Plaintiffs from East China begin court case to retrieve an 11th-century golden statue of the Buddha that contains human remains.

Chinese villagers suing for the return of a statue they claim was stolen from their local temple have demanded that the Dutch owner disclose the identity of the disputed artifact's new holder.

The 1.2-meter-high Buddha statue, which contains mummified human remains, was bought by Oscar van Overeem, an architect and experienced art collector in Amsterdam, in 1996.

However, on Friday, Van Overeem told a court in Amsterdam that he had exchanged the statue for several Buddhist artifacts, and no longer knows where it is. He declined to name the new holder.

The plaintiffs claim the 11th-century relic was stolen from a temple in Yangchun village in the eastern province of Fujian more than 20 years ago, and that it contains the mummified remains of Zhang Gong, a revered Buddhist monk who lived during the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

They began the process of retrieval after recognizing the artwork, known as the Zhanggong Patriarch, when it was exhibited in Hungary in March 2015.

While Van Overeem conceded that the Buddha originated in Fujian, he insisted it is not the statue that was stolen from the temple in Yangchun.

The villagers said Van Overeem had previously agreed to return the statue if conditions he stipulated were met, but when negotiations failed they filed the lawsuit with the Dutch courts.

The demand was debated during the first day of the court hearing.

The case is being watched closely because it could mark the first successful retrieval of a Chinese relic via court proceedings. Previous relics have been returned to their rightful owners through diplomatic channels.

Anonymous holder

At the hearing, Van Overeem stated that the new holder of the statue is a "collector-investor-intermediary", who "is aware of the mummy controversy and political sensitivities, and prefers to remain anonymous".

When asked to disclose the holder's name, or email exchanges that would illustrate how the deal was negotiated and the conditions under which the exchange was made, he refused.

Representing the villagers, lawyer Jan Holthuis told the court that under the Dutch Civil Code such an agreement is contrary to good morals and an affront to decency and public order, and is therefore void.

He cited an email signed and submitted by Van Overeem as proof that the collector reached the exchange agreement after learning that the villagers had hired lawyers to take legal action in the Netherlands.

"By taking the statue away, the collector caused a presumption of a fraudulent act - namely preventing the enforcement of a claim to return Zhang Gong, if the court would so decide," Holthuis said.

Two weeks ago, the villagers filed a demand asking the court to require the defendant to disclose the identity of the new holder.

In response, Van Overeem asked the court to dismiss the villagers' demand immediately on formal grounds. The judge refused and ordered him to submit a statement to challenge the claim within six weeks.

"This is good. The other party has the right to make a statement on the reason why they think they cannot disclose the identity, and we can still reply to their statement. Then the judge will make a decision on it. It might take months," Holthuis told the media.

When the identity of the new holder is known, the villagers will seek to make him or her part of the legal proceedings to answer their claims that the Zhang Gong Buddha statue should return home, he added.

Identity issues

The nearly three-hour hearing was dominated by a debate over the identity of the statue. Is it Zhang Gong, the 11th-century monk who has been worshipped for generations in two Chinese villages, or not?

"It is not their statue," Van Overeem told Xinhua after the hearing.

In court he read several reports and emails and produced a CT scan to show that two characteristics of the Zhang Gong statue - a hole in one of the hands and a wobbling head - were not present in the statue he bought.

When asked about the Chinese characters that read "Liu Quan" - Zhang Gong's given name - and "Pu Zhao Tang", the name of the village temple, written on a roll of linen found in the statue, he said: "The linen was added 200, 250 years later. It is not automatic proof that it belongs to the mummy."

When the judge inquired about the possibility of seeing the Buddha to check the evidence, Van Overeem said the new holder wishes to remain anonymous.

Holthuis showed the court numerous similarities between the statue and the Zhang Gong Patriach, arguing that the villagers are entitled to have their statue returned to its original place.

"There is objective evidence that Zhang Gong is Zhang Gong. Each time, Mr Van Overeem comes back to two arguments - no hole in one hand and no loose head. But we have no independent evidence, because he did the CT scan and now the Buddha is no longer in his possession," he said.

Lawyers representing the villagers also used the argument that Dutch law states "a person is not allowed to have the corpse of an identifiable person in their possession".

Van Overeem argued that what was discovered in the statue was not a "corpse" but "human remains", because "most of the organs are absent".

Burden of proof

Holthuis argued for a "reversal of the burden of proof".

