Society

Ancient crafts may end up art of the past

By Zhang Yuchen in Beijing (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-03-26 06:57

|

Large Medium Small |

City of culture

|

Master Li Xiaohong paints a snuff bottle. There are more than 1,800 recognized traditional Chinese handicrafts. [DU LIANYI/ FOR CHINA DAILY] |

Beijing alone once had more than 1,500 varieties of handicrafts, or wanyi'er, ranging from ancient weapons to elaborate decorations, said Bai Dacheng, who makes bristle figurines and is one of only about 40 traditional toymakers left in Beijing.

Authorities started work to preserve the city's ancient arts in 2002 and, 12 months later, set up Baigongfang.

Based in a three-floor building in Beijing's Chongwen district, Baigongfang has gathered together 33 masters of varying disciplines, and provides them space to make, teach and sell their traditional crafts. However, the project has not received a penny from the local government since 2006, said its vice-director Zhang Xinchao.

Every year, Baigongfang applies for special funding from the Beijing Arts and Crafts Association, but "we have found it harder and harder to get money", he said. "As it shifted its priorities, the association has adjusted its plans to help other projects. We can understand that. Traditional skills are just one aspect of culture and there are many other projects in need of money."

Beijing Arts and Crafts Association did not reply to messages left by China Daily.

Liu Xing, 36, and 41-year-old Liu Yu are both sons of Xing Lanxiang, a master of liuli, a type of glazed Chinese glassware. They took a risk by quitting well-paying jobs to open a store in Baigongfang in 2004. Today, the venture makes about 1,000 yuan ($140) a month, barely enough to cover their running costs.

"All we can do is hope that we stay fit because if either of us falls ill we won't be able to pay the medical costs," said Liu Xing, who used to be a driving instructor. He said his wife has had to find a job to support the family. "Half our energies are wasted on thinking about how to earn extra money. We have no time to improve our skills," added Liu Yu, who used to work at a Jeep factory in Beijing.

There are thousands of varieties of Chinese glassware but the brothers have mastered only a few hundred, while some are no longer practiced due to a lack of suitable facilities and materials.

Picking up a jade-like glazed lion, Liu Xing explained that to make the ornament the glass needs to be melted in an extremely hot fire. "There are no factories around today that would let us use their furnaces," he said. "This lion was made only because former premier Zhou Enlai ordered an aircraft factory to help my mother and her fellow masters in 1958. That's why few want a full-time job protecting and transferring their family skills. It's not a promising future."

|

Above: The courtyard of Baigongfang in Chongwen district, where 33 masters of varying skills can make, teach and sell their traditional crafts. Below: Yao Fuying, 67, who is retiring from embroidery after more than fi ve decades. He once had 10 apprentices. [ZHANG YUCHEN - YANG SHIZHONG / CHINA DAILY]  |

The corridor outside the brothers' glass store was crammed with people when Baigongfang first opened. Today, there are often empty.

Baigongfang helps promote traditional handicrafts with exhibitions and fairs. However, they are usually held far from the city's prosperous central areas, said a craftsman who did not want to be named. Zhang Chang, who makes clay figurines, said he earned just 70 yuan a day at a temple fair organized in 2008.

Although retired, as a municipal-level master, 65-year-old Xing Lanxiang receives a monthly stipend of 200 yuan a month. Masters recognized at the State level get between 400 and 800 yuan, said Hang Jian, deputy dean of Tsinghua University's academy of art and design and member of the National Experts Committee for Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection.

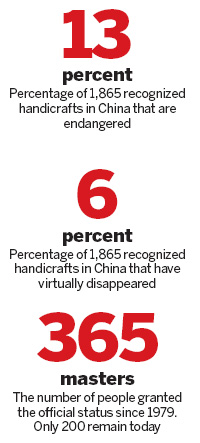

Since 1979, China has granted "master" status to 365 people. Today, only 200 remain. The stipend, which has not been increased since the 1980s, is paid only to those with two apprentices, he said.

The masters who moved into Baigongfang have gradually started to leave again over the last three years, said Liu Xing. A store owner who did not want to be identified said that, because of its remote location and the fact it was not properly promoted, few shoppers know about Baigongfang.

Promoting skills

China's intangible cultural heritage protection was launched in 2005. Since then, the central government has released a list of about 1,000 cultural skills under threat and appointed 1,488 intangible cultural heritage "representatives", such as Xing Lanxiang, who experts say receive a grant of about 8,000 yuan a year.

However, before applying for a representative role, Liu Xing said Chongwen district authorities promised to promote her mother's business and give her 200,000 yuan if she was successful.

Yang Jianye, the director of the district's office of intangible cultural heritage, said all masters are offered a cash reward but are asked to sign a contract securing their services in the future to collect the money.

"Applying for intangible cultural heritage has become like a campaign," said Hang at Tsinghua University. "It's nothing but a vanity project. Governments see heritage as a way of developing the local economy. They have little intention of actually protecting traditional skills or customs."

Although China began to protect its intangible cultural heritage about 50 years behind other Asian nations, such as Japan and South Korea, "the government has made great efforts to push it forward", said crafts expert Tang Shukun.

As grassroots demand is shrinking, experts say traditional handicrafts need to be better promoted. "It should be the strategy to not only protect culture but also promote it well," said Hang. "The more craftworks that are bought, the faster the skills progress. Otherwise a skill just gradually dies out."

Yao Fuying, the master embroiderer, said that although people are buying less, he has not given up hope on the public's desire to protect traditional arts and crafts. "Visitors who come to see my work show great interest, especially the young people, who always ask about whether the work is handmade. They do care about it," he said, as he continued to stitch while listening to his favorite composer, Mozart.

"Each work of handicraft has its own soul that reflects its maker's unique outlook on life and art," added author Chen. "These crafts are in the cultural genes of a people. But when the DNA of a people changes, how can the things around them stay the same?"

Wen Yi contributed to the story