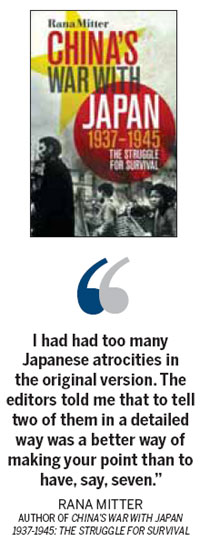

History and forgetting

"I was also able to draw on the fantastic scholarship on the Chinese mainland, Taiwan and Japan over the past 20 years," he says.

Mitter, 43, who is director- designate of the new Oxford University China Centre as well as a well-known BBC radio arts presenter, says it was a "multinational collaborative effort".

"I had a team of about eight or nine post-doctoral fellows and graduate students at Oxford who used to meet almost weekly to discuss different aspects of World War II."

This is also not some weighty tome but a very readable history with numerous gripping first-hand accounts that comes in at only 385 pages, partly on the insistence of the US publisher Houghton, Mifflin Harcourt which published it under another title - Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937-45.

"I wanted it to be manageable. Books of more than 500 pages tend to be respected rather than read. I wanted it to read as a story with characters," he says.

With any history of this conflict, one wants to know how it treats the Massacre of Nanjing, where women were raped and many innocent Chinese civilians gruesomely slaughtered in what many see as a uniquely evil incident.

Mitter, who deals with it in a single chapter, makes clear it was a tragic episode. "In the crucible of total war soldiers behave very badly ... Nanjing needs to be seen in its own terms."

"I don't think it is useful to have a ladder of comparative atrocity."

Mitter, a fluent Chinese speaker, says a risk for historians is getting diverted by the blood and gore of this conflict.

"I had had too many Japanese atrocities in the original version. The editors told me that to tell two of them in a detailed way was a better way of making your point than to have, say, seven," he says.

The book sets the war in historical context and how before the Japanese invasion of Northeast China in 1931, Japan was seen as a beacon of development in Asia and a place where a number of China's eventual war leaders, including Chiang himself, had studied.

"Japan can be seen as a monster and invader but had actually been a mentor for China. Unlike China, Japan had modernized and learnt fast that it needed to have a strong and developed economy," he says.

Although Japan was a more advanced country, it would be wrong to conclude the Chinese army was second-rate. Some 30,000 of its officers had been trained by the German generals Hans von Seekt and Alexander von Falkenhausen, and the resistance they provided helped deny Japan victory.

"There was a certain group of Chinese troops that were very well trained and this has been a discovery over the past 10 to 15 years by both Chinese and Western historians."

The game plan for China was to avoid defeat until it got international help, which came in the not-so-harmonious form of the Americans led by General "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell after Pearl Harbor.

"There is a very close link between the toxic relationship that grew up between China and America and the failure to understand each other in the war years," he says.

Mitter says the war clearly still has legacies - China's permanent membership in the United Nations Security Council for one, and also in Sino-Japanese relations.

"There is something in the (Chinese) public culture that argues Japan has not properly atoned for the war and it remains a running sore, particularly in sensitive places like Chongqing and Nanjing. I think both sides still need to understand more about the history," he says.