The ancient army that's still growing

By Zhao Xu and Lu Hongyan ( China Daily ) Updated: 2014-10-22 07:48:30

|

|

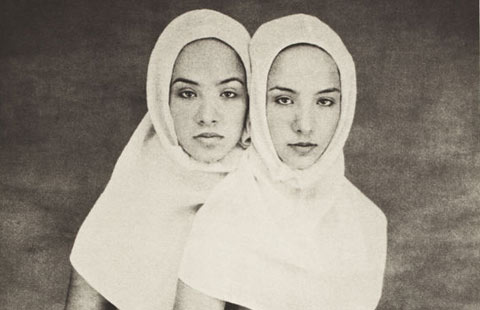

A model at the exhibition shows how a warrior may have looked when the figures were made 2,000 years ago. [Photo/China Daily] |

History unearthed

Yang Zhifa, a local farm worker who, by pure chance, allowed the first rays of light to strike the underground army for millennia, would agree with Ma's assertion.

As he and two other villagers were digging a well on a chilly spring day 40 years ago, the then 36-year-old Yang's spade bounced off the head of a buried warrior. Today, the hoe he wielded on that fateful day is framed and hanging proudly on the wall of his sitting room.

The army was assembled for Ying Zheng, also known as Qin Shi Huang, or "The First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty". Upon ascending the throne at the age of 13, the boy emperor immediately embarked on a seemingly unstoppable quest for greatness - both in this world and the next.

By the time he died, in around 210 BC at the age of 50, he had united China, and standardized the national writing system, as well as the units of currency and measurement. He was also responsible for the construction of some of the first sections of the Great Wall, and a fabled sunken mausoleum, buried under a huge mound of earth, whose ground plan is believed to have been an accurate depiction of China and included rivers of flowing mercury. Understandably, the emperor deployed a formidable underground army to safeguard his magnificent tomb.

The warriors were the final piece of a jigsaw. More than 700,000 laborers worked for 38 years to complete the task, and - somehow appropriately - its end sounded the death knell of an empire many thought undefeatable. The Qin Dynasty collapsed a mere four years after Ying Zheng's death.

'The end of the beginning'

"If the completion of the Terracotta Army - although, some say it was never completed - can be seen as the beginning of the end for the empire, then its discovery was indeed the end of the beginning for us," said Xia Yin, a conservationist from the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum Museum.

"What our ancestors spent three decades building will take us forever to decipher."

In Pit 1, the largest of the four pits that house the terracotta troops, soldiers are lined up in battle formation across an area the size of two football fields. The soldiers stand on well-baked pottery bricks sturdy enough to sustain the figures, which weigh an average 200 kilos each. A wooden ceiling that once sheltered the warriors rotted away hundreds of years ago, along with the large beams that supported it and the rammed earth that was laid on top.

"All the wooden sections have been reduced to dust by the grind of time, but sometimes, absence is felt more acutely than presence," said Pan Ying, a 28-year-old museum guide, pointing to impressions left in the earth by the wheels of long-gone wooden chariots, and the undulating earth that avalanched into the pit when the rafters gave way, completely covering many of the terracotta figures.

The museum has restored and displayed about 1,200 of the estimated 6,000 warriors in Pit 1. But the mystery surrounding the army has been deepened, not lessened, by the artifacts that have been unveiled, according to Pan.

"Artistry is by no means compromised by scale. If you zoom in on the individual soldiers, you'll see each one has distinct facial features and expressions," Pan said.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Raymond Zhou:

Raymond Zhou: Pauline D Loh:

Pauline D Loh: Hot Pot

Hot Pot Eco China

Eco China China Dream

China Dream China Face

China Face