Lighting the way to a brighter future

By Li Yang (China Daily) Updated: 2016-06-14 07:50

|

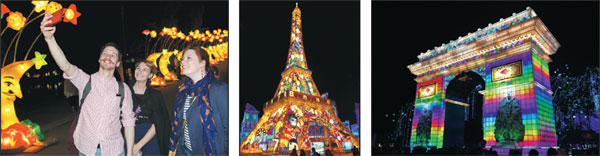

The lantern show in Zigong, from January to March, attracted a large number of visitors. [Photo/Wei Xiaohao / China Daily] |

After its traditional salt-extraction industry died out, a small town in Southwest China set its sights on becoming the world capital for Chinese lanterns. Li Yang reports from Zigong, Sichuan province.

'My grandpa sneers at today's lanterns. When he saw the annual lantern show in Zigong three years ago, he blurted out: 'Do you call those things lanterns?' " Yang Shiping said, with a laugh.

Yang is a third-generation lantern maker in Zigong, a city in the southwestern province of Sichuan. Known nationally as the "salt city", Zigong was a center of salt extraction for more than 2,000 years. Once, it supplied one-third of all the salt consumed in China, before cheaper sea and lake salts became more popular.

The industry nurtured many businesses, including lantern making. Yang's grandfather Yang Quansheng, now in his 90s, started making lanterns in the 1920s, when he worked as an apprentice for several wealthy "salt families" who displayed the lanterns at an annual festival. Winning the champion's ribbon was an indication of power and status.

Some of the lanterns displayed in the annual show are produced by Yang's factory, the Huilongtang Culture and Art Company, which was founded in 2012.

Bamboo, paper, silk, hemp rope, scissors, knives and candles were all Yang Quansheng needed to make a lantern. Now his grandson, a fine arts graduate, uses a computer, light machinery, energy-saving bulbs, steel and chemical fibers. His factory employs dozens of workers, who are divided into three groups: artistic innovation, machinery and general assembly.

Seeking new inspiration

"The biggest change has been in ideas," he said. "Grandpa is familiar with all the old legends and traditional stories that were the main source of creative ideas for the old lantern makers. But I must seek inspiration from a wider range of sources to cater to customers from around the world."

The company sells its lanterns in Europe, North America, Asia and Oceania, and its annual sales revenue is about 20 million yuan ($3 million).

Zigong is home to more than 400 lantern companies, and more than 70,000 of the city's 400,000 residents work in them. Their lanterns are shown in 500 major cities around the world, and the combined annual revenue is about 10 billion yuan, according to Liu Yongxiang, Zigong's mayor.

The government has identified the lantern industry as an important driver of the city's economy. The modern annual lantern show, held in a downtown park, is listed as a part of the nation's intangible cultural heritage. It has been held in the first two months of the lunar calendar every year since 1964, although it was suspended during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76). The event attracts more than 2 million visitors from home and abroad, and generates about 7 billion yuan in tourism revenue every year.

"Many people did not expect an 'entertainment' business to become a pillar industry after Zigong's salt lost its competitiveness," said Cheng Longgang, a historian and deputy director of the city's salt museum. "The proportion of lantern workers in the local population is already comparable to that of salt workers during the peak of the trade," he said.

"Likewise, 'salt-gang food' - pickled beef or vegetables that were given to long-distance drivers in the salt industry - is a unique Zigong attraction that gained a reputation nationwide, even though the salt gang disappeared long ago."

A dying art

When he was a child, Yang, 35, did not want to be a lantern maker. His father, who learned the trade in the 1970s, suggested that he should become a farmer instead, because the salt industry was in decline and the powerful families disappeared when the government acquired all the private businesses in the early 1950s, which led local people to regard lantern making as a dying art.

In the mid 1960s, the central government relocated 22 State-owned enterprises, two institutes and a college to Zigong. The city was developed into a salt-related base for the chemicals industry during the "third-tier construction" campaign, a wave of industrial construction in remote inland areas designed to protect factories in the event of war.

