The spread of sand in Xinjiang stops, and a major road to Urumqi is saved.

|

|

The 562-kilometer road connecting Urumqi and Hotan, which once was plagued by problems caused by the sand, now has desert plants as protection. [Photo/Provided to China Daily] |

For 2,000 years, people have battled the relentless wind and sand of the unforgiving Taklimakan Desert.

Ancient civilizations along the Silk Road were swept aside, leaving traces of their existence only in the remains of temples and frescos.

Qira county in the southwest of the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region is one of the most severely hit regions.

Without scientific methods to combat desertification, the march of the sands of time would have continued.

But scientists have found an oasis of triumph after three decades.

Read more

Scientists make land arable again

| The beauty of drought-enduring plants |

|

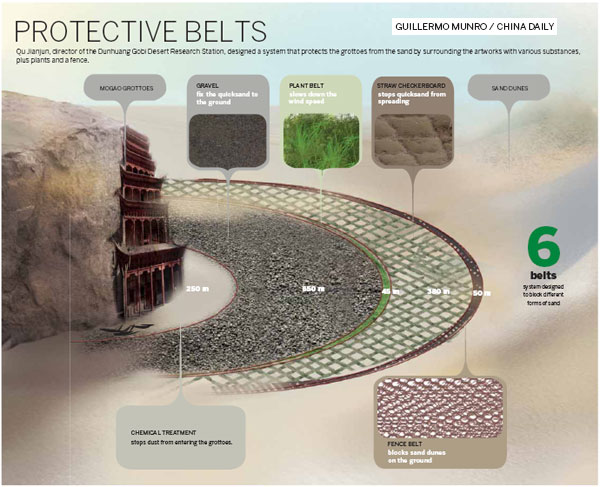

Grotto artworks saved by system of protective nets In AD 366, a Buddhist monk had a vision on the outskirts of Dunhuang, a bustling area on the Silk Road. Thousands of golden lights conjured up an image of a thousand Buddhas. The vision inspired him to build a cave. This, according to legend, was the beginning of the Mogao Grottoes of Dunhuang. |

|

|

|

Driver's expertise plays crucial role in scientific research It is not just the elements that scientists have to guard against when conducting research in the desert. The unrelenting sun and sand-blown days and nights can make any desert work an uncomfortable experience. On top of this, predators sometimes prowl. |

Graduate student has assignment in underground station Li Shoujuan, 26, has a lonely and sometimes dangerous job. From April to October, 9 am to 9 pm, Li, a researcher in the Gurbantunggut Desert, monitors an electronic screen buried deep into the scorching earth. |

| Animals living in the desert |