Lost letters help to heal old wounds

|

After more than six decades, Shang Yuanmei (left), 93, receives her husband's letter at her home in Lishui, Zhejiang province, delivered by Chen Jingtao (right), a member of staff at the Jilin Provincial Archives.Provided By Jilin Provincial Archives |

Messages written at the height of a crucial siege are finally arriving at the homes of their intended recipients, six decades after the end of China's civil war. Zhao Xu and Liu Ce report from Shenyang.

"I dreamed of you last night, reclining against my chest ... only to wake to the incessant rain beating on the window. Frogs are croaking nonstop. Deep inside, I feel a sudden invasion of loneliness, a loneliness that disrupts my peace of mind ..."

Those words were written by Liang Zhenfen, a veteran soldier with the Chinese Nationalist Army, on the night of June 3, 1948, during the siege of Changchun, capital of Jilin province and a Nationalist stronghold. It was two years into the civil war between the Nationalists and the Communists, and barely four weeks since the Communists had laid siege to the city in Northeast China.

The letter was sealed in an envelope stamped with multiple seals and the words "Air-Mail", in English. It should have traveled 2,900 km to Guangzhou, Guangdong province, and landed in the hands of Huang Guantang, Liang's girlfriend, who he had nicknamed Bi, meaning "Jadeite".

It never arrived. Instead, 62 years later, in early 2010, a copy was handed to Liang by his longtime carer, Li Bei, who had just returned to Guangzhou, Liang's home, from the Jilin Provincial Archives in Changchun, where the letter is kept along with 1,396 others written by Nationalist soldiers stationed in the city from May to October 1948.

Wang Man, director of the archive's material collection office, said she could hardly imagine the depth of emotion in the letters, until she leafed carefully through the dried-out, yellowed pages.

"The vertical lines-Chinese used to be written vertically, from right to left-are powerfully evocative," she said. "The rustling sound made by the turning of the pages reminded me of a river, the river of history which once flooded, rather ruthlessly, over these young lives."

Personal details

In May 1948, a 100,000-strong Communist force advanced to the outskirts of Changchun and laid siege to the city, which contained 100,000 Nationalist soldiers and hundreds of thousands of local residents. The siege lasted until mid-October, when some of the Nationalist soldiers revolted and the last defenses collapsed.

"What is mentioned briefly in high school history books is recounted in bristling detail in the letters, which also contain personal photographs, awards certificates and money orders," Wang said.

Since 2010, the archive has been searching for the owners, including senders and recipients, and their offspring. "We give them high-quality copies - the real letters stay in the archive permanently," she said. "By doing this, we intend to shed more light on these precious materials and offer solace to wounded souls."

Last year, the archive joined with Netease, a leading Chinese internet company, to get the message out. So far, the owners of about 40 letters have been traced across 10 provinces.

The circumstances under which some of the letters were written are likely to remain mysteries. One was written on June 11, 1948, by Yang Yanting, a field doctor with the Nationalist Army, to his mother. He recalled childhood events, and tried to "peer towards my hometown in the far southwest, but the view was clouded by dark plumes of smoke from another round of bombing."

The Communists had already taken control of Dafangshen Airport, on the city's northwestern fringe, which effectively cut off air traffic between Changchun and Shenyang, capital of Liaoning province, the nearest Nationalist stronghold, 300 km away. Even though no letters could be sent, the increasingly desperate Nationalist troops still wrote them.

Soybeans and suffering

The bombing campaign continued, in part to prevent Nationalist airplanes from dropping supplies. The result was "a winter scene" depicted by Jilin Daily on July 23, 1948: "In the city park, the trees are largely leafless ... those that still had some left saw their branches bent to the weight of a few hungry gentlemen."

In a recent interview, Zuo Lichun, a self-professed "old Changchun hand", said that during the siege his mouth became "a soybean milk machine".

"Our whole family would only get up after dark - that's when my mother reached for a small bag of soybeans. Each one of us got a few-no more than 10 I think. After chewing until there was nothing left, we curled up in bed and closed our eyes," the 86-year-old recalled.

Zuo saw the body of an elderly woman in the street: "I dared not to go up and look. A passer-by said, 'she's dead'. Money wasn't worth anything: a big sack of banknotes was not enough to buy one shallow scoop of rice, and people with gold bullion traded it for a block of wine lees."

Zuo is one of about 70 people connected with the siege who have been interviewed by Qiao Huibo, from the Jilin archive.

One of them is Shang Yuanmei, 93, the intended recipient of a letter written by her husband, Zheng Zhida, a Nationalist soldier, in June, 1948.

The last time they had seen each other was in 1944, when Zheng's regiment passed their home in Zhejiang province, and it would be more than four decades before they met again.

"My grandpa fled Changchun during the siege, and left for Taiwan before 1949," Shang Xiaowan said. Her mother was the veteran's only daughter with Shang Yuanmei.

"When grandpa returned in the 1980s, he was with fellow veterans who had just been granted permission to visit the mainland. My mother recognized him instantly because she looked just like him."

Qiao gave the replica letter to Shang Yuanmei in August last year, three years after Zheng died in Taiwan at the age of 91.

"Initially she showed no emotion. Yet when she started to trace the lines of familiar writing with her fingers, her lips began to tremble. The shore of her memory, which must be littered with wreckage from the past, was being flooded once again," the 38-year-old said.

