Society

Miners battle lung disease in hazardous mine

By Hu Yongqi (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-02-08 08:15

|

Large Medium Small |

|

||||

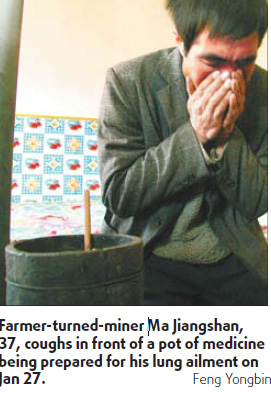

In almost two decades, Ma paid no attention to the damage it was doing to his health. He worked long hours and rarely wore a facemask. He never thought for one second his job could cost him his life.

"If we had been informed about the side effects, I would never have let him go down the mines, even if we did not have enough grain to feed us," said Liu Dongmei, 33, Ma's wife and mother of his four children. "We are at a loss over what to do now."

Ma was one of 304 people from Gulang diagnosed between 2002 and 2005 with pneumoconiosis, or black lung, which is usually caused by years of breathing in dust and smoke. Seven more died of the disease between 1999 and 2009, local villagers said. All of the victims worked in gold mines in nearby Subei county.

Black lung is China's No 1 occupational disease, with about 610,000 registered patients nationwide as of November last year, said Cai Rongta, a professor in labor health and occupational disease at Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, capital of Hubei province.

Almost 80 percent of the 14,000 cases of occupational diseases reported to the Ministry of Health in 2008 were black lung, he said, adding that the disease costs the country an average of about 8 billion yuan ($1.1 billion) every year.

Experts warn that the high number of victims reflects serious flaws in the monitoring of occupational safety across China, and have accused local labor and health authorities of failing to protect workers.

However, most sufferers are concerned about what they will pay for treatment.

Scientists are yet to develop medication that can reverse or totally cure the effects of black lung. A patient's best chance of survival is to undergo surgery to "clean out" the lungs, health experts say. Paying for the procedure, however, is far beyond most farmers' reach.

The lung operation costs about 30,000 yuan, said staff at the Pneumoconiosis Rehabilitation Center in Beidaihe, Hebei province, which is under the National Coal Mine Safety Supervision Department. But the income per capita of farmers in Gulang in 2008 was just 1,980 yuan, almost 50 percent lower than the average for farmers nationwide in 2007.

Ma lives with his wife, children and aging parents-in-law in Miaotai, a remote village at the foot of what locals call Pingding Mountain, an offshoot of the Qilian Mountains that extend to the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. The community has been devastated by black lung.

Although its residents are friendly, Miaotai is a depressing and unwelcoming sight. Its streets are lined with houses built from loess and have thatched roofs, while the air is thick with the odor of cow dung, which residents burn to heat their homes in winter.

|

|

Ma's home has only one electrical item: a 1970s radio, which sits on a table covered with a sheet of red cloth.

Families here have struggled to make a living for generations. The area is often hit by drought and suffers a chronic water shortage. Although farmers toil mercilessly in the fields, their harvests are reliant on summer rainfall and do not always meet demand.

"We have no choice but to travel to Subei to work in the mines," said villager Liu Zhongxi, 42. "We need the money, so all we can do was bear the dusty and dark conditions."

Ma developed a cough in 1989 but did not go to see a doctor until 2002, when he began struggling for breath and had severe chest pains. Tests at Wuwei People's Hospital showed he has black lung. He had surgery to clean his lungs in 2005 at the No 1 Hospital affiliated to Lanzhou University, but the treatment failed to cure him. He is now unable to work on his land or around the house, and takes only traditional Chinese medicine to alleviate his crippling symptoms.

The father-of-four was the first of the 304 Gulang residents diagnosed with black lung. County officials have since arranged for more villagers to undergo tests in Wuwei, the administering city, but the results are still to be announced.