Op-Ed Contributors

They deserve a city house as the new decade's gift

By He Bolin (China Daily)

Updated: 2009-12-31 07:51

|

Large Medium Small |

For more than four years, Li Xiaolan has been building subways in Beijing. But she doesn't have a feeling of belonging when she rides a subway train. The subway doesn't belong to her, nor does she belong to the city. Why? Because she is a migrant worker from a rural part of Sichuan province 2,500 km away.

There are at least 5 million people like her in Beijing alone - young workers recruited from distant rural areas who still have their homes where they were born. There are another 5 million like her in Shanghai. For more than two decades, all Chinese cities and townships have depended on these migrant workers for building their homes, running their assembly lines, and delivering all sorts of roadside services.

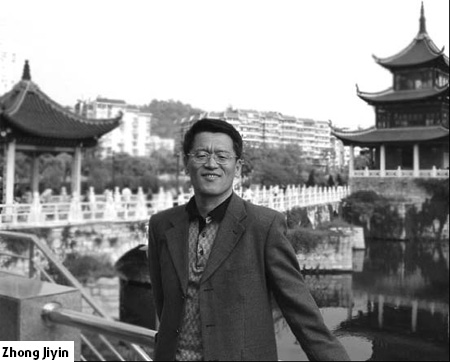

But as a new decade dawns, Zhong Jiyin, of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' Institute of Economics, says a new leaf is about to be turned in the lives of these young men and women (and there are 220 million of them, according to an official survey). They could earn the right to settle down in the cities they have built.

| ||||

In the next decade, the economist says, at least 250 million rural people will move home from villages to cities and townships. They will help enlarge the country's officially registered urban population from about 45 percent to more than 65 percent. Though it will take place in one country, it could be the largest urbanization campaign in world history.

Referring to the communiqu issued by the Communist Party of China's Central Committee after the economic conference earlier this month, Zhong says that at least the lifting of migration restrictions in small- and medium-sized cities can be expected to come soon.

Another turning point will be that urban development will no longer be synonymous with erecting larger and taller buildings, or what he calls "superficial prosperity." City officials will have to shift their focus to more humane aspects such as employment, social security, medical care, educational development, energy conservation and support to low-income housing plans. They have to help the new settlers and their families overcome the discriminations that remain against migrant workers.

"People ask where is China's domestic consumption. They will get their answer once these are in place," the economist says. "People wonder how can there be sustainable development. They no longer have to do so once we start doing these."

The hukou system was designed in the 1950s when the country's economy was weak and daily necessities were rationed in cities, and people's movement from rural to urban areas had to be restricted. Since the situation has improved drastically from those days, there is no reason to still follow that system. Although it has been in existence long enough to appear like something normal, the hukou system, in fact, has been a drag on the country's progress. It has stunted the growth both of domestic consumption and civil society, Zhong says.

We need change. The question is how. How should the new urban residence rules be made? Zhong believes in the principle of "the simpler, the better".

"In my opinion," he says, "too many rules would tantamount to another kind of refusal." Proof of continuous residence in a city for three years and a valid tax record should be enough for a migrant worker to earn his or her urban residential permit, he says.

For larger cities, the required work experience could be extended, say from three to five years. This will have a double effect: It will spread the new residents across small and big cities, preventing bigger ones from being overcrowded, and give the smaller ones the opportunity to grow faster.

But workers' choice will have to be considered, Zhong says. They should not be forced to give up their rural residential status - which is usually tied up to some land rights in their old villages.

The invisible hand of market mechanism can also play a role in maintaining a level of competition in the urban job market and, ideally, breaking down vested interests, particularly urban residents' preference for local government posts and public service jobs. The more skilled workers, irrespective of whether they are new or old residents, deserve higher posts and pay, the economist says.

More importantly, a fair and open market system is crucial for countering the monopoly of State-owned enterprises, and promoting private capital and small and medium-sized enterprises. The government can create only some new opportunities. It is the market and private investment that can offer the conditions for an overall flourishing urban job market. The government cannot be expected to create a prosperous city single-handedly. It will have to learn to build the local economy by attracting more resources from outside.

A more appropriate role for the government to play would be to prescribe and reinforce the regulations to assure workers' equal rights, Zhong says. Now, however, not many Chinese cities seem to attach due value to private investment. All they have been good at, especially in this year of global recession, is jacking up GDP by taking up massive infrastructure projects, such as new subways and bridges.

No city can keep adding subways and bridges forever, without attracting more people to use them. Only by channeling a steady flow of private capital into the economy can growth become a sustainable cause, the economist says.

But now that China has 118 cities with a population of more than 1 million each, isn't it a fearful task to help an additional 250 million people floating in its urban areas to find jobs and homes? Zhong says there will always be some negative side effects, and most likely the rich and poor divide could widen in large cities.

He argues that this is still less of a problem compared with the existing rich-poor income gap created by a legally static urban-rural segregation. By combining better protection of civil rights with a fair and open market, private capital may help the new settlers seek upward mobility and thus narrow the rich-poor income gap.

For urban people who are losing out in the job market, the social security umbrella should always be available to cover their very basic needs, just as many government agencies are trying to do both at central and local levels.

Zhong says the most important help economic and social mobility can get is from education.

Equality in public education should be the key for the new settlers and their families to better fit into the urban social networks.

In practice, that can be a substantial reform, considering that for a hukou-less child to go to a local primary school in Beijing, his parents would have to pay up to 30,000 yuan if not more.

For a worker in subway projects like Li Xiaolan, that amount would be more than a year's income. So the change, hopefully coming with the New Year, would be liberation indeed.

(China Daily 12/31/2009 page9)