It's just a number, isn't it?

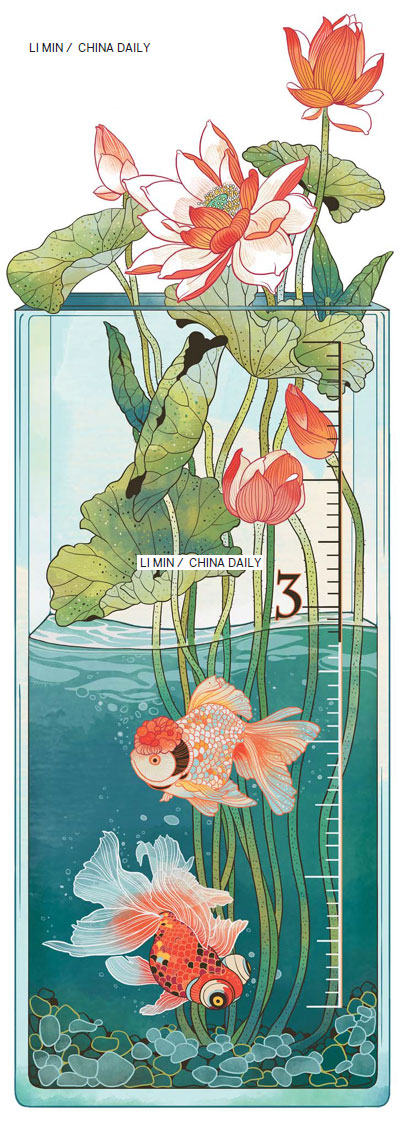

By Andrew Moody (China Daily Europe) Updated: 2017-02-26 15:06As China's foreign exchange reserves fall below $3 trillion mark, experts say there is little need for concern

Is China losing its financial firepower? The world's second-largest economy's foreign exchange reserves fell below the $3 trillion mark for the first time in nearly six years in January.

The reserves - which have a large but unspecified component of US dollar-backed securities as well as those in euros and other currencies - are often seen as China's big insurance policy.

Whatever misfortune may befall its economy, the argument goes, the reserves provide the ammunition to deal with it.

They are also often viewed as assets that can be set against the country's massive future liabilities, such as providing a modern healthcare and social welfare system, by being a potential source of financial support for any future fiscal deficit.

January's fall to $2.998 trillion - the lowest level since February 2011 - is the latest monthly drop as a result of the People's Bank of China's 18-month rearguard action to preserve the value of the yuan by selling reserves.

The currency has been under pressure since the central bank announced a new exchange rate mechanism for the currency in August 2015.

The January figure - although taking the reserves below what has been seen as the totemic $3 trillion mark - was also, however, encouraging evidence that the rate of depletion is slowing down. The reserves fell by just $12.3 billion - the slowest decline in seven months - compared to $41 billion in December.

This deceleration suggested that some of the measures taken by the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), the government agency that controls foreign exchange movements, to tighten up on capital outflows are beginning to have an effect.

Jeremy Stevens, Beijing-based China economist at Standard Bank, Africa's largest bank, does not believe the fall in China's foreign exchange reserves means China is in a weaker position to defend itself against any external shock.

According to IMF criteria relating to levels of exports, money supply and debt, China should hold a minimum of $2.7 trillion of foreign exchange reserves.

"This is too much and does not really make sense for China. It isn't Angola, and it doesn't need the same proportions and metrics. Unlike a country like Venezuela, for example, its exports are not volatile commodities," he says.

"I think a safe level for China would be around $1.8 trillion, and China is well above that at present."

Despite the recent falls, China still holds the world's largest foreign exchange reserves.

According to IMF data, Japan, the world's third-largest economy, has the second-largest amount with $1.24 trillion, followed by Switzerland with $685.56 billion and Saudi Arabia $535.90 billion.

Developed countries do not tend to rely on such reserves. The United States, whose own currency is overwhelmingly the main global reserve unit, has the 20th-largest with just $116.2 billion, despite also being the world's largest economy.

The United Kingdom has the 14th-largest with $163.5 billion and the eurozone countries of Germany ($200.4 billion), France ($153.9 billion) and Italy ($143.2 billion) are in 11th, 15th and 16th places, respectively.

Zhu Ning, deputy director of the National Institute of Financial Research at Tsinghua University, says there is no need for the major developed economies to hold reserves.

