|

|

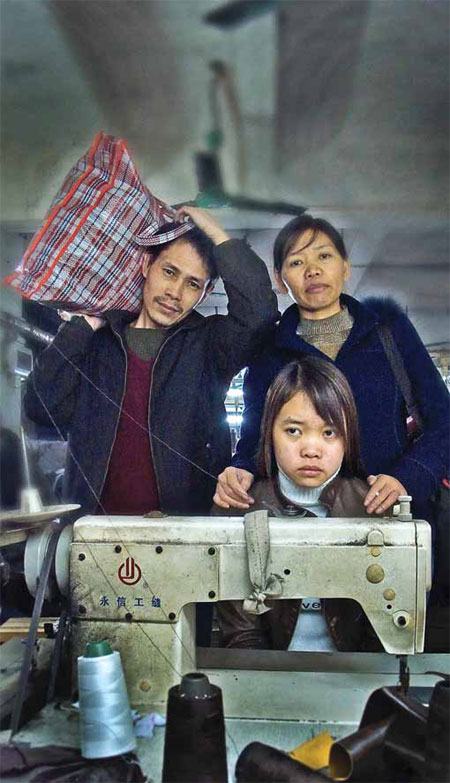

A scene from Fan's doecumentary, Last Train Home. Photos Provided to China Daily |

|

|

Fan has focused his lens on migrant workers. |

|

|

|

Documentary director Fan Lixin has launched a personal screening odyssey to promote his film on migrant workers. Zou Hong / China Daily |

Documentary maker Fan Lixin has had an unexpected big-screen hit with his first work, Last Train Home, about the annual exodus of migrant workers from their urban workplaces to their rural hometowns during Spring Festival.

The visually amazing and emotionally engaging work, filmed in 2006, took three years to complete and has garnered more than 60 prizes, including Best Feature-Length Documentary award at the 22nd International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam in 2009.

But its migration to the cinema screen has surprised a lot of people and is due to Fan's "one city, one screening" concept.

Fan says he spent two years showing his documentary at film festivals around the world before returning to China in 2011 and ensuring his film was seen around the country.

"Chinese films face stiff competition from Hollywood, though some have done well," Fan says. "But documentary movies aren't normally so lucrative."

He adds that even though he received a grant of 60,000 yuan ($9,456) from the Sundance Institute Documentary Fund, which encouraged him to release the work in China, he could not afford the "way more expensive fee" charged by a distribution company for a cinematic release.

It was Wu Jing, a programming manager at MOMA Broadway Cinematheque, an art house cinema in Beijing, who inspired Fan.

Wu suggested premiering the film in China MOMA in July 2011 and showing it once a week for five months. "Since we didn't have enough money to publicize the film, we had to let the reputation build slowly," Wu says.

Full houses convinced Fan the format could be replicated in other cities. Hence, the "one city, one screening" idea, for which a cinema would screen the documentary in a city for at least a month.

Fan says cinemas like Beijing's MOMA Broadway Cinematheque were preferred. But if cities did not have such a resource, then theaters near universities were chosen, as they were likely to attract a more art-house crowd.

Although Fan didn't have enough resources and connections to locate and negotiate with suitable cinema owners, luck was on his side, as one of his friends was part of an online independent film group.

"My friend was well-connected with independent film lovers who are familiar with the cinemas of their respective cities," Fan says.

They helped Fan find the cinemas. Another friend helped him sign contracts to arrange screenings.

"Thanks to their assistance, nine cities, including Wuhan, Guangzhou and Chengdu, were pinned down within two weeks. That's a miracle," Fan says.

The first-time director then embarked on his personal screening odyssey and visited nine cities within 10 days.

His routine was to rise at 5 am, arrive at the airport at 6 am, get to the city between 8-9 am, and take interviews for three hours at the cinema.

"After a short lunch, the interviews continued and lasted for the whole afternoon," Fan says, adding he returned to his hotel about 10 pm to write up his conclusions before packing and getting to sleep at 12 pm.

To cut expenses, Fan stayed at budget hotels and lugged promotional materials, such as posters, himself.

The 35-year-old says he was disappointed when just 50 people showed up in Jinan, capital of Shandong province, on the tour's first leg.

But he soon accepted that this was a grassroots form of distribution, and it would take time to build interest.

So far, Last Train Home has shown in 19 cities, and Fan plans to continue his tour.

Professor Zhang Tongdao from Beijing Normal University's School of Art and Communication says Fan's promotional format is courageous.

"It needs to pass the test of time, but such an initiation is worthy of admiration," Zhang says.

Fan says his decision to shoot a documentary about migrant workers arose from his feelings of social injustice.

A former journalist and cameraman for CCTV, he often went to remote areas and was shocked by the difference between life for those who lived in rural areas and in the rich cities.

"The kids in rural areas lack parental care. Why? Because their fathers and mothers are mining and housekeeping and washing plates in big cities," Fan says.

"The migrant workers are exploited for urban modernization, but they still live in the cracks of society and lack respect."

He chose the Spring Festival migration because it was an ideal subject to trace the effects of long-term separation on migrant workers' families.

"The documentary was intended to establish a monument to the backbone of the country. Migrant workers deserve recognition."

When filming the documentary in Guangzhou in 2008, Fan was squashed by crowds scrambling to get on the train at Guangzhou railway station.

"It was snowing, and the people were jostling, crying and cursing. People stepped over those who had fallen, to move forward, and there was no dignity to the occasion at all," he says.

"All this happened because they wanted to return to their hometown and see their children and other family members."

Fan says he focused his lens on just a fraction of the tens of millions of migrant workers in China that regularly overwhelm the country's rail system.

"The documentary is so heavy that it would be a shame if our countrymen cannot see it in cinemas," he says. "That's why I spared no effort in pushing the film on the big screen."

Fan's latest project centers on the second generation of migrant workers and is currently in the casting stage.

Fan will also produce a documentary that records how rural teenagers become boxing champions.

"And then, I will begin the next round of my screening odyssey," he says.