Profile

Khemit's 'fight or flight' adventures

By Qi Zhai (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-03-03 14:03

|

Large Medium Small |

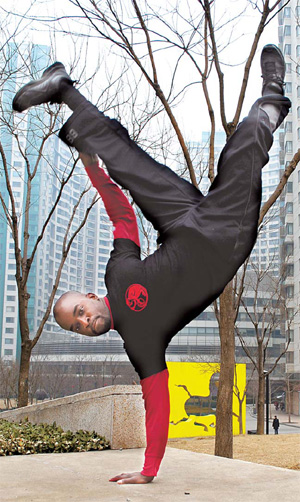

Khemit Bailey is a 28-year-old American who has lived in Beijing for more than a year. He tells METRO what it's like to teach parkour (which some call extreme walking), an urban sport that involves clambering and jumping on, off and over obstacles in the fastest and most efficient method possible.

METRO: Wikipedia says parkour can be compared with martial arts, but parkour practitioners are developing skills to run away from people, rather than to fight them. What are you trying to run away from?

|

American parkour instructor Khemit Bailey performs a single handstand. Qi Zhai / for China Daily |

You learn the ability to do something but you don't necessarily have to do it. Parkour encompasses the idea of fight or flight. You're either chasing down somebody for a fight or running away from a dangerous situation. If I had to run away from something it would be a ninja.

METRO: Why a ninja?

A: If you watch old movies, any scenes that have to do with getting around swiftly pretty much involve ninjas and superheroes. I wouldn't mind running away from a superhero, but I kind of like ninjas, because they're the embodiment of cool.

METRO: "Ninjas are the embodiment of cool?" Please elaborate.

A: Ninjas are fighting machines and they're well-versed in parkour, although they don't call it that. If you can escape from ninjas, you can escape from anything.

METRO: Are there different forms of chasing and running away?

A: There's an important distinction between parkour and free running. In China, we call everything "paoku", but actually they are different. Parkour is all about utility - getting from place to place as quickly and as efficiently as possible.

There are no extraneous movements in parkour. Nothing is done for aesthetic value. Then there's free running, which is very similar but is all about style. Free runners do a lot of front flips, which look awesome but are not very useful.

METRO: You mean I can't just escape my worst enemy by continuously front flipping?

A: You certainly could if your worst enemy were a toddler, or if you were flipping down a mountain.

METRO: Speaking of utility, what have you used parkour for in real life?

A: I actually use it all the time. I'm the kind of person who likes to jump over a fence rather than look for an entrance. I'm lazy. But the main appeal of parkour for me is that it changes the way I look at the world. Not doing parkour, I see things around me that look like barriers and seem insurmountable. From doing parkour, I started thinking of ways to get around obstacles. It's a way of thinking about life.

METRO: So, you see everything as a barrier do you feel the urge to jump over me right now?

A: I don't want to jump over you right now. But that's not to say that I won't later.

METRO: What's the history of parkour?

A: David Belle is considered the founder of parkour. He and a group of friends developed it in France about 15 years ago. Where they were growing up there wasn't much to do. So they tried to jump over things and have fun.

They saw potential there and developed it into a system of techniques that you could teach to people who aren't naturally athletic.

The other big name is Sbastien Foucan, a friend of David Belle's who founded the spinoff sport, free running. The James Bond movie, Casino Royale, is what sparked these sports' popularity.

METRO: As an instructor what is the hardest thing about teaching parkour?

A: It's the fear. Some basic movements employ balance, which is difficult. Certain jumps, such as the dash vault (a jump done with legs first), are made more difficult by the fear of falling backwards.

METRO: You teach children too. Do they pick it up easier because they have no fear?

A: Yes and no. Most of my kids are aged 10 to 15. Kids are more athletic and mentally flexible, but their attention span is short. The temptation they have to jump over stuff instead of practicing the moves is really strong. I prefer to teach adults.

METRO: What kind of parent sends their kids to learn parkour?

A: An awesome parent. Kids are jumping over things anyways and teaching them how to do it safely is useful.

METRO: What type of person is attracted to parkour?

A: You'd be surprised. Some of my students are really overweight. My oldest student is 45 years old. The parkour "type" is someone who is open-minded and attracted to movement.

METRO: Do people think you're crazy when you show up at the park and start jumping over random things?

A: I try not to do it alone. In a group you're less crazy. But yes, if I am alone doing it, people think I'm crazy.