There were dust and fallen leaves everywhere. I wanted this place to become the cleanest place on earth, free from any grain of dust from the opposite side of the world. I took a broom to sweep it clean. Inside the grave house were urns row standing in a row some, were placed on a different level. Cousin showed me which one of the urns belonged to our grandparents. I imagined them looking at me. In one of those urns were the remains of the persons whose photos hung on the wall when Dad lived with us, those photos Dad brought all the way from China. These were people who knew we existed and thought about us and wondered how we look like and how we were doing; relatives that, before, weren't real to me; but now is.

A man was hired to transfer Dad's remains to a brown earthenware vase. With a crowbar he opened the wooden box with Dad's remains, the box I brought with me inside the belly of a plane named the City of Dubai. Free at last. Free at last, I thought, free at last.

|

|

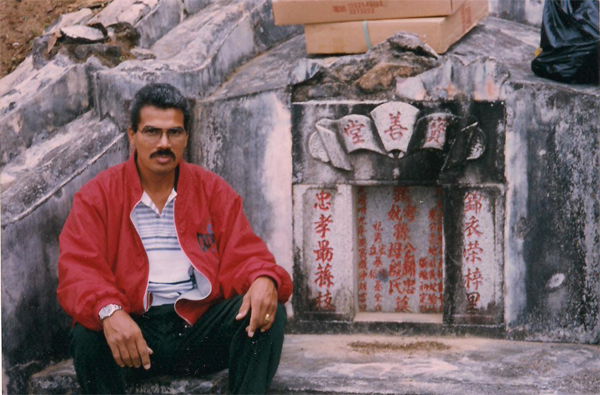

The author at his great grandfather's grave in China. [Photo provided to chinadaily.com.cn] |

"You wish to see?" They asked

I didn't. I didn't want to see what had become of my father. I didn't want to see a heap of bones. I didn't want to see what had become of the Chinese father who brought me Chinese food in a take-away container in a kindergarten at the opposite side of the world.

Carefully, piece by piece he transferred the fragile remains of my father to a burial urn. A piece of bone scratched against the inside of the jar sending cold shivers running down my spine. From inside the casket he took a pair of black socks, the socks Dad had on when he was buried thirty-two years ago. Inside these socks, was what has been left of his feet, small pieces of bones. He'd been waiting for one of his seven foreign-born children to bring him home. He sure wanted to come home, someone said. They nodded. Everybody nodded because they understood.

The old man took the socks with the bones in it and put them in the earthenware vase. The marble plate with the inscription of his name, date of birth and date of departure from the worldly life I put near his urn, a sign that he had lived and died in the West, a sign that he lived more in the West than in China. Nothing on the marble plate was correct, except the date of his passing away. Maybe someday one of his foreign-born descendants would return here, but I doubt that.

I read somewhere that according to the Chinese; a person who had been buried without a proper ceremony would haunt his relatives on the seventh night of the seventh moon when the gates of the underworld opened to let him out to settle his account with the relatives who didn't provide him with a proper burial. He'll haunt them and bring bad luck upon them. It took Dad thirty-two years to get a proper burial and three quarters of a century to return home.

After we prayed to the ancestors and offered them their gifts, we lit loud-banging firecrackers to scare away evil spirits. I was happy that I could bring him home but he cannot blame us because we didn't grow up with his traditions.

I said goodbye to Dad and the other ancestors wondering if I'll ever come back here.

I asked my relatives what they did with the roasted suckling pig. "Oh, we gave it to the workers to eat," they said.

The following day we went to Mount Dinghu, a retreat covered with dense forests, cascading waterfalls, low laying clouds that changes colors during the seasons, a place where people came to let off steam and philosophize about what's right or wrong with our world. The air was clean making breathing enjoyable, a tremendous place to exercise.

