Profile

Spanning the Straits with a tie to home

By Wang Wen and Qin Zhongwei (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-03-22 08:09

|

Large Medium Small |

|

Producer Wang Wei-chung, an icon of televisions in Taiwan, speaks Beijing dialect and says the city is his home. Zou hong / China Daily |

Taiwan's playwright Wang Wei-chung talks to METRO reporters Wang Wen and Qin Zhongwei about documenting life in dependents' villages

He bills himself as a "super producer" and explains that he was like a neighbor of every audience in Taiwan. When he walks the streets, passers-by greet him. He is Wang Wei-chung , an icon of televisions in Taiwan.

Wang brought his play The Village, which was produced by Wang and renowned film director Stan Lai in Taiwan, to Beijing last month.

The play, which debuted in Taiwan in 2008, has aroused Taiwan people's attention for military dependents' villages (Juancun), the communities of the families of Kuomintang soldiers across the island province.

Wang, who grew up in such a dependent's village in Chiayi, says the play was not his only way to present the dependent's village. His parents left for Taiwan from Beijing in 1949 and settled on the island. The village became their home.

"Finally I could bring my parents' story back to Beijing - our home," Wang said.

Wang has worked in the broadcast industry for more than 30 years. He is a prolific TV producer and the brain behind a number of popular programs, such as Guess Show and One Million Star. Now he owns an entertainment production company, which produces about 80 percent of the TV shows in Taiwan.

Q: What do you mean when you say this time you can bring The Village back home?

A: The story of The Village actually started in Beijing. My parents left Beijing for Taiwan in 1949, and I grew up as a witness to see how my father lived with other villagers and they helped each other.

Now I am working in show business and can take the advantage of my job to tell the story onstage. And I am bringing it back to Beijing this time to let my relatives see the story. For director Lai and the actors, it is a good play. But to me, it is more than that.

Q: You have visited Beijing many times since 1988. What's your impression of Beijing as told by your parents?

A: Well, it is quite subtle but moving. I grew up in Chiayi city, but as a child I knew my hometown was Beiping. But I just had a very vague impression and some details from my parents.

For example, the city is sometimes windy and people need to wear masks against sandstorms. They told me about their courtyard house, its small pond, the chubby girl and the old dog, as well as the Douyacai hutong where they used to live, and the old theater where they used to hang out and date.

They also told me about my grandma and showed me her photo. But that's basically all what I knew.

All those details are scattered and hard to put together due to the fact that two sides cannot contact each other.

For me, the mainland is like a relative too far away, and "he" is in black-and-white color, wearing a long and gray coat. And grandma to me is just who is in the old photo, no more else.

We had hoped to visit her one day, but the dream did not come true until we were allowed to return to visit our relatives temporarily in 1987.

Q: So what's your impression when you first came back to Beijing and see the city in person?

A: I came to Beijing shortly after my mother visited her mother in 1988. I remember very clearly the blue sky and the Third Ring Road, which was still under construction. I traveled all the way to Zuojiazhuang from the airport and found my grandma's home, based on the address my mother told me. My mom cried at once when she heard me knocking on the door. And I saw my grandma sitting on the bed.

Beijing is familiar but afar. It is hometown, but not really. I speak the Beijing dialect in Taiwan. But here people all speak in the same way. And my uncle looked just like my cousin. That's my impression. It is subtle and interesting. But the word "interesting" is difficult to explain.

Q: Is the Beijing in 1988 different from the picture that was in your brain?

A: I studied journalism in college, so I thought people like me were more skillful in collecting information. I went to Beijing when I was 31. Before that I had traveled around the world.

Therefore, I thought I would know Beijing quite well. But actually it was the opposite.

In the 1980s the material life in the city was not quite adequate, but it is a magnificent ancient city with a long history. I went to the Summer Palace, the Lama Temple, the Great Wall and the Forbidden City and they were impressive. It is hard to pick a word to explain that feeling.

Q: Do you see any changes in the city over the years?

A: Beijing has changed so much. At a quick glance, in some corners, it just looks like Tokyo, New York or any other metropolis. But it used to be unlike this. The transformation may be inevitable because of the progress being made and the fact that time is always moving forward. But people will definitely be melancholy and miss the old Beijing, especially the baby boomer generation born after the 1950s.