"Mr Van Overeem does not have a purchase invoice or any document to show the origin of the Buddha," Holthuis told the court. "Chinese government records do not show any export permit for this Buddha. Besides, a permit to export the Zhang Gong Buddha would never have been granted," he said.

"A comparative study of the statue for proof or return is no longer possible because of his (Overeem's) actions."

Invoking recommendations adopted by the Ekkart Committee, a Dutch government body in charge of returning looted World War II artworks that remain in the hands of the Dutch state, Holthuis argued that it is up to Van Overeem to prove that the statue is not Zhang Gong.

The committee's recommendations are recognized by the Tweede Kamer, the lower house of the Dutch parliament.

Since the villagers' ownership of the Buddha statue has been proven to a high degree of probability and Van Overeem has not provided legally convincing indications to the contrary, "it is up to Mr Van Overeem to prove that the Buddha is not Zhang Gong", Holthuis told Xinhua.

Legal standing

Other issues were also brought up in court, such as the legal standing of the Chinese villagers in Dutch courts, and whether or not Van Overeem bought the statue in good faith.

Van Overeem claimed that the "Chinese village committee is not to be referred to as a natural person or legal person" under the Dutch Code of Civil Procedure, and "the claimants should be declared inadmissible in their claims".

Holthuis later told media outlets: "We have already argued that the village committee is a special legal person under Chinese law, and there is jurisprudence or case law in the Netherlands saying that even when you do not have legal presentation in terms of a legal entity, you can still file a claim.

"A lot of issues in this case have no case law," he told Xinhua. "Each time we almost have to invent the next step. But it doesn't mean we will fail."

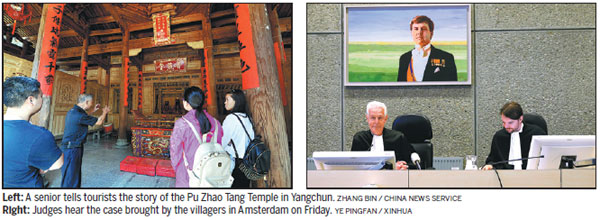

Burning incense

On Thursday evening, dozens of villagers burned incense in Pu Zhao Tang, the temple in Yangchun, and prayed for the return of the missing statue.

In 2015, the village went through official and private channels to negotiate with the Dutch collector for the return of the statue after hearing media reports that the statue being displayed at a "Mummy World" exhibition at the Hungarian Natural History Museum in the capital, Budapest.

Villager Lin Wenqing said the Buddha had been worshipped in the village temple for more than 1,000 years, and even though the statue is no longer there, the villagers still hold a prayer ritual every year on Oct 5, the Bodhidharma Buddha's birthday according to the lunar calendar.

Liu Quan, a local man who became a monk in his 20s and adopted the name Zhang Gong, won fame for helping people by treating illnesses and spreading Buddhist beliefs.

When he died at age 37, his body was mummified as he had wished, and placed inside the statue.

"Master Zhang Gong was famous as a spiritual leader, because of the help he gave to those who needed it and because of his powers of healing. Upon his death, his body was protected against rotting through herbs and other means. Thereafter, the body was protected with a layer of lacquer and covered with a layer of gold," said Liu Yushen, a lawyer registered in Beijing who provides legal support to the villagers.

"The likely wish of monk Zhang Gong was that through mummification he would continue to have a spiritual and healing power on his environment after his death, and he would certainly not have agreed that his body would become the subject of (illegal) art trade," Liu told Xinhua.

"For villagers who live in a region that was the root of Buddhism in China, mummification has a special meaning. It implies that the body of the enlightened Buddhist monk remains part of the human world, and can still be defiled after his death by external influences. From generation to generation, the statue is worshipped and the day of the monk's death is still marked with pious ceremonies."

In March 2015, hundreds of Fujian residents signed a letter addressed to Mark Rutte, prime minister of the Netherlands, pleading for the return of the statue.

The letter, written in Chinese and English, was handed to European-Chinese groups in the Netherlands, which delivered it via the Chinese embassy.

"We believe this is the Buddha we have been searching for during the past 20 years and we look forward to its return," the letter said.

Xinhua

|

The Zhang Gong Patriarch on display at the Hungarian Natural History Museum in Budapest, Hungary, in 2015.Attila Volgyi/xinhua |

|

A villager shows off the crown worn by the statue in Yangchun, Fujian province.Jiang Kehong / Xinhua |