Comment

Does slogan publicity work?

By Qi Zhai (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-04-16 08:25

|

Large Medium Small |

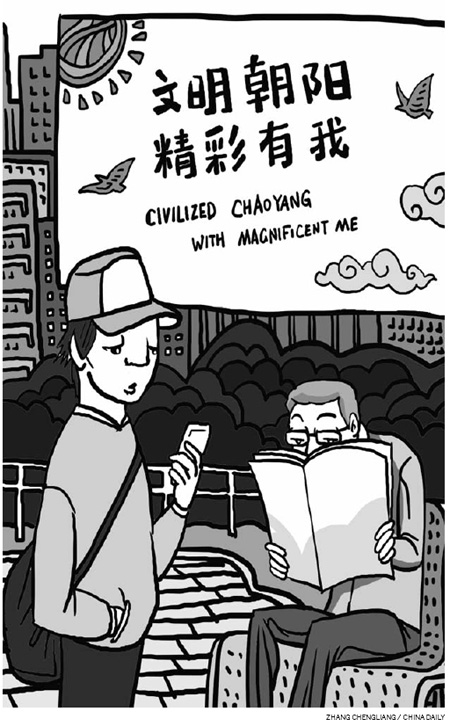

Since March, a freakishly cheerful cartoon character girl has been beaming down at passing traffic from oversized billboards on Beijing's east side. Her name is Luo Baby and, with a jolly hop, she promotes Chaoyang's latest public service slogan: "Civilized Chaoyang with Magnificent Me".

Images of this latest propaganda incarnation are now ubiquitous in neighborhoods east of Chaoyangmen. At intersections, along sidewalks, and atop residential buildings, Luo Baby's constant smile makes me wonder, "Does this stuff still work any more?" This thought is usually followed by another worthy question, "Couldn't the district government have hired an English proofreader to iron out the syntactical awkwardness?".

The "Civilized Chaoyang with Magnificent Me" campaign appears to have kicked off on March 1, from what I could gather on the district government's information smorgasbord of a homepage. The website doesn't tell me much else about the campaign: what it seeks to accomplish, how long it will last, and why it was necessary to have clumsy bilingual slogans. But, I did find a uselessly entertaining page featuring English translations of Chinese signage, which decodes handy instructions like, "If the alarm beeps after you pay, please go to the counter with purchased books for re-demagnetization."

Why the sudden surge of enthusiasm for slogans? March 5 marked the 47th anniversary of Chairman Mao's anointment of Lei Feng as the model of an upright Chinese citizen. From that day on, Lei Feng, a common soldier, became a national legend. And the slogan Mao assigned to him, "Emulate Lei Feng, a good model", became as indispensable to our contemporary lingo as "Good good study, day day up."

In commemoration of March 5, 1963, Chaoyang district launched its "Civilized Chaoyang with Magnificent Me" campaign. Other coordinated neighborhood-level initiatives, like the "Build a Civilized City, Smiling Hujialou" mini-campaign and a civility petition, supposedly signed by 10,000 Beijingers, followed.

Slogans and propaganda have a long and illustrious history in China. Their most masterful applications took place during the Mao era. Regardless of where your ideological sympathies lie, it's difficult to deny that Chinese propagandists were skillful at fanning emotions in the war-torn days. Even though the Shangganling Battle was fought decades before I was born, I struggle to push back tears every time I catch a rerun of the black-and-white film rendition. When the music swells and soldiers selflessly jostle to become martyrs for the cause in dark underground tunnels, I weep for the glorious self-sacrifice that will ensue.

During the decades of peace that followed, hand-painted slogans in broad white strokes decorated walls all around the countryside and in old urban neighborhoods. The sometimes cleverly catchy slogans extolled the virtues of family planning, paying your taxes and sweeping out pornography.

As China developed, the slogan-based method of educating and influencing the public was used less and less. With red-brick buildings continuously demolished to make way for skyscrapers, it sometimes feels as though all that remains of slogan publicity is the fading white paint peeking through piles of rubble.

Yet, in truth, slogan publicity didn't disappear. It was reinvented in glossy graphics and technicolor. It was on full display leading into the Olympics, when furry cartoon mascots broadcast civilized reminders all around Beijing.

Does slogan publicity still work? It seems to have worked for the Olympics. Waiting at the bus stop is immeasurably more bearable now than it was three years ago, when I always ended up pushed off the curb or squashed against someone's hefty bag. One seemingly unchangeable habit - cutting in line - did change for the better.

But was the improved behavior on the streets of Beijing all thanks to the slogans? I think not. The collective national pride, eagerness and the coordinated efforts of celebrities and statesman, reinforced the message during seven years of anticipation.

So, how will the merry "Civilized Chaoyang with Magnificent Me" campaign fare? Not well, says this skeptic. It being entirely unclear what change this vaguely broad slogan is intended to induce, I'm not sure how we can observe its success. Without a frenzied countdown to an event of epic proportion, people are also not motivated to pay attention. And, finally, when a car dangerously cuts me off on the pedestrian crosswalk, looking up to see Luo Baby's annoying smile just drives home the irony.