Escape

By comparison, 86-year-old Ma Yulan was lucky: her 93-year-old husband, Chen Yixiu, gave her a comforting pat on the back as she haltingly told the story of her escape.

"I left my woolen coat - my only valuable possession - with a man who got me and my infant daughter out through his associates in the Communist army," she said. "I had to part with the coat, anyway. Someone told me that looking like the wife of a Nationalist officer would do me no good. That was just a few weeks before the siege started."

In January, 1948, Ma gave birth to a daughter in Changchun, while her husband, a Nationalist army doctor, was stationed in Shenyang. "I remember walking to one of the checkpoints on the city border, baby in arms. There, people were piling up, all wanting desperately to get out," she said. She and her husband were later reunited in Shenyang.

In early 1946, Nationalist troops were sent to Northeast China, where fierce battles were about to break out between them and the Communists. Chen was stationed in Shenyang, as part of the 50th division of the New First Army of the Nationalist Army. At the same time, Liang Zhenfen's 38th division merged with other forces to form the New Seventh Army - the main force defending Changchun.

War of attrition

Chen Jingtao, 43, joined the archives in 2009. Having met several letter writers and recipients, he rejects criticism of the Communist's tactics.

"There were casualties - no doubt about that. But if fighting had broken out, there would probably have been many more deaths," he said. "At the beginning, no one, including locals, was allowed out by the besiegers. This is understandable from a military point of view, since the siege was designed to bring the Nationalist troops to their knees, mainly by cutting off their food supply. Letting people out would have lengthened the process, and possibly allowed spies to escape."

However, during the middle and latter stages of the siege, when starvation gripped the city, the checkpoints were opened a number of times to let people out.

"Those who left were treated very well. A few years ago, a Communist soldier who participated in the siege told me that they prepared rice soup for the 'newcomers' - soup because the people had been starving for so long that their stomach walls had become extremely thin and inelastic," he said.

Qiao's grandmother lost two of her three young children, including a newborn son, to starvation, before she managed to flee the siege with her surviving child. Later, she had six more children, including Qiao's father.

Friends and enemies

Among the besiegers was Li Zuyao, the father of Li Bei, who has cared for Liang, the veteran, for the past eight years.

"Liang was interviewed in a documentary I watched about the siege in 2008," the 55-year-old Guangzhou resident said. "Before his death in 2005, my father's stories offered me glimpses of that history. What did his former enemy have to say? I wondered, and knocked on the door."

It was the start of a caring relationship. Li Bei said she rediscovered the father who had left her, while Liang found the daughter he never had.

"My father and Liang are so similar. Both had excellent recall and were avid map readers, with keen interests in geography and history," Li Bei said.

On April 5, 2006, Liang visited the New First Army Memorial in Guangzhou. The memorial was built by the Nationalists between 1945 and 1947 to commemorate those who had fought and fallen in the China-Burma-India Theater, which saw some of the bitterest fighting of World War II.

There, he befriended Yan Weiquan, a WWII historian whose father-in-law was a New First Army general. In 2009, Yan undertook research at the Jilin archive. "I came across a book published by the archive a few years earlier which consists of more than 100 letters. Liang's was among them."

When Li Bei handed Liang a copy of the letter, the old soldier simply smiled bashfully. Bi died in 1995, and the last time they saw each other was in the early 1980s.

"Liang was captured at the end of the siege, but was released in 1954," Li Bei said. "He returned to Guangzhou, but refused to marry Bi, fearing that more upheaval was about to come."

Bi moved to the mountainous province of Guizhou, nearly 1,500 km from Guangzhou, where she had a daughter. In August last year, Liang met Bi's daughter for the first time. "She gave him a photo of her mother, the only one the old man ever had," Li Bei said.

Liang had written "No 316" on the envelope of the letter. "That means it was the 316th letter he had written to her (Bi) since he left Guangzhou in the spring of 1946," Li said. "It was also the last he wrote to her, and the only one known to still exist."

Following their breakup in the 1950s, Bi burned the letters Liang had sent her.

The last visit

In 2009, Zheng, the former Nationalist soldier, returned to the mainland for the last time.

"Over the years, my grandfather returned more than 20 times, despite the fact that he had married in Taiwan. He couldn't forget my grandma," Shang Xiaowan said

Shang Yuanmei's memory is increasingly frail, yet every day, the 93-year-old picks up the replica letter and gazes at the promise her 27-year-old husband made all those years ago: "I will be back very soon."

Han Junhong contributed to the story.

|

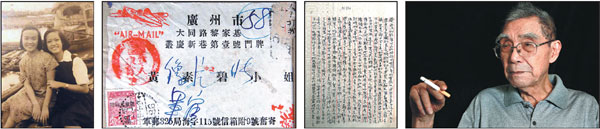

Left: An undated photo of Huang Guantang (left) and a friend. Center: The letter written in 1948 by Liang Zhenfen to Huang, his girlfriend at the time, was sealed in an envelope with the words “AirMail”in English. Right: Liang Zhenfen, a former soldier with the Chinese Nationalist Army.Photos Provided By Jilin Provincial Archives And Jiang Hui / For China Daily |

|

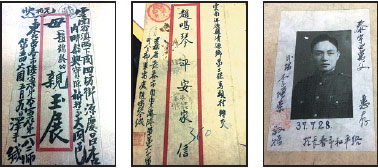

Some of the letters written by Nationalist soldiers during the siege of Changchun, Jilin province, in 1948.Provided By Jilin Provincial Archives |