WINNING A BATTLE IN WAR ON POVERTY

By LI LEI, PALDEN NYIMA and DAQIONG in Lhasa (CHINA DAILY) Updated: 2020-01-01 00:00On Dec 23, many Chinese people felt excited and proud by the news that the local government in the Tibet autonomous region had decided to strip 19 counties of their poverty labels, after 55 Tibetan counties cast off such labels in 2018.

This means that the vast and sparsely populated region, known for its snowcapped mountains, roaming antelopes and yaks, no longer has counties with registered poverty rates of 3 percent or higher.

In the nationwide battle against absolute poverty, which picked up momentum in 2012, the central authorities created two major indexes to help track the progress.

One is the head count of rural poor, who are defined as people living on less than 2,300 yuan ($328) a year. The bench mark was set in 2011 and is adjusted annually for inflation. The other index involves counting the number of counties categorized as impoverished, which reflects the level of regional poverty.

By stripping the remaining 19 counties of the impoverished label, Tibet has made good progress in eliminating regional poverty-a giant leap toward the zero-poverty target.

"It was an iconic episode in the overall poverty reduction work in China," said Wang Sangui, a prominent rural affairs scholar and a professor at Renmin University of China. "Tibet used to be among the regions hardest hit by extreme poverty, and by delisting all its impoverished counties, China is a step closer to xiaokang shehui," he said, referring to the Communist Party's pledge to establish a moderately prosperous society in all respects before the celebration of its centenary in 2021.

With a population of 3.4 million people predominantly of ethnic Tibetan heritage, Tibet accounts for a majority of the Three Areas and Three Prefectures, jargon that officials use to refer to the deeply impoverished regions. The regions include Tibetan communities scattered across four provinces in western China, the southern part of the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region and three prefectures in Gansu, Sichuan and Yunnan provinces.

In a post that attracted 82,800 likes on Sina Weibo, The People's Daily said the developments were a milestone in Tibet's history, considering that almost 35 percent of Tibetan residents were poor only a decade ago.

"I work in Tibet," said one Weibo user. "I've heard many people from the older generations express their surprise at the tremendous changes that have taken place there in the recent past. The nation has made incredible input there."

Centenary goals

A short time after becoming chief of the Communist Party of China in late 2012, Xi Jinping ramped up efforts to achieve "Two 100s" goals, of which the most imminent was to establish a xiaokang shehui. In the following year, Xi was elected president.

To achieve xiaokang, Xi launched a nationwide campaign to eradicate absolute poverty, the threshold required for a society to boost relatively high living standards.

"It is a battle without smoke," said Liu Yongfu, during an annual gathering of officials in December in Beijing. Liu is director of the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development, the top poverty relief agency.

He said that the sweeping battle "has no bystanders", with almost all of society mobilized in a short time to do their share, based on their respective strengths. All of them aimed at marching into the long-awaited xiaokang era-east and west, rural and urban-on schedule, he added.

Nonprofits, research institutes, banks and even multinationals were also active contributors, offering low-interest loans and gene-editing crops that can survive extreme weather and soil conditions. Many of the programs were tailored for regions mired in poverty.

According to Liu's office, State-owned enterprises allotted 6 billion yuan in financial aid to impoverished regions in 2018 alone. Some 88,000 private businesses offered to be paired with more than 100,000 poverty-stricken villages, investing 75 billion yuan and immense effort to help foster local industries.

"The enthusiasm of private businesses for the task has far exceeded our expectations," said Wang Dayang, who oversees nongovernmental involvement in poverty reduction at the poverty alleviation office.

The payoff has proved it was worth the effort, and the progress in poverty reduction has stunned global observers.

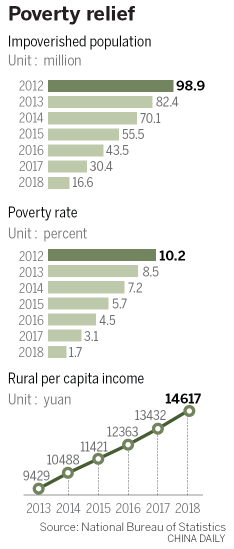

China's rural poor, which stood at almost 100 million in 2012, plummeted to 16.6 million by the end of 2018. The incidence of poverty nationwide fell from 10.2 percent to 1.7 percent during the seven-year period, making China a pioneer in reaching the Millennium Development Goals in 2015, which were set by the UN at the turn of the century.

