Birds of a feather

|

|

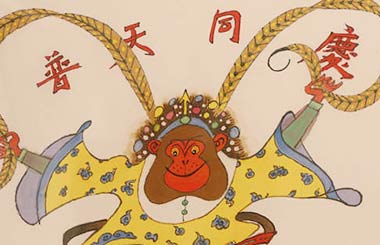

2017 is the Year of the Rooster, according to the Chinese zodiac. PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY |

2017's zodiac animal is a domestic fowl that we consume without giving it much thought. But it could be a minefield for cultural misunderstandings once you go beyond simply nibbling chicken feet, writes Raymond Zhou

Of all 12 zodiac animals, the rooster may have a cleaner image than the pig, but it does not even rank as high as the pig on the list of foods' prestige. In the food chain of exclusiveness, chicken has gone downhill in China over the past three or more decades. When I was a kid, chicken was a luxury item, affordable to most families only for special occasions like New Year's Eve.

Imagine my shock when I first arrived in the US and saw the most economically deprived gorging themselves on fried chicken. Back in China, the ubiquity of KFC and local fast-food outlets has not pushed it down to the bottom of the ladder, at least not yet. It is still very much a middle-class entree.

Before the arrival of industrialized chicken farms, chickens were raised by rural households who used leftover food as the main source of fodder. Hens were for laying eggs, which could be sold for pocket change or consumed. Roosters were to be food, with their feathers made into fans or dusters. Chicks could be pets, but they quickly outgrew that phase. Kids or adults rarely developed the kind of attachment to a chick they would to a cat or dog.

Chicken feathers are also used for shuttlecocks in a game known to the Tujia ethnic minority as "kicking a chicken". Players kick the shuttlecock high, as if serving a volleyball, and whoever it lands near has the right to strike at anyone - with straws, not the shuttlecock. Mind you, they do not hit someone they hate, but rather someone who is a secret object of amorous feelings. Hence, it is a dating game.

Backyard chicken coops still exist, though maybe not as extensively due to the rate of urbanization. But the old economics of raising chicken no longer apply as it often makes more sense to buy processed chicken from the supermarket. This has spawned the rise of organic, free-range chicken, called tuji in Chinese. They are able to roam free and scout for their own food, rather than be fed processed feed. They are supposed to be more tasty.

Tuji are like the rural leftover children who are not submitted to the rigorous regimen of parental monitoring or heavy curriculum. Their guardians tend to be more laissez faire, too busy struggling to make ends meet to mollycoddle them as pets. As chickens, they are more valuable than their factory-farmed counterparts, but the "free-range" human beings of the countryside are not valued for their wild lifestyles, bruised skin, tattered clothing and all. It is a paradox that inspired me to write a short allegorical story years ago: What if humans become food for some kind of giant monster? Will they prefer the rural kids among us over our polished urban brethren?