|

|

Li Suzhi gives a health checkup to a Tibetan girl during his rounds among villages in Tibet. Photos by Zhang Zhen / for China Daily |

|

|

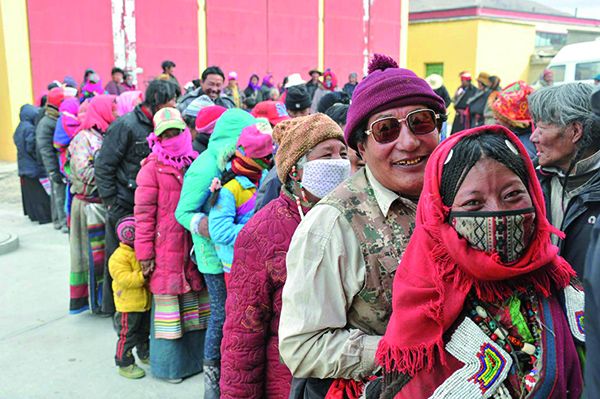

Patients wait in a long line to see doctor Li Suzhi, whom they believe has magical powers. |

For 36 years, Li Suzhi has overcome the odds and the altitude to give health and hope to Tibetans. Zhang Yue reports in Lhasa.

When surgeon Li Suzhi first arrived in Lhasa, capital of the Tibetan autonomous region, in 1976, he thought to himself that it was a place of life and death. "My first week here was filled with headaches, difficulty breathing and throwing up, just like anyone else who first visits the plateau," Li says. In the following 36 years, Li worked with all his might to rescue people from sickness and death. He is now head of the General Hospital of the Tibet Military Command of the PLA and has helped with important breakthroughs in treating various high-altitude sicknesses and developed methods for performing surgeries at higher altitudes than previously possible.

As well as providing treatment at the hospital, the doctor makes his rounds among villages, where former patients often honor him by bending down and presenting him with a hada, a piece of silk that denotes respect.

"I had no idea he was the head of the hospital when he first came to see me," says Gesang Zhuoga, a 42-year-old, who was eventually hospitalized for congenital heart disease. "He saved my life by operating on me. He told me not to worry, and I could return home to pick caterpillar fungus and make money."

The 58-year-old doctor knows very little of the Tibetan language. Instead, he smiles, puts his hands together and pats patients who come to express their gratitude.

Many ill Tibetans choose to go to a temple rather than a hospital and pray for recovery, when they feel ill, which is where Li often finds patients on his rounds.

During the recent Spring Festival, Li and his team visited nearly 20,000 villagers and performed 117 surgeries, sometimes in converted trailers.

Li's idea of working in Tibet came to mind when he first operated on a young soldier who was serving in the People's Liberation Army in Tibet in 1976.

The young man had been suffering from short bowel syndrome before he arrived in Shanghai for treatment.

Li could not understand what took the soldier so long to get treatment.

"The oxygen in Tibet is only 60 percent of what it is in Shanghai, so there are many surgeries that cannot be done in Tibet," the young man told him. "Many died on their way to receive surgery inland."

The young man shared his stories in Tibet with Li. It inspired him to help.

"I am a doctor, and I save lives," says Li, who volunteered to head to Tibet with some other doctors.

His first frustration came when an 18-year-old Tibetan girl named Zhuoma was sent to hospital in 1978 because of a sudden heart attack due to congenital heart disease.

Though Li and his team did all they could, the girl died a few days after she arrived at the hospital.

"I saw her stop breathing on the operating table," he recalls. "I've never felt that bad. It was a sense of guilt."

He learned that congenital heart disease is quite common on the plateau. For instance, of the 20,000 locals whom he recently gave health checks to, 60 suffer from the disease.

Surgery is the best way to treat the disease. Yet at that time, no surgery was done in places above 3,500 meters in China, or elsewhere.

"The choice for Tibetans was simple: Spend a lot of time and money to go to inland cities for surgery or wait in Tibet for limited treatment that might lead to an early death," he says.

After Zhuoma died, Li started working on methods to operate on congenital heart disease patients at high altitudes.

After more than 20 years of research and 200 experiments on dogs, Li's first surgery on a person was his relative, a 6-year-old girl, who suffered from the disease.

"If anything went wrong, the patient would have died," Li says.

When the operation was successful, Li burst into tears and everyone in the operating room cheered.

He conducted similar research on liver transplant surgery and successfully conducted the first liver transplant in China in 2005, on a 50-year-old Tibetan, also at an altitude of more than 3,500 meters.

"We think of doctor Li as a magic person. Many Tibetans respect him as a god," says Menba, Tibet's first liver transplant patient, who says he wanted to die before the operation because he was so sick.

Li says he is full of gratitude to the army. He was born and raised in a poor, rural family in Linyi, Shandong province, and "never had enough food to eat" during his childhood. This improved after he joined the army in 1970 and received a strong education.

Yet Li has complex feelings about his own family.

Li's wife, Guo Shuqin, used to be doctor at the same hospital. They met and fell in love soon after they both volunteered to work in Tibet in 1976 but then faced decades of separation.

In 1982, when Guo was seven months pregnant, the stress of living at high altitudes forced her to leave her husband and return to her hometown of Dalian, Liaoning province. Soon after, their daughter, Li Nan, was born.

The family has seldom been together since.

"I was working at the hospital in Tibet when my daughter was born," Li recalls. "Four days later, I stopped over in Dalian on a business trip and spent one day with her."

He admits he spoke to his daughter very little while she was growing up, and Li Nan admits telling classmates, "I don't have a father".

"She did not call me dad until she was 18," Li says.

This year has been a different story, as Li Nan has graduated with a physician's degree from Third Military Medical University and volunteered to work as a dentist at the same hospital as her father.

"The three of us will be together now," says Li, speaking of her parents and new job.

She joined her mom and dad for medical visits to villages in Tibet during the recent Spring Festival, the first time they have been together.

"It only took me a little while to understand my dad," she says. "You can't let go when you see people who do not know what to do with their sickness. This is what makes us doctors."

Contact the writer at zhangyue@chinadaily.com.cn.