Society

'Work widows' suffer in silence

By Hu Yongqi in Pingliang, Gansu, and Peng Yining in Beijing (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-03-08 07:38

|

Large Medium Small |

Liu Xiaoling, 24, lives with her 18-month-old son and mother-in-law in Huangwei town, Anhui province. She used to work in the same factory in Shenzhen, an industrial hub in Guangdong province, with her husband Du Ping, 28, but had to return home in 2008 when work dried up due to the financial crisis.

Although her mother-in-law is on hand to help with little Ao Xing - his name is the same as the "Olympic Games" as he was born during the Beijing event - Liu said she still feels unable to cope alone.

"I feel terribly lonely when my husband is away. He can only call home twice a month and I cannot stop thinking about him," she said. "He came back for Spring Festival but he was only here for eight days. I will not see him again for the rest of the year."

|

||||

"Living apart has changed people's attitudes about adultery," said researcher Jiang. "In the past, having an affair was an unforgivable sin in rural areas but people are starting to accept it. Most of these women have no choice but accept it, although the betrayal only aggravates their depression."

Left-behind women are also more vulnerable to unexpected events such as natural disasters and disputes with neighbors, said professor Ye.

"When their husbands go away, their wives' ability to conquer dangers is greatly reduced. Elderly people, women and children are naturally more disadvantaged in such situations," he said. "Almost 40 percent of the women I talked to feel scared when their husbands leave."

Ma Caixia, 39, was alone at home with her two children when their home - a cave 10 meters underground in Damaigou - was rocked by the massive 8.0-magnitude earthquake in May, 2008.

"The windows smashed and the front door was shaking," she said, whose children are 18 and 20. "My children were terrified and I had to push them out of the cave. If I hadn't, we would have been crushed."

Her husband, 40-year-old Yue Junqiang (no relation to Yue Shuangbao) was working down a mine in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region while his wife and children were fleeing their collapsed home. "I was distraught when I heard how they had to escape the earthquake," he said. "I do worry about their safety but what can I do? If I stay at home, my family will have to starve."

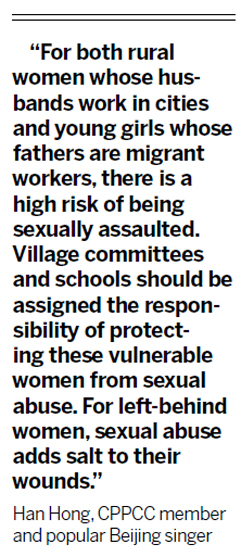

"Work widows" are also vulnerable to sexual predators, said Ye. Media reports have exposed several cases of men who stalk women with husbands working in other provinces, including Du Fenghua, 43, who was convicted of raping 10 women in Yunnan province.

To prevent potential problems, more migrant workers are now taking their family with them to the cities.

Mao Jianping, 31, who comes from Pingliang's Kongtong district, travels to work in Guangzhou every year with his wife Duan Guilian and 1-year-old daughter Mao Yuting. "There are always dangers and problems when I leave my wife and daughter at home so I take them with me. This way, at least we are all together."

However, this option is far more expensive, with prices of such things as school fees much higher in cities than in the countryside.

"The city's development depends on migrant workers but they still don't provide them with enough resources to keep a family," said Jiang Yongping. "This instability impacts women more than men as they probably end up being the ones left behind."

|

|

|

Mao Longfeng, 25, whose husband is a migrant worker, helps dress her son, He Tianxi, in Pingliang, Gansu. FENG YONGBIN/CHINA DAILY |