Comment

Share the journey and more

By Qi Zhai (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-01-29 11:16

|

Large Medium Small |

There has been a lot of talk of trains: the new real-name ticketing system, the crackdown on scalpers and an estimated 210 million passengers readying to overwhelm the railway network ahead of Lunar New Year.

Everyone is focused on getting hold of elusive tickets now, but in a week's time, millions will be sharing in another collective experience - the camaraderie of the train ride.

I frequently travel the Beijing-Harbin route. As a child, I boarded the old clunker trains; by now I've upgraded to soft sleeper-only trains. Although I can well afford to take a 90-minute flight, I prefer the train, for old time's sake.

I've never had an unpleasant rail journey on my annual northeastern migrations. Taking the train has always been a homely and happy experience, which says a lot about the people on it. Isn't it true that when large numbers of people are confined in a small space for a prolonged period of time, their true characters shine through?

Some agreeable and predictable aspects of train life put me at ease. For a start, while boarding the Eurostar or the Amtrak has passengers preoccupied with reaching point B, boarding a Chinese train is a chance to indulge in our national obsession with food.

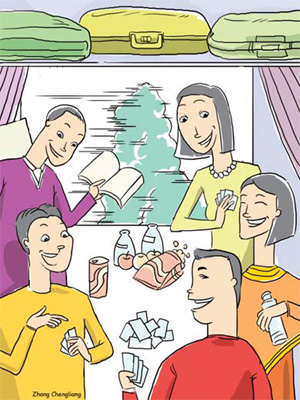

Foreign guests whom I've enthusiastically dragged onto Chinese trains often remark on the amount of snacks around. Regardless of how long the trip or what time of day one travels, we stock up for the train like we are going on a wilderness expedition. The habitual train traveler locates his seat and immediately spreads out a buffet of sausages, pickles, crackers, sunflower seeds, and of course, Master Kang instant noodles. What better way to make friends with fellow passengers than by sharing grub?

As the journey gets going, I can also rely on another kind of sharing to take place: the over-sharing of information. I've smugly eavesdropped on many conversations among foreigners discussing the Chinese habit of inquiring and divulging too much personal information.

I can empathize with their complaint. Hardly an hour into most train rides, my neighbors will have gone to the heart of matters: How old am I? Married or single? What do I do for a living? What do my parents do? How much do we all make? Having now a Western preference for discretion, I usually reply with vague "hmm's" as curious aunties throw out unabashed guesstimates about me. But I know it's all in good humor for they will soon bare their family accounts to me without prompting.

From there, the train ride feels less like a mutual imposition among strangers and rather more like an afternoon chatting with intimates. Topics vary, but inevitably conversations touch on suzhi, a word for which I've yet to find a satisfactory English translation. We, as a nation, are perpetually perturbed with our lack of admirable "quality". So, the poorer among the travelers laud the elevated suzhi of urbanites, while cosmopolitan Beijingers sing praises of exceptional suzhi observed among foreigners.

After years of careful observation, I find that, as badly as we may display our collective suzhi in hectic everyday life, I've yet to come across lamentable suzhi in the train cars. Sure, old men run down the aisles in their long johns and bunk mates occasionally have the indecency to snore, but a spirit of sharing and courtesy has accompanied my every trip. As millions head for the tracks next week, I am sure they will be offering food, helping with luggage, and doling out concerned advice to those sharing their journey. And that is perhaps our truest national character.