Tales of China that dazzled a Korean king

By Zhao Xu (China Daily Europe) Updated: 2017-02-19 15:24Winds that drove a civil servant off course also blew him and his story into history

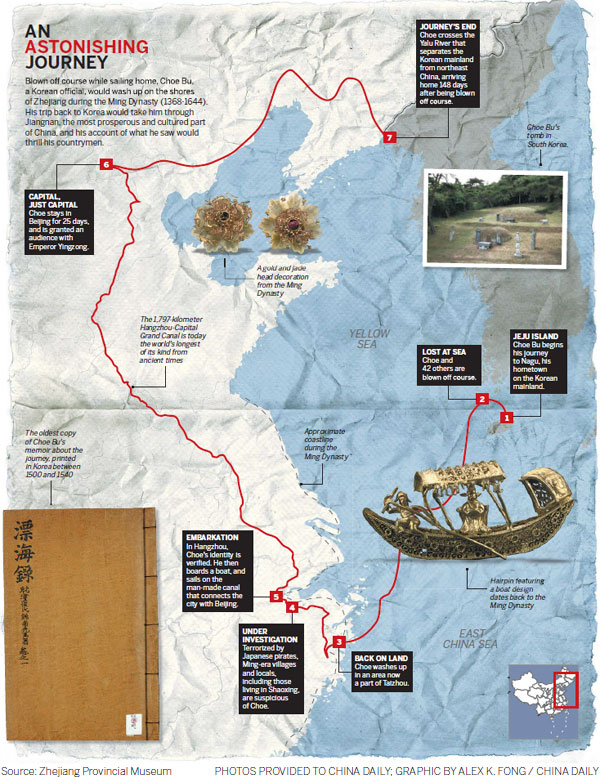

It took Choe Bu, a Korean living in the late 15th century, 135 days to make the trek from a tiny town on China's eastern coast to Beijing, capital of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), and then back to his motherland.

The journey awed Choe's contemporaries, including the Korean king, who was so impressed that he decreed that a memoir of the feat immediately be committed to writing. The 50,000 words, written in Chinese and titled Journey Across the Sea, have in turn immortalized Choe's remarkable experience for his generation and those that followed.

Most recently the memoir has spawned an exhibition, underwritten by the Zhejiang Provincial Museum and the Jeju National Museum. The hundreds of exhibits, from both China and the Republic of Korea, seek to illustrate, in glittering jewelry, fragile fabric and ancient scrolls, the highly descriptive lines that Choe penned more than 500 years ago.

Its goals are more ambitious still: to fill the gap in the imagination of modern viewers. With antiques pulled from various levels of museums across Zhejiang province, the exhibition amounts to a comprehensive review of life in that part of China - known as Jiangnan, or "area south of the Yangtze River" - during the 15th century.

Today, a viewer can sample the best of Chinese culture from the 15th century without having to first spend 13 days on choppy seas.

"That was how Choe got to China - by boat," says Ni Yi, curator of the exhibition, his book in her hand. Ni spent five months retracing Choe's journey.

"In 1487, Choe, a government official, was posted to Jeju, an island separated from the Korean mainland by the Jeju Strait and from China by the Yellow Sea," Ni says. "Shortly after his appointment, news arrived that his father had died back home. So in early 1488 he boarded a ship that was to take him to Naju, his hometown on the Korean mainland. With him were another 42 people."

But instead of taking Choe home, the ship was caught in strong winds and began heading toward China. Thirteen days after leaving Jeju, the ship was washed ashore at what today is Sanmen on Zhejiang's coast.

"From the outset the journey was an adventure," Ni says.

Locals found and fed Choe, but he soon realized he had another fight on his hands after battling the forces of nature: He now had to prove to his rescuers his true identity.

"In the Ming era, villages in coastal Zhejiang were frequently harassed and pillaged by Wako, or Japanese pirates," Ni says. "Fearing that Choe and his company might be pirates in disguise, the villagers, kind and generous as they were, sent the group off on an overnight journey to the nearest checkpoint - under escort, of course."

For the next month Choe found himself under serious investigation twice more, in Shaoxing, and then in Hangzhou, capital of Zhejiang.

However, judging by his account, the suspicion that surrounded Choe en route to Hangzhou failed to dispel his good spirits or prevent him from soaking up all the sights and sounds of Jiangnan, the most prosperous and cultured part of China.

(In his memoir, Choe did not complain of his treatment, only lamenting about the fear and anxiety the Japanese pirates had instilled in the hearts of the locals.)

Between June and November last year, Ni traveled to many of those places, trying to match the world she saw with Choe's descriptions. Her journey is encapsulated in a 15-minute mini-documentary on view in the exhibition.

