Racing to breed species in zoos

FRONT ROYAL, Virginia - With extinctions rising and habitats being destroyed, zoos are trying to breed about 160 endangered species.

But 83 percent of those species in North American zoos are not meeting the targets set for maintaining their genetic diversity, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums reports.

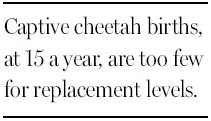

After two decades, the captive population of 281 cheetahs in North America gives birth to only 15 cubs, on average, a year, half of what is needed to maintain a healthy replacement level. And they are not nearly as difficult to breed as pandas, which last produced a cub in captivity in America in 2010.

Zoos must learn to mate animals as so-called insurance populations, before their situation in the wild becomes untenable, said Jack Grisham, who coordinates the association's cheetah breeding plan. The disappointing success rate has led many to say they would prefer to see the money go to preserving wild habitats and species.

"I'd be happier about captive breeding if I thought it helped wild cheetahs," said Luke Hunter, president of Panthera, a nonprofit group with offices in New York and London that works on global conservation efforts for big cats in the wild, including cheetahs. "Free of threats, they breed like rabbits in the wild. They don't need supercostly assisted reproduction - they need a place to roam."

Each year the Smithsonian's National Zoo in Washington spends about $350,000 on breeding cheetahs at its 1,300-hectare campus here in Front Royal, which houses 18 other species. Similar programs exist at four other centers run by zoos.

At the turn of the 20th century, roughly 100,000 cheetahs roamed from Africa to the Mediterranean to India, according to the Smithsonian. Today, experts estimate 7,000 to 10,000 remain in the wild as a result of habitat loss, poaching, and conflicts with farmers and ranchers.

Mr. Grisham said the pressures on animals in the wild are so great that zoo animals may someday have to serve as a genetic insurance bank.

In a closed population, as in zoos, the priority is high levels of genetic diversity to maintain a species' adaptability and prevent inbreeding. The result is a kind of reverse natural selection, with the animals with the lowest rate of success vaulting to the top of the priority list because of the rareness of their genes.

Many zoos do not have enough genetic variation to ensure long-term survival in captivity. "Noah got it all wrong," said Sarah Long, director of the Population Management Center in Chicago. "One or two or even a dozen of each species is not enough."

The association runs nearly 600 cooperative breeding programs, but so far has formal breeding plans for only 357 species. About 55 percent of those species with plans are considered imperiled in the wild by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, among them the western lowland gorilla and the scimitar-horned oryx.

Still, 40 percent of those 357 managed populations are dwindling. The number of Andean bears is shrinking because zoos scaled back breeding years ago and the population has become too old to reproduce. The Nile lechwe, an antelope, is believed to be suffering in captivity because zoos are allocating less space to rare hoofed species.

Researchers lack adequate knowledge on artificially inseminating many exotic animals, so for now, most zoo animals mate the old-fashioned way, which presents its own logistical puzzles.

An institution may be reluctant to give up a popular chimp or penguin. Animals available from overseas can be blocked by agricultural treaties, diplomatic problems or quarantines.

And animals, like humans, have their own ideas about their mates.

African penguins are generally monogamous. At the New England Aquarium in Boston, they are paired by keepers with an appropriate genetic match.

But some 25 percent of the time the penguins refuse the designated suitor.

Researchers are still trying to master the dynamics of cheetah mating, said Adrienne Crosier, director of the National Zoo's cheetah breeding program.

For decades, zoos housed and treated all big cats similarly. But their mating patterns can be radically different. For example, clouded leopards, a critically endangered species, pair up with their mates early in life. If they are introduced for mating as mature adults in captivity, it causes extreme stress, and the male will occasionally kill the female. Such attacks once occurred repeatedly.

Cheetahs, by contrast, do not pair off.

Researchers have learned that fertile female cheetahs that are unrelated or have not been raised together should not be kept together because the nondominant female will experience so much stress that she stops going into heat.

Zoos are now emphasizing conservation centers that are less like zoos and more like ranches or a safari park. The animal conservation center here has enough space to mimic the wild.

The five centers that breed cheetahs now account for a disproportionate number of the victories, including an unusual case here in 2010.

A 5-year-old female cheetah had remained barren through many breeding attempts over two years. So a new male, named Nick, was trucked in from Florida, 1,450 kilometers away.

Born as a lone cub, the cheetah was removed from his mother's care because of yet another discovery: the cheetah will not produce enough milk for its baby if there is only one suckling. Anticipating that possibility, Dr. Crosier had timed another cheetah pregnancy to coincide with that of Nick's mother.

When the next birth - another singleton - took place, staff members placed Nick alongside the new baby.

The mother could easily have killed him with a snap of her jaws. Instead she nursed both cubs. It was the sixth such transplant in American zoo history.

Nick was recently separated from his adoptive family, and Dr. Crosier hopes he will soon breed.

"He has great genes," she said proudly.

The New York Times