Birds of a feather

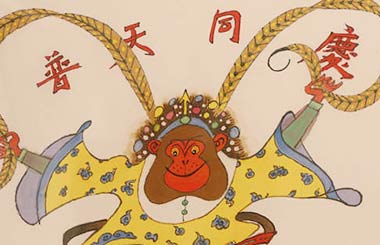

Whenever I look at an artist's rendition of roosters on the Lunar New Year poster, with its comb in full bloom like a blossoming chrysanthemum, I am drawn to the paradox of the symbol. It's supposed to bring us good fortune, yet we do not squirm when serving it as food. Many catchphrases from bygone eras portray the fowl as a target for killing, usually for food. "To kill a chicken to scare a monkey" is a warning; "to kill a chicken with a knife meant for cattle" is overkill; "a hand unable to bind a chicken" is weakness; "to kill the hen for the eggs" is, well, the exact meaning of the Aesop fable, except that another fowl, the goose, has taken its place.

Though much larger in physique than the cricket, the chicken is often used in Chinese colloquialisms as things small or small-minded. "A crane standing in a group of chickens" is naturally tall and conspicuous by comparison; "feathers of a chicken and peels of garlic" denote insubstantial stuff; "a small abdomen with chicken intestines" suggests a person who is narrow-minded.

The domesticated bird is also featured prominently in descriptions of chaos. Phrases like "chickens and dogs not being peaceful", or "chickens fly and eggs crash", or "chickens fly and dogs jump" illustrate a commotion. On the contrary, chickens and dogs can also create a idyllic picture of harmony, depicted by Laozi, China's ancient philosopher, as "chickens' crows and dogs' barks being heard among neighbors".

Make them fight or make us fight?

Cocks not only utter the shrill squawking sound that may punctuate or accentuate a scene of rustic tranquility, they also engage in melees for various reasons.

Cockfighting was never as popular in China (with the exception of some ethnic minorities) as, say, cricket fighting, which was an aristocratic pastime that permeated the country during the Qing Dynasty (1636-1912AD). However, the blood sport can be traced back to the pre-Qin era (BC2100-BC221) in China. It prevailed during the Tang Dynasty (618-907AD), especially among the ruling class, and was later promoted in the military to boost morale, spreading to neighboring countries like Japan.

Roosters carry a reputation for having a short fuse and being hot-tempered. Whenever they duke it out, they create quite a spectacle, albeit a bit on the quick side. When I was young, adults would break up such scuffles lest a rooster die before the year-end feast. Never in my memory did anyone point to me and say: "Hey kid, do you want to observe how animals establish dominance and win over the fair sex?"

Chinese people think the rooster's fighting spirit is in its blood. In ancient times, people used the liquid for swearing ceremonies, such as the forming of a brotherhood. I surmise they were supposed to use their own blood, but chickened out (Pun intended.) Today, drinking chicken blood is believed to enhance bravado. Most would boil it first, so it's served like a brownish beancurd. But some prefer it uncooked, supposedly to preserve its essence. In the late days of the cultural revolution (1966-76), a pseudo-scientific trend swept the nation, making many believe that injecting chicken blood into a human body would increase vitality. Though the practice is now gone, the term has stayed with us, meaning hyperkinetic: If an industry grows in double digits, Chinese could describe it as "injected with chicken blood".