Fictional truth to power

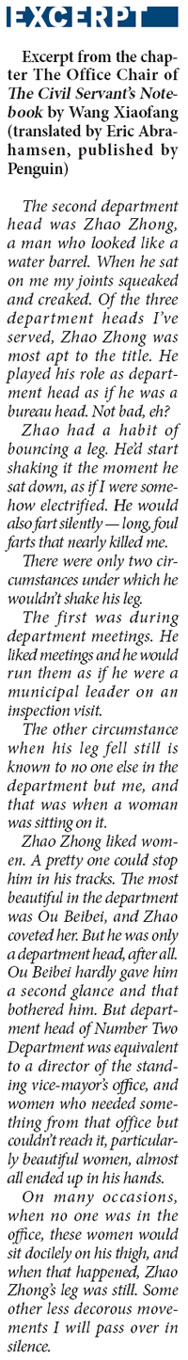

The novel's narration comes from not only people but also inanimate objects and places - office desks, cars, rivers and city squares, which offer their observations.

"This is very effective, as these are then able to explain events and incidents that happened in private, with no other person seeing them," Lusby says. "Wang is extremely experimental in his style."

His translator, Paper Republic founder Eric Abrahamsen, spent almost a year rendering the novel into English. "Definitely, you have to think hard about how to use different voices for the different characters," Abrahamsen says.

The book delves into scandalous and disgraceful rivalries for political prestige and details the distorted psyches of individuals caught up in the absurdity.

"The respect and pursuit of political status is ingrained in the core of many Chinese minds," Wang says.

"I write to expose and lash out against the harm it causes. I won't ignore any dimension of the dark side I've witnessed."

Abrahamsen believes the story is interesting in the way it reveals how the government works and that there's a natural audience curious to learn more about this.

"But the real appeal of the story is its human element - loyalty, betrayal, honesty and dishonesty - and how much human drama exists in the simplest governmental function," he says.

Wang says he saw too much as a civil servant and refused to participate in politics' dark side.

He gave up his political future to devote himself to writing.

Wang was born in 1963 to a father who was also a writer.

He joined the Shenyang municipal government after graduating with a master's degree in biology. His writing ability won praise, and he was promoted as the deputy mayor's secretary in 1997.

In 1999, his boss, deputy mayor Ma Xiangdong, was investigated for corruption and embezzlement. The courts found Ma had taken more than 9.76 million yuan ($1.57 million) worth of bribes and pocketed $120,000 of public funds, and Ma could not explain the origin of another 10.68 million yuan.

The notorious case, involving more than 120 high-ranking officials, attracted a huge amount of publicity.

Wang's political career was halted. He then tried his hand at business but failed.

In 2001, he happened to see the photo of Ma before the disgraced politician's execution.

"Ma's hollow eyes stirred my innermost urge to present my soul and examine it," Wang says.

He then wrote the first 10,000 words of what became the opening of his first novel, The Mayor's Secretary.

Wang has since produced 13 books to "build a spiritual homeland for the true, the good and the beautiful", he says.

The Beijing Office Director series sold two million copies.

Despite his success, Wang lives a simple and routine life, centered on writing and thinking.

"Lots of ideas come to my mind," he says. "I just can't stop my brain from racing."

He leaves a pen and notebook by his bed to record any inspirations that come from his dreams.

But Wang feels like time is running out for him.

"He's writing with his life," his wife says.

Zhang says he worked to the point of losing consciousness four times.

Wang's literary prowess is rooted in his reading, especially after Ma's case, he says.

He's familiar with writers like Marcel Proust, Vladimir Nabokov and Syrian poet Adonis, and has established a strategy to pursue reading that will benefit his writing.

After evolving from a civil servant to a full-time writer, Wang says he has no other way but writing to support himself.

"I simply can't stop writing."

Contact the writer at meijia@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

|

|