During winter and spring, Yang Quansheng, the grandfather, worked as a lantern maker for local enterprises and supplemented his income by farming for the rest of the year. During the market reforms of the 1990s, many of the businesses, which relied on government support in the planned economy, went bankrupt or were relocated to Deyang, an industrial town near Chengdu, the provincial capital.

"The late 1990s was the most difficult time for my family," Yang Shiping recalled. "After seeing some of the artisans go to the coastal cities to help make lanterns, I felt it was time I embraced my family legacy and started running my own factory."

Learning hard lessons

Many lantern-making families had similar experiences. In 2008, when they began to export their goods or organize exhibitions overseas, the international market posed many challenges for the old family and workshop business models. Almost every lantern enterprise paid a "tuition fee" when the government encouraged them to export their goods via the "going out" policy.

The memory of his first disastrous overseas operation - an exhibition in a small town in southern Germany - is still fresh in the mind of Zhong Dongquan, general manager of the Zhongyi Lantern Company.

"I lost 4 million yuan through poor publicity, a lack of understanding of German culture and bad weather. There was no support from the local government," he said. "I only calculated how many people lived within an hours' drive of the town, but the show was staged during the rainy season and the visitors didn't seem interested in traditional Chinese lanterns."

Zhong learned several lessons from that initial failure; he became more prudent in choosing locations, studied local people's interests carefully and paid special attention to communicating with local governments.

That attention to detail has paid dividends and Zhongyi Lantern now has annual revenue of about 90 million yuan, with more than 80 percent generated via exports.

To explain why he focuses on the overseas market, Zhong pointed out that although the Chinese market is big, some companies always try to secure orders by cutting prices, which is not good for the healthy development of the industry.

"Zigong's lantern makers should continue the industry's fine, historic traditions. The old lantern makers built their competitiveness on innovation, skill and cooperation. Those old qualities still work well today," he said.

In 2012, a guild of lantern enterprises was established, and the city government is building the world's first lantern industry park.

Li Zhongwen, general manager of VYA Creative Lanterns, which started organizing exhibitions overseas in the late 1990s, said the guild and the government should work more closely to regulate the development of the industry.

Government support needed

"The long-term prosperity of Zigong's salt industry could not survive without the strong discipline of the business families, constant technological innovation and the support of the government. That applies to the lantern industry as well," he said.

Li thinks the implementation of the Belt and Road strategy, proposed by President Xi Jinping to promote common development and industrial cooperation, would provide a golden opportunity for the city's lantern makers to expand their business opportunities overseas.

Statistics from the Zigong government show that the city's exports of cultural products, a large share of which is held by lantern-related businesses, earned more than $13 million last year, a rise of about 56 percent from the year before. About 80 percent of the lanterns China exported last year came from Zigong.

"The Chinese lantern is an ideal symbol of culture and an auspicious messenger for good wishes and goodwill," Li said, adding that he is hoping to transform the lantern show into a year-round Disneyland-style theme park, rather than just an annual event in the wake of the Spring Festival holiday.

The consensus among lantern makers is that Zigong's strength lies in its talent, innovation, technology and experience of organizing lantern shows. However, the problem is that many of the raw materials are manufactured in the distant coastal regions.

"Zigong should build an industrial park, and also draft industry standards and take steps to protect intellectual property rights as soon as possible," Zhong said.

Greater industrialization will also require training programs to be standardized to break away from the old master-apprentice approach.

Since 2012, a vocational school in the city's Da'an district has offered China's only training program for lantern-makers. The students learn history, traditional fine arts, paper cutting, design, welding and how to organize an exhibition.

"Most of the skilled workers are in their 40s and 50s. More than 600 graduates are working in about 30 lantern companies in Zigong - they are the fresh blood in an old industry," said Wang Jian, the school's deputy principal.