Authorities estimate that another 10 million or more people will shake off poverty this year.

Targeted measures

China started tackling widespread rural poverty decades ago. In 1986, almost a decade after China decided to reform and open up its markets, Beijing created a cross-departmental office responsible for poverty reduction, which was the precursor of the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development.

In 2000, the central government launched a landmark program to aid development in vast, poverty-stricken western regions. This in turn expanded much-needed infrastructure in the inland areas and instilled momentum for growth.

But many remained impoverished in rural areas due to varied reasons that could not be solved by a one-size-fits-all approach.

In 2013, President Xi Jinping proposed the idea of a targeted poverty alleviation plan for the first time during an inspection tour of Shibadong village in Hunan province.

Under the targeted relief campaign, officials are forbidden from merely handing out relief funds without finding ways of attaining sustainable incomes.

Instead, they were asked to carry out a thorough assessment of their resources, environmental conditions and culture, and draw up tailored, efficient relief plans.

The plans vary from village to village in some of the most remote areas, and may cover a range of ethnic groups.

In the vast but sparsely populated Tibet, mass relocation programs were widely adopted in an attempt to boost the incomes of herding communities and better provide public service.

Nyima, who now lives in the Sanyou village that is a one-hour drive from Lhasa, is among hundreds of Tibetans who have recently cast off poverty after participating in a mass relocation program.

For years, Nyima, who like many Tibetans goes by one name, had struggled to feed her extended family of six by rotating crops such as highland barley, wheat and tomato on a small patch of land in an impoverished community on the outskirts of Lhasa.

To bring in extra cash, her husband, who is an unskilled worker, had to seek temporary, poorly paid laboring jobs in nearby towns.

The family's plight was worse in summer when surging rainfall caused frequent flash floods in her village which sits in a ravine. The damaging torrents washed away bridges, disrupted farming and jeopardized the safety of her son and daughter, who both walked kilometers along a worn path to the nearest school.

"Those were hard days," said the 54-year-old Nyima.

In 2016, she applied for a place in a mass relocation program that targeted needy farmers near Lhasa. Her family was given a two-story Tibetan-style house near a train station bustling with travelers from across China.

There, her family runs a milk tea house, which helped her escape poverty in 2017. "My son was admitted to Xiamen University last year, and we all have great expectations for him," she said.

Safety net for strugglers

Despite the progress, millions are still grappling with dire poverty, mostly scattered across the vast Three Areas and Three Prefectures outside Tibet-a mosaic of ethnic communities.

A report made by the Minister of Civil Affairs Li Jiheng at a recent legislative session shed light on the problems there. Li said among some 17.5 million impoverished recipients of State benefits in the Three Areas and Three Prefectures, 63.5 percent were seniors, minors, or people frail with disabilities or chronic diseases.

That had made it difficult for authorities to lift them out of poverty through conventional means, such as fostering local industries or developing tourism.

Basic living allowances and other State benefits are considered the last measures to be adopted in an effort to ward off the "Two Worries"-the lack of food and sufficient clothing.

The "Two Worries" is an euphemism for the income threshold where a household is deemed to have cast off the poverty label.

The report said China allocated 562 billion yuan in subsidies to help people in need from 2016 to 2019. The funds were used to help people in extreme poverty, orphans, the homeless and beggars, among others.

"We'll make concrete efforts to strengthen social relief work, to ensure that the bottom buffer works and that the poverty reduction battle will end in victory," he said.

- 'Cooperation is complementary'

- Worldwide manhunt nets 50th fugitive

- China-Japan meet seeks cooperation

- Agency ensuring natural gas supply

- Global manhunt sees China catch its 50th fugitive

- Call for 'Red Boat Spirit' a noble goal, official says

- China 'open to world' of foreign talent

- Free trade studies agreed on as Li meets with Canadian PM Trudeau

- Emojis on austerity rules from top anti-graft authority go viral

- Xi: All aboard internet express