Farmers’ Comments on “the Farmer-workers Tide” --Questionnaires for 818 farmers seeking jobs out of their villages

Zhao Shukai

The survey was conducted in May 1999 with the focus on the attitude of farmers toward the society, especially toward the government policy. A lot of subjective indexes were used in the questionnaire, asking the respondents about their actual feelings. The questionnaire is composed of three parts: the general picture of farmers working away from their hometowns and the government management; the rural situation and the implementation of government policies; the grass-root organizations in the countryside and the image of village heads. This article, focusing on the trend of the “farmer-workers tide”, is the first part of a preliminary analysis on the questionnaire.

The respondents are of the lower or lower-middle strata of farmer-workers. Based on their observation of their hometowns and themselves, they evaluated the trend of the current farmer-workers tide and described how they felt while working away from their hometowns. The analysis shows that the farmers’ desire to work out of their villages remains strong, whereas the employment environment has deteriorated in the past two years or so and the farmer-workers’ worries have increased. A potential group of people among the farmer-workers with an obvious tendency of becoming vagrants merits attention.

I. Sampling method and features of samples

In order to guarantee that the respondents are familiar with both the countryside and the life of farmer-workers so that the talk is rich in content, it is designed in the questionnaire that all respondents must be over 20 years old (born before December 31, 1978), stayed for more than 2 months in their own villages in 1997 and 1998 respectively, and they must have worked away from their villages for more than 2 months respectively in the said two years.

The survey was conducted at Beijing Railway Station and Beijing Railway West Station, where farmer-workers often stay briefly. Since they tended to gather at the square either to sit on the ground or stand in groups, we chose samples from groups. If the group was bigger than ten persons, we chose two from it. If the group was less than ten, we chose one. Although the sampling was not probability proportional, it was to some extent random. Fifteen university students spent six days (three days for each of the station) to interview 873 farmer-workers and gathered 818 effective questionnaires. Due to the random nature of the sampling, the conclusion of the data analysis is only applicable to the sample groups.

The native places of the samples are distributed in 779 villages, 436 townships, and 434 counties of 22 provinces. 174 people, or 21% of the respondents, are from Henan Province, who constitute the largest group. People from Sichuan Province come to the second, accounting for 17%. The third group is people from Anhui Province, making up 14%. The rest come mainly from Jiangsu, Shandong, Hubei, Hebei, Shaanxi, Chongqing, Jiangxi, Liaoning and Hunan.

The features of the respondents. 89% of the respondents are male, and only 11% are female. 92% of them are under 45 years old. Those under 35 make up 72% of the total respondents. 75% of them are married, out of which 85% live separately from their parents. As for their educational level, 87% graduated from junior middle school or below, 10.8% from senior middle school, and the rest have college degrees or above. Comparing with the previous samples of farmer-workers, the present groups are older and with obviously a higher proportion of married people and more social experience.

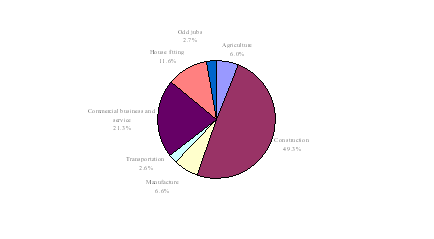

The employment sections of the respondents (see Figure 1). 49.3% of them are in the construction section, 21.3% in commercial business and service, 11.6% in house fitting, and the rest in sections of manufacture, agriculture or transportation. As for the status of employment, 56% of them are employed, 24% are jobless for the time being, 10% are self-employed businessmen and 9.5% are odd jobbers. The sectoral structure is closely related to the sampling method, as the respondents were chose according to their clothes.

Figure 1 Sectoral Structure of the Respondents

|

The majority of the respondents are ordinary villagers. 42 of them are Party members, which makes up 5% of the total. 57, or 7%, used to be village heads, out of which 24 used to be team leaders of their villages, 10 were once members of either the village committees or the village branches of the Party Committee, 7 used to be directors of village committees, 3 were secretaries of the village branches of the Party Committee, and the rest 13 were either village accountants, militia leaders, secretaries of the Youth League Committee or heads of other units in their villages. The current jobs of these former village heads show no difference from the sectoral structure of the total samples. 83 of them, about 10%, have lineal relatives who are main heads of their villages (party secretary or director of the village committee), out of which 54 are children of these heads, 28 are brothers of the heads and only one girl is a head’s sister.

95% of the respondents have contracted land at home and 5% have not. Out of those who have contracted land, 90% leave the land to their families at home to be cultivated, 8.6% re-contracted the land to others. Few leave the land deserted.

In general, they are a group of rural population who still have close connection with agriculture. They are the farmer-workers in the normal sense. Doing the hardest labour work, they belong to the middle or lower middle strata of farmers who work away from their hometowns.

II. Changes in how farmers organize themselves to work away from their hometowns in the past two years

This is a group of farmers who have fairly long-term experience of working out of the villages. Those who started to work away from the hometowns before 1990 account for about 30% of the respondents. 40.6% of them started between 1990 and 1995, 9% in 1996, 11.6%, or 95 people, in 1997 and 6.6%, 54 people, in 1998. The rest 20 people couldn’t remember when they first left home to work.

When answering the first question – “How did you find your first job?”, 628 respondents said with the help of their relatives or people from the same village they found their jobs. These people account for 76.8% of the total. 144 people, or 17.6%, found jobs by themselves. 38 people, or 4.6%, got jobs through job agencies or job fairs. 7 people, or 0.9%, found jobs through advertisement. And there is one who went back home because he couldn’t find a job. The above result proves again that the majority of the farmer-workers are not “aimless migrants”. They left home to follow certain aims.

Question – “How did you find the current job?” 612 people, or 75% of the 818 respondents are employed. 50% of them, or 412 people, got jobs through recommendations of their relatives or people from the same village. 18%, or 149 people, found jobs by themselves and 24 through job agencies or job fairs. 7 found jobs from advertisement. And 18 are self-employed businessmen. This is of the same order as that of their first job seeking experience. However the proportion of the first mode of finding jobs dropped nearly 17%. That is to say the importance of family or geographic relationship in finding jobs is reducing, which means more farmer-workers need to widen their social channels in employment. There isn't much change in other modes.

Question – “Are there any changes in the way of looking for jobs for farmers in your hometown?” 27% of the employees believed that the proportion of finding jobs through formal channels (direct recruiting from factories, labour departments or formal job agencies, etc.) had increased compared with the situation two years earlier. 17 percent believed the proportion had declined. About 21% believed there was not much change. 19% said, due to various reasons, they couldn’t judge how the formal channels functioned in their hometowns. 16% didn’t know there were such channels at home. This means the function and influence of formal employment channels are limited. At least, in the eyes of the farmers, the media and government departments concerned haven’t made much progress in promoting “organized flow” in the last ten years. The basic modes for farmers to get employed are still through their social networks based on their geographical and family connections.

...

If you need the full context, please leave a message on the website.