Q: How much of the story onstage is based on your own experience?

A: When I had a rough idea on a play about dependent's villages, I told Stan Lai and shared many of my stories with him, more than a hundred, I think. He also had some stories from those who lived in the dependent's villages as well and got some other stories. My stories probably accounted for 80 percent of the whole play.

The stories span the lives of three families over 50 years. Actually, there are several hundreds of such villages in Taiwan where the low-level soldiers and their families live, so basically we have shared the same living environment. The culture, the architecture are all similar.

Q: Among those stories, which do you think is most touching?

A: Lao Zhao, the figure that Chu Chung-heng portrays, is very like my father. My father, then a 19-year-old, and my mother, younger than 16 at that time, arrived in Taiwan when they were still not grown-ups, and established a family in an unfamiliar place.

You can imagine that life was not easy at the very beginning. My mother had four children. I was the youngest and born when she was 25. She spent all her life raising her children. My father was a driver.

They didn't set specific life goals but they were homesick. They had never thought about the value of their lives. Their only hope was to come back to the mainland in the future. But as they had their children and grew older, the hope waned. My father passed away before he could come back.

The figure on the stage is just like my father, an old soldier whose whole life was defined by fleeing and relocating. The character's dialogue still touches me even now.

Q: Has your life in the village helped you learn well about people from different provinces and their accents?

A: The people living in the dependent's village are soldiers coming from everywhere on the mainland, and some Taiwan natives who married into the village. So we took a great opportunity to know various ethnic minorities and their languages. It is very helpful for me to understand Chinese culture in a complete sense. The environment where I grew up imposes a lifetime influence on me.

Q: Do you expect the culture of the dependent's village could be understood and spread in the mainland?

A: I do not know. The responses of audiences can never be forecast. However, I think from this play or my other TV shows and dramas, some people begin to think that the culture of the dependent's village is significant. I do not know whether the culture could create a huge influence in the mainland, but the seeds of the culture has been sowed already, like what I do now. That culture is part of the modern history of China.

Q: Why did you shift your work from TV shows to focusing on a dependent's village?

A: Normally people start to work for life and then do interesting things after making some money. When people grow up and resolve the issue of survival, we want to do something, especially those of us born during the baby boom. Many of us are in our fifties and sixties now but still remember the old days. This is true all over the world. That is why Romantic Life and In the Heat of the Sun were produced.

The younger generation will follow suit when you are old. It is difficult to explain how you will remember the old days in the future. What you see now are only concrete buildings. What we saw were more colorful and various. It is like a man whose most wonderful period was adolescence. It is easy to remember the things in adolescence, such as romance.

Q: Do you know many audiences on the mainland know Taiwan through your TV shows and dramas?

A: If it is so, I am very happy. I do not dare to say what influence I have brought to audiences on the mainland. I have worked in broadcasting for more than 30 years. Happiness is my corporate culture. I hope I can lead a happy and interesting life. I've enjoyed sharing my happiness with others.

Q: Do you have any plan to do some programs in Beijing?

A: I don't know. First of all, opportunity is needed. Second, the cultural industry between the mainland and Taiwan is encouraged, but there are still some limitations. However, we are of the same race and share the same language.

We have some differences, which I hope could create interesting things. I have a company to make puppetry plays in Shanxi province. The performances have won many prizes all over the world. It is what I am doing on the mainland. I hope, of course, could do more interesting things on the mainland.

|

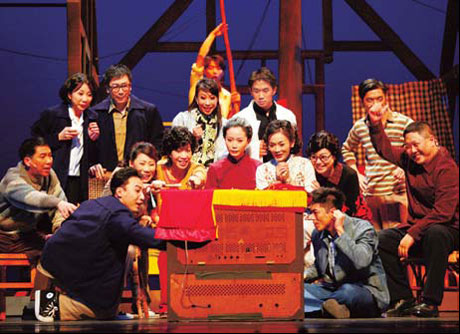

The play The Village, produced by Wang Wei-chung and Stan Lai, came to Beijing last month. Provided to China Daily |