Focus

'I wish I could sit for my exams here'

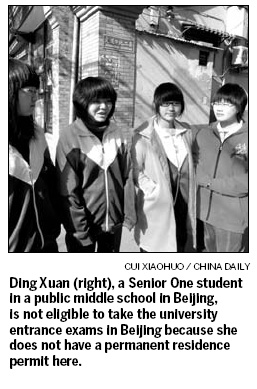

By Cui Xiaohuo (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-04-16 08:24

|

Large Medium Small |

Ding Xuan was bewildered when her head teacher asked her last summer to give up her Best Student Award in favor of one of her classmates.

"It took me a while to understand what the teacher was saying," said the 15-year-old, who does not have a Beijing permanent residence permit although she's lived in the city from the age of six.

"I was told to give up the award because a migrant student with a Best Student Award would not give the school a bonus in the high school entrance exam.

"However, a local student with the same award would be able to, the teacher told me."

Despite Ding's grades being the top in her class in all her courses, she was given no alternative. Ding said she often finds herself a victim of the restrictions placed by Beijing's education system on migrant workers' children.

The group, up to one million families citywide, has faced difficulties in every phase of their children's education, from elementary school allocations to university entrance exams.

Ding, a Senior One student in a public middle school in Beijing, is also facing the problem of not being eligible to take the university entrance exams in Beijing in two years, but has to do it in her hometown of Wenzhou, Zhejiang province.

"I wish I could take the exams here," Ding said.

Zhang Yuhan, Ding's classmate who was born in Beijing, said she also believed her friend should have equal rights to sit for university exams with local students.

"Why should there be a difference? She also lives in Beijing and she has one of the best grades in the class," said Zhang.

Ding came to Beijing with her parents to start her primary school after her parents paid extra "sponsoring fees" to a local school near the populated Jiaodaokou area in Dongcheng district.

For the past nine years, her parents have run private businesses such as tea shops to fund their daughter's 10,000-yuan schooling costs and the additional 10,000-yuan "sponsorship fee" every year.

But even so, Ding is still considered "alien" because she had no permanent residence, or hukou, permit.

Her mother, Zhang Dongcui, has been talking to education officials, headmasters and the media to help get her daughter into decent public schools. Ding spent two years in a private primary school, four years in a public primary school and another three years in a public junior middle school in the past nine years.

"There were both good times and bad times," said Zhang, 53, who described her daughter's journey as a zig-zag road. "There are hundreds of thousands of migrant children like Ding in Beijing."

Huang Xin, another student whose migrant worker parents paid thousands of yuan a year to have her study at a public middle school, said she wishes her parents, who sell water products in a local supermarket, didn't have to pay sponsoring fees to keep her in school.

"I hope I can have equal rights with my classmates," the 12-year-old said.

"All we hope for is an equal chance for our children to take exams," said Huang Jinqiang, father of Huang Xin. "I don't think that's too much to ask."