to obtain proper land use papers from relevant government departments.

The bureau's first demolition attempt was foiled in April this year when Tang, whom Hu had divorced in 2004, threatened suicide.

In the wee hours of the morning of Nov 13, however, Zhong and his men arrived again to demolish the building. But Tang, together with her relatives and those of her ex-husband's, threw rocks and bottles filled with gasoline at them, injuring at least 10 of his squad, Zhong said later.

Nearly three hours into the melee, Tang, who had poured gasoline all over her body, set fire to herself.

The building was dismantled despite the violent suicide. Eight members of Tang's and her ex-husband's family were detained. District officials soon blamed them for "violently blocking the enforcement of law", a charge that they announced at a press conference held last Thursday in the city.

On the contrary, witnesses say, the fully armed demolition squad was the one that violently went about its demolition task.

Before Tang set herself ablaze, she repeatedly asked Zhong's men to withdraw and settle for one more round of talks. Instead, some men broke down doors and, brandishing cudgels, climbed to the top of the building where Tang's relatives hid. The sound of fighting and the cries of women and children could be heard soon after, said Deng Youde, a neighbor.

Wei Jiao, who is married to Tang's nephew, said Zhong's men used cudgels to beat up whomsoever they came across.

"They snatched my one-year-old baby and kicked me several times," she said.

In the mayhem, Tang, who had stayed in the attic, killed herself by igniting the fuel, Deng said.

Tang struggled to survive the blaze, Deng said.

Firefighters tried to douse the flames and Zhong's men admitted her to the Chengdu Military Area General Hospital, where she died on November 29.

"It is the court, not the local government, that has the right to give such (demolition) rulings," Wang Shichuan commented on China Youth Daily.

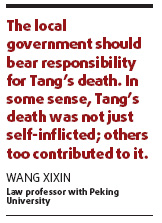

"The local government should bear responsibility for Tang's death," said Wang Xixin, a professor of law at Peking University. "In some sense, Tang's death was not just self-inflicted; others too contributed to it."

"Nearly ten minutes had elapsed after Tang splashed gasoline all over her body and demanded a halt to forcible demolition and more negotiations," said Wang. "However, the dismantling continued despite Tang's desperate warnings."

Under such emergency situations, the government must care more for a person's life, and officials at the scene should have ordered the firemen to spray foam on Tang to thwart such a tragic occurrence, he said.

Even after Tang was admitted into the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of the hospital, no relative was allowed to visit her. The door leading to the ICU was monitored round the clock by four government-deployed guards, said her younger sister, Tang Fuying.

Hu and his son, who had been detained by the police, were allowed to visit Tang only four hours prior to her death, that too, accompanied by government officials and policemen. Their request that other relatives, who were in custody at that time, be allowed to visit her was also turned down, Tang Fuying said.

Such insensitive treatment of private property owners during "forced demolitions" is common, said Wang Cailiang, a Beijing-based lawyer.

A similar incident took place on Nov 27 in Guiyang, in the neighboring Guizhou province.

In a bid to dismantle nine houses and eight shops, a real estate development company entrusted security guards of another company to evacuate the inhabitants by force.

In the wee hours of the morning, the guards came in 10 minivans, smashed the doors and forced 13 inhabitants, who were sleeping, into their vehicles. The residents were gagged and driven away before being dropped in various corners of the city after the demolitions were effected.

In protest, nearly 30 inhabitants blocked four road intersections for two hours using nearly 40 liquefied petroleum gas containers. Nearly 10,000 automobiles were stranded and thousands of people reported late for work, police said.

In another instance, a restaurant owner in Nanjing, capital of Jiangsu province, was forced to wedge in 18,000 iron nails on top of his restaurant building last year to foil a "forced demolition", the website chinanews.com.cn reported.

Wang, the lawyer, and others have questioned the legitimacy of such "forced demolitions". According to Chinese law, only the courts, not government departments, can authorize the use of force for such demolitions.

Jinniu district's urban management and law enforcement bureau had clearly violated the law. Its staff members do not have the right to carry cudgels, which were used to threaten inhabitants during demolitions, said a lawyer surnamed Guo at Zhichengdaohe Lawyers' Office in Beijing, who declined to disclose her maiden name.

The bureau should turn over such cases to the court, which alone has the right to dispatch the police to carry out demolitions as per law, Guo said.

Liu Yajun, another Beijing-based lawyer, said it was incorrect to label Hu's building as illegal as the government departments concerned had found no fault with its owner prior to the district government decision to dismantle it.

Hu went through the proper procedure to register his plant at the local bureau of industry and commerce. He received the business license after the local State land bureau provided documents indicating where his plant would be located. No government department reported it as an illegal construction even though the building had no construction permit, Liu said.

And, the reason Hu's building did not have that permit was because the Urban and Rural Planning Law, which requires permits for all constructions in cities and rural areas, was only enacted in 2007, Professor Wang Xixin told China Daily. Prior to that, no permit was required for the construction of buildings.

"This is a legal loophole," said Professor Wang. "If the Urban and Rural Planning Law is applied now, numerous buildings across the country would be termed illegal."

"The Jinniu district government's decision to label Xu's building as illegal simply because it did not have a construction permit is inappropriate, as there was no such law at the time the building was constructed," he said.

The Jinniu government on Thursday suspended Zhong after the case provoked a massive public backlash.

Professor Wang, however, believes higher officials should be held responsible for Tang's death.

"Only officials at a more senior level, at least the district level, can organize such 'forced demolitions', with not just law enforcement officials, but also firemen and medical staff asked to be at the demolition site," Wang said. "People behind the scenes should take responsibility for the tragedy as well."

Also on Thursday, Ma Xu, chief of the Jinniu district government, said Tang's death was being investigated and those found guilty of breaking the law would be severely penalized.

In an open letter to Li Chuncheng, Party chief of Chengdu, lawyer Wang urged the city's procuratorate to investigate the case and punish the wrongdoers.

He also sought the release of all of Tang's and Hu's relatives, whom he believed were illegally detained.

According to Wang, the Beijing-based lawyer who is known to defend victims of "forced demolitions", there are two key reasons why people forced to give up their properties fight back.

First, authorities acquire land at a lower rate and sell it at a much higher price to developers. This results in resistance from property owners.

"Many local governments rely on land sales to developers to increase their revenues," Wang told China Daily in a telephone interview.

Second, the compensation paid out is relatively lower, and owners cannot use the compensated amount to buy other same-size buildings, the 55-year-old lawyer said.

In the case of the restaurant owner in Nanjing, the developer had promised to pay 15,000 yuan ($2,200) for each sq m, but the cost per sq m had breached the 20,000-yuan mark in the same area.

One way the authorities can solve the problem is by considering public interest first and foremost before planning demolition drives, Wang said.

Professor Wang and other legal experts are planning to submit to the National People's Congress, the country's top legislative body, an amendment to the current Urban Housing Demolition and Relocation Management Regulations. This is aimed at better protecting the interests of property owners, he said.

Under the current regulations, estate developers only need to get from the government the rights to land use before demolishing the buildings upon it. The rights of property owners are, however, not clearly specified. Regulations regarding demolitions must be subject to the Property Law, Professor Wang pointed out.

(China Daily 12/08/2009 page7)