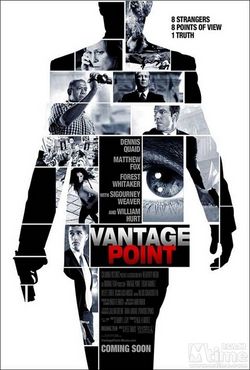

Directed by Pete Travis, starring William Hurt, Sigourney Weaver, Dennis Quaid, Forest Whitaker, Eduardo Noriega

Expertly directed by British moviemaker Pete Travis, the movie is the first filmed screenplay of American Barry L Levy. The work that comes most readily to mind is Kurosawa's complex Rashomon, in which a violent incident in medieval Japan is witnessed by five people, most of them lying. But the most significant exercise in this area is Robert Browning's novel-length poem The Ring and the Book, telling the story of a murder in 17th-century Rome from numerous points of view. The "ring" of the title refers to the artistry that transmutes "pure crude fact" into a vital, organic whole, while "the book" is the random assemblage of facts and opinions contained in a contemporary documentary record of the crime that Browning came across.

Vantage Point is not exactly Browning (neither Robert nor Tod), but it grabbed viewers by the lapels throughout while packing an astonishing amount into its 90 minutes. Unlike Rashomon (as well as the contested evidence of 22 November 1963 in Dallas's Dealey Plaza and 31 August 1997 at the Pont d'Alma tunnel in Paris), everything we see is fact as viewed and interpreted from different points of view. There are no visual lies, no examples of what Wayne Booth dubbed "the unreliable narrator", no false flashbacks of the sort Hitchcock pioneered in Stage Fright.

The first sequence is seen through the eyes of the TV outside-broadcast director played by Sigourney Weaver. She's sitting in a van with banks of screens around her, issuing orders to her camera crews, deciding what viewers will see of the world, trying to orchestrate life. The first thing she notices is that President Ashton (William Hurt) is accompanied by a secret service agent (Dennis Quaid), who a year before had taken a bullet while on presidential protection duty.

After the assassination, there's a small explosion some blocks away and then a horrendous one that creates havoc in the plaza. The winding back of film becomes a metaphor of memory, of retracing time, and each extended sequence begins at noon, as witnessed from the vantage points of the Spanish police, various Islamic terrorists operating out of Morocco, the president's inner circle of advisers and, most significantly, an American tourist (Forest Whitaker), who's recording the events on his camcorder. Like the obsessive surveillance expert in Coppola's The Conversation, constantly replaying his tapes to reconstruct the eponymous dialogue, we are led to discover new things and reinterpret what we have been shown earlier as fresh light is cast on what we've seen and new terms added to the elaborate equation. A man and a woman seen chatting - are they lovers or conspirators? Casual conversations become sinister encounters. A foolproof security system is exposed as inadequate in the face of a brilliantly mounted conspiracy. Our doubts and certainties are variously confirmed and confuted by some clever plotting that draws on sources as various as The Prisoner of Zenda and Richard Fleischer's The Narrow Margin.

The chases go on a little too long and as there have been nopit stops for humor, audiences might well laugh at quite reasonable lines that serve to wrap up the plot, especially as they come after one of the terrorists says: "We need to tie up all the loose ends."

The Guardian

Book