Contact the writer at liyang@chinadaily.com.cn

Brine, bamboo and business

Today, Shenhai Well is the only brine well in downtown Zigong that still produces salt by the old methods. Nowadays, it's just a tourist attraction.

Although work started in 1835, it took 30 years to drill the 1,001-meter-deep well, which produced 8,000 cubic meters of natural gas and about 14 metric tons of salt a day during its peak period. Now, output has dwindled to about 3,000 cubic meters of gas and 2 tons of salt a day.

The local people invented the classic methods of percussion drilling and brine extraction. The drilling tools mostly consisted of rope, a bamboo shaft and an iron bit. Cattle were the main power source for the drilling and retrieval work. The borehole was about 15 centimeters in diameter and hundreds of meters deep. During the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), the Shenhai Well had already reached a depth of 300 meters.

The brine is retrieved via bamboo tubes fitted with membrane valves that prevent the liquid from slipping down the tube, and is piped into flat pans for boiling. The natural gas liberated by the drilling process is used as the energy source. A small amount of water is added along with crushed yellow soybeans to absorb the impurities in the salt during boiling. A yellow layer forms during boiling, but it is scraped off to reveal the pure salt underneath.

There were once 198 wells in the 1.2-square-km around the Shenhai Well. The wooden derricks, which stood about 20 meters high, resembled anti-aircraft guns, which resulted in the area becoming a target for Japanese bombers during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-45).

In fact, conflict played an important role in the development of Zigong's salt industry. During the Taiping Rebellion (1850-64) and the war, when the salt production bases in East China were occupied, Zigong became the country's main supplier, and a salt tax became a reliable source of government revenues to subsidize the army.

Its strategic importance during the war saw Zigong, formerly known as Fushun county, become a city in 1939 with the approval of the central government. The name derives from the names of two nearby older wells, called Ziliu and Gong.

In the 1870s, investment by entrepreneurs from Shaanxi province saw Zigong's salt industry and trade reach its peak with more than 700 salt wells producing about 200,000 tons a year.

Four big families - called Wang, Li, Hu and Yan - who prospered during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) were the main employers of the city's lantern makers.

In the 1950s, the government merged all the private salt businesses into five State-owned factories, which used modern vacuum salt-production technology and employed about 50,000 local residents. However, all five factories had collapsed by 2005, undercut by sea and lake salt, which were three times cheaper to produce.

In 1959, the Shaanxi Businesspeople's Club, built in the mid-18th century, became China's first salt museum. It's a must-see tourist attraction, along with Xianshi town, a well-preserved ancient salt port and market southeast of Zigong that was active from the 11th century until the early part of the last century.

|

From left: Visitors take a selfie at a Chinese lantern festival in Budapest, Hungary, which featured 45 artworks from Zigong, Sichuan province. Lantern versions of the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe were highlights of the annual international lantern show in Zigong, which ended in March. [Photos Provided By Xinhua And Li Yang / China Daily] |

|

Zigong, pictured in the 1990s. |

- Budapest zoo hosts Chinese lantern festival

- Fire Lantern Festival celebrated in Hunan

- Lantern show raises awareness of China through art in Colombia

- Travel after the Lantern Festival more affordable

- Karamay integrates modern technology and tradition for Lantern Festival

- Family celebrates Lantern Festival hundreds of miles apart

- Villagers perform Yangko in NW China to mark Lantern Festival

- Xi's visit set to boost Belt, Road projects

- Country braces for onslaught of major storms

- High-res satellite to help monitor floods, pollution

- Homemade bombs hurt four at Shanghai airport

- China pushes for market economy status

- Employment preferences of college graduates changing

- Top political advisor meets mainland-based young Taiwan entrepreneurs

- Incubation platform for Taiwan start-ups launched in Xiamen

- Oxford Dictionary among Top 10 most disliked textbooks

- World heritage site opens to public in Central China