"This is particularly the case for the United States, whose currency is held by everyone else as the main global reserve currency. The eurozone economies do not need to hold large amounts because of the arrangements within the European Central Bank," he says.

"Those that have the biggest reserves tend to be oil-rich countries that accumulate them through their huge oil exports."

Xu Bin, professor of economics and finance at the China Europe International Business School, says the holding of foreign exchange reserves became important for many developing countries following the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s.

"After the crisis, almost all East Asian countries, including China, began to accumulate large amounts of foreign exchange reserves. They were afraid the next time an attack came they wouldn't have the weapons and bullets to deal with it."

It was after China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001 that the country began to accumulate major foreign exchange reserves, growing them steadily for almost a decade and half before peaking at just under $4 trillion in June 2014, apart from a three-month blip when they fell at the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008.

Companies selling their largely manufactured goods abroad accumulated huge amounts of foreign currency which they converted into Chinese currency within the Chinese banking system.

Xu says having large stockpiles of reserves is not the benefit to the economy that many assume, since it results in too much Chinese currency (which the reserves have to be converted into) sloshing around, creating inflation.

"Having too much foreign currency over the past 16 or 17 years has driven up the money supply and led to too much liquidity, which has created these asset bubbles," he says.

The major question now is whether the fall in the value of China's reserves, by almost $1 trillion over the past year, is cause for concern.

"Falling through the $3 trillion mark - which was the level they should not fall below - does not carry that much significance," says Zhu at Tsinghua, also the author of China's Guaranteed Bubble.

"It is the quite rapid decline, despite increasingly stronger capital outflows, that is not reassuring."

Stevens at Standard Bank says the problem the authorities have is that because they are such large holders of dollar-denominated and other assets, if they continue to sell them to preserve the value of the currency, the value of their existing reserves will fall.

"If they were to unwind positions, the market would react and the value of the assets they hold would fall," he says.

"Perception can become reality. Burn rates accelerate, markets freeze and values fall. And suddenly what was $2.9 trillion in a normal market becomes much less in reality."

Some believe there would be risks at this stage if China were to lose a large chunk of its get-out-of-trouble buffer reserve.

He Weiwen, senior fellow at the Center for China and Globalization, China's leading independent think tank based in Beijing, believes the significance of this is often exaggerated.

"China is not just reliant on its foreign exchange reserves. It has many other tangible assets, including more than $1 trillion of investment stock overseas," he says.

"There is also an issue as to how much of the foreign reserves sold have actually left the country. The central bank has sold some of them to businesses and individuals who are still in the country."

Zhu at Tsinghua believes the level of reserves does offer ballast, particularly in relation to the fiscal budget.

"Foreign reserves are like the bank of last resort for the fiscal situation. Your actual fiscal position will not be scrutinized that much because everyone thinks whatever trouble you are in, it can be solved by using your foreign exchange reserves."

One of the concerns about the recent imposition of capital controls has been its impact on companies going abroad.

Helan Hai, CEO of the Made in Africa Initiative, a UN nongovernmental organization that advises African governments on industrialization and investment, says it has not had a significant impact on companies investing in Africa.

She says that one of the key performance indicators that Chinese state-owned companies are now assessed by is their ability to bring foreign exchange back into the country.

"It is not just about profit anymore but bringing investment income back into China, and that is why they are very active and want to invest abroad in places like Africa."

Xu at CEIBS believes that some of the debate about China's foreign exchange reserves is often too polarized.

"People talk as though you have only two choices - either deplete the reserves or let the exchange rate fall. It is just too extreme. There is a third dimension to this, which is the greater internationalization of the RMB."

Moves to open up China's capital markets and allow greater convertibility of the currency have to some extent been put on hold as policymakers have focused on stabilizing its level.

Xu says a more open capital market would reduce reliance on China needing to hold large amounts of foreign reserves.

"Over the next 10 years I believe there will be bigger steps toward more opening-up. RMB assets will become increasingly attractive to international investors. Once the currency becomes fully convertible, the level of the country's foreign reserves will no longer be an issue."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

- 'Cooperation is complementary'

- Worldwide manhunt nets 50th fugitive

- China-Japan meet seeks cooperation

- Agency ensuring natural gas supply

- Global manhunt sees China catch its 50th fugitive

- Call for 'Red Boat Spirit' a noble goal, official says

- China 'open to world' of foreign talent

- Free trade studies agreed on as Li meets with Canadian PM Trudeau

- Emojis on austerity rules from top anti-graft authority go viral

- Xi: All aboard internet express