We strolled down serpentine paths winding up and down the hills. According to tests taken by the world heritage foundation the biosphere of this park contains more ions than any other place in the world. During the Tang Dynasty, 1200 years ago, Buddhist monks built magnificent temples on this site. They gave them such poetical names such as; White Cloud Temple, Double Rainbow Bridge, Heavenly Lake and so on. At Double Rainbow Bridge, one could see the reflections of the colors of the rainbow.

Along our path we encountered thousand-years-old inscriptions carved in rocks. After some time, we arrived at a place where young girls, dressed in fancy costumes, were busy dancing around the massive trunk of an odd-looking tree. From a distance, the branches of the tree looked like two giant arms stretching out the opposite direction, like a giant 'Y.' From a distance this majestic creation of Mother Nature looked like any normal tree, until one came near and noticed that it, in fact, were two trees of two different species, one grafted onto the trunk of the other, harmoniously existing in symbiosis with each other. I stood there admiring this peculiar creation of Mother Nature, not having a thought about the lesson I was going to receive.

Some young girls, hop-skipping were dancing and singing happily around the enormous trunk of the tree while spinning red threads around its massive trunk.

"What are they doing," I asked.

"Oh, a ceremony asking the tree deity to find them a suitable husband for an everlasting matrimony," my niece said.

"What are they singing?" I asked.

"An old song, it goes like this," And she started to sing, "If trees dies vines will stay with them forever. And if vines die, trees will refuse to abandon them, unless they too die." I understood that it was about the relation between husband and wife; it was about loyalty within the family. I thought about us children of mix race, East and West, children of parents with diametrically opposed concepts what a family was all about. Now I understood how deep the bond within the Chinese family went. No wonder Dad's family wanted to send a relative all the way to the Caribbean to take care of him when he became sick.

The red treads the young girls were busy winding around the tree represented the bond of trust that united the two opposites, man and woman, Yin and Yang. The tree, immovable with its roots firm into the soil reaching skywards; the vine immovable too, but able to climb in all direction but still tied to the soil both depending and nourishing each other.

"This is an indigenous Chinese tree on which a foreign tree was grafted about a hundred or so year ago," my niece said, reading from a board attached to the trunk. Mother Nature had inseparably united two species of two different continents. They had nurtured each other, lived from each other, and withstood the ravages of time together. Human hands have brought them together and forced them together, but nature made them inseparable. This unique creation of nature stood proud with a Y shaped trunk and a combined crown of two different species carrying a message that most people understood, but didn't heed. My niece turned around and looked at me then burst into laughter, "This tree is just like you, half Chinese half foreign," she said. Her remark struck me like a rock in the face. And I too had to laugh. She'd seen it right. This was the insight she got from observing this tree. I must admit, it was a clever observation a fitting assertion. I really was like this tree, half-Chinese half-Caribbean bound together in one body until I die, indivisible and inseparable. I was like a branch of a Chinese tree -perhaps a litchi tree - grafted on the trunk of a prickle tree or a cacti; incompatible with each other, but bound together by nature until the end. Did I come here, all that way, to this beautiful natural park to realize who I am and be aware of how difficult it was to be a child of two opposite cultures?

After leaving the sites with the beautiful names we traveled to a place called Zhaoqing, Zhaoqing meaning, "Bring happiness and luck" - a city on the bank of the Pearl River. From the window of the hotel room, I saw a landscape of rocky hill peaks, so called crags, protruding from the quiet surface of a lake. On a square nearby people were doing Tai Chi. From afar, they looked like dolls moving in slow motion. After a breakfast of watery rice gruel, pickled meat, and cabbage - we continued our sightseeing tour.

The author was born in 1947 in the Caribbean. He is the son of a Chinese immigrant and a Caribbean woman. Most of his life he has lived in Sweden where he studied and worked as a teacher and as an interpreter. He speaks, English, Swedish, Spanish, Dutch and some French but regrets very much that his father hasn't taught him his language.

[Please click here to read more My China stories. You are welcome to share your China stories with China Daily website readers. The authors will be paid 200 yuan ($30). Please send your story to mychinastory@chinadaily.com.cn.]