"While in Yaozhu, one of Choe's stops, I instantly recognized the pillar-like mountain mentioned in his book. And the water at Daxiba - even after so many years, I could still envision the torrents that the locals tried so hard to tame by building weirs. Moments like these were miraculous, instantly sucking you into a time tunnel. But of course, most places have changed beyond recognition."

In his book, Choe marveled at the abundance and majesty of the natural beauty he came across, from architecture to art. A meticulous chronicler, he appeared alert to any information that might be of the slightest interest to his king, for example, city layout, the construction of dams, waterways and houses.

He was also keen to record more mundane detail - for example, giving a head-to-toe description of the various dress styles of the time.

However, it was the cultural life the locals enjoyed that captivated the man who prided himself on being a member of the literati in his native country.

"People here make studying their job," he wrote admiringly.

The exhibition itself offers bountiful evidence of the cultural kinship between China and Korea in the 15th and 16th centuries, Ni says.

"Confucianism provided the guiding principles of morality for Korean society at the time. The educated, including the king and his court, all wrote in Chinese."

In fact, during Choe's entire stay, the most-often asked question from his Chinese hosts was: "Can you write a poem?" Of course, he did not disappoint them.

Fortunately for Choe and those who were with him, the identity issue was finally solved after they arrived in Hangzhou, a city richly endowed with natural beauty and steeped in China's literary tradition.

From Hangzhou, Choe boarded a ship and for the next 44 days traveled the entire length of the man-made canal connecting Hangzhou with Beijing. The 1,797-kilometer Hangzhou-Capital Grand Canal is today the world's longest of its kind from ancient times. It was built mainly in the late 6th and early 7th centuries, 900 years before Choe's visit.

Arriving in Beijing by the end of March 1488, Choe was granted an audience with Emperor Yingzong. He stayed in the capital for 25 days before heading home overland. On June 4 of the lunar calendar in 1488 Choe and his entourage crossed the Yalu River, which separates the Korean mainland from northeast China. Finally, after 135 days and nights, Choe found himself standing on the doorstep of his homeland.

However, he was not about to forget his time in China; nor indeed would his king allow that to happen. So even before Choe began attending to his father's long-delayed funeral, the Korean ruler, Yi Hyeol, made sure that Choe wrote down everything he had seen, heard and experienced.

"Throughout the Ming Dynasty and the following Qing Dynasty, Korea was in very close contact with China, sending envoys to the Chinese court several times a year," Ni says. "Between them, these missions to China yielded nearly 650 different accounts. However, rather than diminishing the historic value of Choe's writings, all the others only helped to increase the prestige of his version.

"That's because the Ming Dynasty moved its capital from Nanjing to Beijing in the early 15th century, during the reign of Emperor Chengzu. Since then, all royal envoys from Korea (the Ming rulers largely banned commercial exchanges between China and the outside world) went directly overland from Seoul to Beijing, through northeastern China. Earlier they had taken the sea route to Nanjing, which is part of Jiangnan."

So by the time Choe landed in Zhejiang, it had been about 70 years since the last Korean envoy visited. In the meantime the most fertile land of China - culturally and agriculturally - had become a mystery to many Koreans, who still revered the literary and philosophical traditions of their neighbor.

That explains the eagerness of the Korean king to be the details of Choe's travels.

"Before Choe, there had been Korean fishermen who had similar experiences, but they were largely illiterate, so no record was left," Ni says.

On view at the exhibition is the oldest copy of Choe's memoir in existence today, printed sometime between 1500 and 1540 using movable copper type.

Not far away is a Japanese Edo-period (1603-1868) translation of Choe's book, published in 1769 in four volumes. Interest in China was growing in Japan and Choe's book had certainly done its part to fuel it.

Choe died in 1504, aged 51, executed on the order of Yeonsangun, a tyrannical and somewhat tragic king who was avenging the death of his own birth mother that had occurred two decades earlier.

Yeonsangun was deposed two years later by his half-brother, and the new king posthumously rehabilitated Choe, who was given a proper burial in his hometown.

"Throughout my research, I could feel the pride Choe was able to arouse in his compatriots, who know about his story, even today," Ni says. "Believe it or not, university professors, students and amateur historians come to China from South Korea to trace his footsteps."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

- 'Cooperation is complementary'

- Worldwide manhunt nets 50th fugitive

- China-Japan meet seeks cooperation

- Agency ensuring natural gas supply

- Global manhunt sees China catch its 50th fugitive

- Call for 'Red Boat Spirit' a noble goal, official says

- China 'open to world' of foreign talent

- Free trade studies agreed on as Li meets with Canadian PM Trudeau

- Emojis on austerity rules from top anti-graft authority go viral

- Xi: All aboard internet express