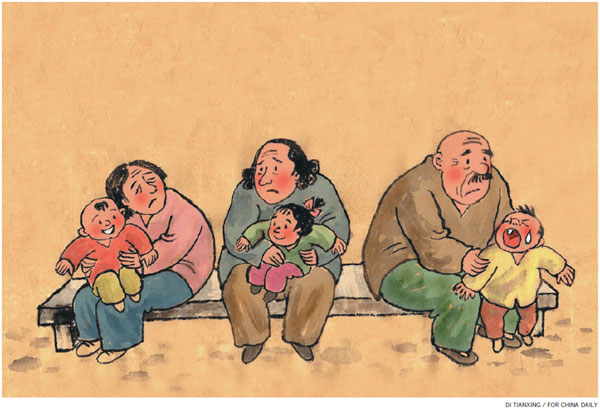

'Senior drifters' find big city life a lonely challenge

|

Many seniors who have moved to large cities to live with their adult children say they are losing touch with old friends at home and being treated as unpaid babysitters or housekeepers.Xinhua |

Many older people who live with their children in unfamiliar places miss their hometowns and friends, as Wang Keju reports.

A growing number of elderly people are moving to China's larger cities to be with their married children and help look after grandchildren, but rather than finding a source of solace, many of these seniors, far from friends and familiar surroundings, feel lost, abandoned and isolated.

At 1:10 pm one Wednesday, 61-year-old Chen Lizhen waited for a free shuttle bus to arrive and take her to a supermarket about 15 minutes away. It was the third time that week she had visited the store and her fifteenth trip that month.

Two hours later, with just a bag of apples and some cucumbers in a shopping cart, Chen was still strolling around the store, unaware of how many times she had circled the fruit and vegetable section. With still an hour to go before it would be time for her grandson to leave kindergarten, she decided to stick around for a while longer.

At one time, she wasn't part of the furniture at a supermarket. Instead Chen, a huge fan of Huangmei Opera, was an amateur but active performer with a group of theatergoers. She was nicknamed "Little Ma Lan", after a famous female Huangmei Opera artist in her neighborhood in Huaining, a county in the eastern province of Anhui.

She hasn't sung for four years. Since coming to Beijing in 2013 when her daughter-in-law gave birth to a baby boy, Chen has become a 24-hour housekeeper, babysitting her grandson and taking care of her son and his family.

It's not a rewarding existence. "The idea of sneaking back to Huaining has occurred to me many times," she said.

Senior "migrants" such as Chen in cities such as Beijing and Shanghai can easily be spotted in their residential communities, at school gates or in supermarkets.

They left their hometowns to live with their grown-up children who work in the cities. Instead, in many cases, they simply have become childminders for the family's third generation, and even though they come from different parts of the country and speak different dialects, they share the same name: "senior drifters".

Floating population

According to The Development of the Migrant Population, a report published by the National Health and Family Planning Commission last year, people aged 60 and older account for 7.2 percent of China's floating population of 247 million. That's about 18 million people, roughly twice the population of New York, and about 68 percent of these elderly migrants relocated voluntarily to live with their children or care for grandchildren.

Last year, there were 222 million people age 60 and older in China, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

"The phenomenon of 'senior drifters' is closely related to the ever-growing number of migrants and ongoing urbanization. Just as young migrants struggle to get by in cities, seniors who move to the metropolises will encounter even more trouble," said Zhou Xiaozheng, a sociology professor at Renmin University of China in Beijing.

In Chen's case that "trouble" is the dilemma in which she has been caught since her 3-year-old grandson began kindergarten last year.

Now suddenly without company, she has no way of killing time. With few friends to chat with, let alone to sing Huangmei Opera, she is swamped by memories of the old days back home, combined with loneliness and depression.

"People back in Huaining envy me for living in Beijing, but I'm jealous that they can stay at home with old friends and relatives," she said.