Society

Blood screening to be tightened

By Shan Juan in Beijing and Hu Yongqi in Hubei (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-05-13 08:12

|

Large Medium Small |

In short supply

Health experts also raised serious concerns about the shortfall in donations of blood plasma nationwide and the effect it is having on the manufacture of drugs.

Rural residents are typically the source for the vast majority of supplies in both. Although traditionally Chinese are reluctant to give blood because they see it as damaging their body's integrity, villagers are often swayed by the money collection centers offer for donations.

But as more farmers have flocked to major cities, where they earn larger wages and have fewer opportunities to give blood, stocks have plummeted.

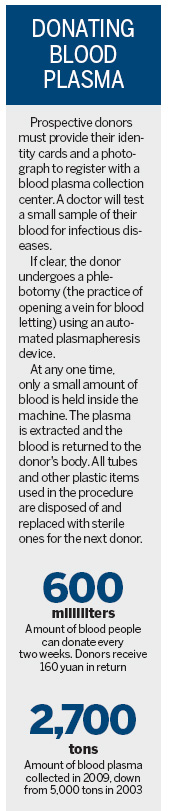

At a plasma collection center in Yunxian, an impoverished county in Hubei province that produces many migrant workers, donors can visit once every two weeks to give 600 milliliters for 160 yuan. Yet the number of regular clients has almost halved in the last five years, according to Li Yongcheng, who has run the clinic since 1998.

"We used to get 10,000 donors, now we get just over 6,000," said Li, who is also the former deputy director of county's health bureau.

In an overhaul of plasma collection services in 2004, the Ministry of Health closed 262 donation centers, leaving only 138 in operation. This resulted in the plasma donations falling from 5,000 tons in 2003 to 2,700 tons last year.

The Yunxian center alone today extracts only 30 tons of blood plasma a year, two-thirds its total in 2003.

"(Selling plasma) is good for my family but I don't know what they do with the plasma after they take it from me," said Yang Jinju, 36, a villager from Daliu township who sat in the clinic's waiting room.

Like Yang, few realize that the plasma is sold to medical firms to be used in the manufacture of drugs that retail for more than 600 yuan per milliliter. The plasma collected in Yunxian is shipped to Wuhan Institute of Biologic Products, which makes albumen and blood coagulation factor 8 to treat hemophilia (a condition that stops blood from naturally clotting).

"Our institute was designed to manufacture 300 tons," said Yang Xiaoming, president of the institute. "But owing to shortage of plasma, we can only fulfill half of our production capacity."

In China, about 100,000 people suffer hemophilia, which can prove fatal in the event of an accident. However, a China Daily check at several major hospitals in Beijing, including Tongren Hospital, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Friendship Hospital and several clinics affiliated with Peking University, showed that not one had albumen or Blood Coagulation Factor 8 in stock, nor could they tell patients where to buy either of them.

"Every time when I bleed, my mother is horribly stressed," said Liang Zhenyu, 28, a hemophiliac living in Beijing's Haidian district. His family has struggled to find the medicine he needs in the capital and, to keep him safe, have banned him from leaving the house alone. "My mother is afraid that some day I will die without the medicine."

Sun Jing, a specialist in hemophilia at Guangzhou Nanfang Hospital in Guangdong province, blamed the dangerous shortage in the necessary drugs on the inadequate plasma supply. "The government has attached a lot of importance to plasma security but not enough to supply," he said.

The high demand and low supply has spawned a black market for the drugs, with some crooks offering counterfeits for sale. In December last year, two men called Li and Dou were arrested in Jinan, capital of Shandong province, for selling fake albumen to top hospitals in 20 cities.

"The fake albumen would probably kill me instead of saving my life," said a hemophilic patient surnamed Hu in Changping district of Beijing.

Importing plasma drugs, however, would likely make treatment far more expensive. Customers pay 609 yuan for 250 grams of albumen made by Shanghai Raas but would have to pay more than 1,300 yuan for albumen shipped from overseas.