Plants sew the fabric of change in Xinjiang

|

|

A worker fixes a thread on the production line at Huafu Top Dyed Melange Yarn Co in Aksu, a southern city in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. Photo By Zhu Xingxin / China Daily |

Efforts to grow textile industry and attract startups are providing employment for impoverished ethnic communities. Cao Yin reports from Aksu, Xinjiang.

Nurgul Islam removed the white face mask covering her mouth and wiped the sweat from her eyes. "I used to be anxious about the future," she shouted as banks of sewing machines roared around her, "but this job has set me free."

The 21-year-old works in quality control for Ke Ning Textile Technology Co's sock factory in Aksu, a city in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region.

Before she was hired last year, Islam said she felt lost. "I had nothing to do, and I didn't know what I could do." She had not long graduated from an Aksu vocational school with a certificate in kindergarten teaching, yet she had no desire to return to her native Kartal, an impoverished township more than 50 kilometers away.

Fortunately, she was recruited by Ke Ning through a cooperation agreement Kartal signed with the city's textile enterprises. "Now I'm paid 3,500 yuan ($520) a month, and I see hope in the plant, which I couldn't in my village," she said.

Xinjiang produces more than 60 percent of China's commercial cotton, and Aksu is one of the biggest cultivation areas. In 2010, the city established the Textile Industrial Center, where 64 enterprises from across China have opened production lines, not only to to save on labor costs, but to create job opportunities for the region's ethnic groups.

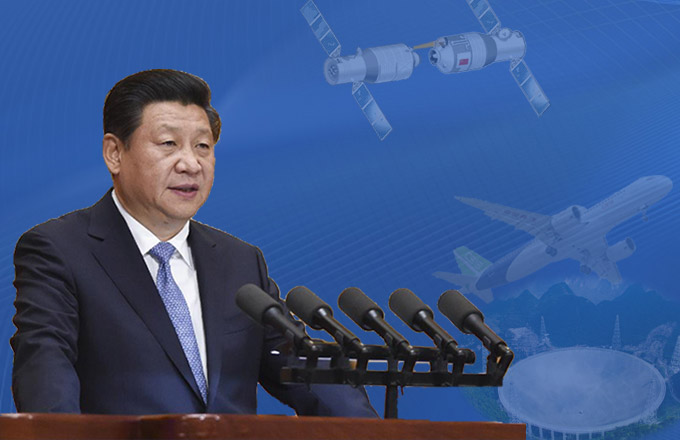

President Xi Jinping said in 2014 that fighting terrorism and religious extremism should be a top priority for Xinjiang, and boosting employment is seen by the authorities as key to regional security and stability.

The industrial center, which has clothing factories and weaving mills, has created more than 32,000 jobs, including 18,000 on production lines, according to Liu Yong, one of its directors. More than 95 percent of workers are from ethnic groups, and most are age 20to 35, he said.

"We're planning to set up more workshops in counties, towns and villages to provide more employment for people further out," Liu added.

Family business

The biggest employer on the Asku industrial park is Huafu Top Dyed Melange Yarn Co, which is headquartered in Shenzhen, Guangdong province. Over the past three years, it has hired more than 2,300 locals, and the number is expected to increase to 4,000 by the end of this year, said Li Jiansheng, its administrative manager.

The company has five workshops across Xinjiang - Aksu is the largest-and employs more than 5,000 workers in total, he said, adding that the number could reach 12,000 by 2020.

"We provide our workers with textile skills and security training," Li said. "Training for basic positions takes about 10 days, but it will take longer for more complicated roles."

For workers with no experience with textiles or cotton, or unable to speak Mandarin, the company arranges for them to study at its on-site school, where classes are taught by senior workers fluent in Mandarin and Uygur.

All expenses, including meals and accommodation, are covered by the company during the training period.

Adila Amut, 18, started working at the Aksu yarn factory seven months ago, after almost a year of being taught how to spin rough and heavy cord into the fine thread used by sewing machines.

She said she got the job to help her family. "I earn about 2,000 yuan ($290) a month, which covers my younger brother's school fees," she said. "My parents don't have much land, so they can't earn much from farming."

Her colleague, Padam Yassen, 43, is also using her salary to pay for school for her two younger sisters. Her higher income has meant her family can afford to leave the countryside and move into an apartment in Aksu.